Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects, my recipe development journal. Thank you so much for being here!

Today we are jumping into the world of airy sponge cakes - fortunately there’s a very soft and squishy landing. I’m talking chiffon, genoise, Jpanese cheesecake, angel food cake and more. You’ll get the meet the whole family and see what makes these cakes rise, fall and everything in between.

Over on KP+, I’m sharing my ultimate summer cake recipe which blends two of today’s subjects: A ricotta chiffon cheesecake with a selection of the most delicious macerated fruits. Click here to make it.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter and get access to an amazing community, extra content, the full archive, and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come n join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

Something in the air…

In the summer, there’s no combination I love more than a sponge simply paired with fruit. But there’s a bit of a deceptive word in there. Sponges are ANYTHING but simple. That doesn’t mean they are hard to make, necessarily… it’s just that ‘sponge’ can mean a LOT of things. There’s truly a world of sponge cakes out there, ready for the taking.

When you think of a sponge cake, what do you imagine? I expect it’s slightly different for all of us. I imagine a light, pale sponge that bounces or wobbles when gently tapped with a fork. It’s a sponge with a thin crust that squishes as you try to take off its nose, eventually giving in. That’s the thing about recipe development and baking - how fun is it that we get to imagine something and then walk to our kitchens and actually create it? Welcome to Kitchen Projects Guide to Airy Sponge Cakes!

But before we can conjure up a cake, we need to know where to begin. And let me tell you - sponges are not created equal. I mean that, literally. Each one is unique in the family tree of sponge cakes - and it’s seriously sprawling. Traditionally, ‘sponge’ refers to cakes leavened solely by the expansion of air trapped by whisking eggs, known as ‘foams’. This name reflected the similarity between a cake and a natural sea sponge, in appearance and texture.

A sponge family, divided

To begin, I will brutally divide the world of sponge cakes into two clear branches: The ‘dense and buttery’ and the ‘light and airy’. You can also think of these as ‘BBP’ and “ABP” - Before Baking Powder and After Baking Powder. Let’s jump in.

Dense and buttery sponges, aka “ABP.”

Dense, buttery sponge cakes, firmly in the “ABP” club, tend to be leavened with a combination of creamed/butter sugar and chemical raising agents. These are often the cakes of our childhood - think of your typical Victoria sponge. These cakes emerged in the early 20th century thanks to the advent of baking powder, an invention by Alfred Bird (it’s actually a very romantic story, read it here!) Fat, lethal to light and airy egg foams, could now be added in higher quantities. You can read more about this type of cake and the recipe for my ultimate Victoria Sponge here.

Light and airy sponges, aka “BBP.”

Let’s take it back to before all this butter, before Alfred Bird and his baking powder, to the original sponge cake, the world of airy sponges. For these cakes, which include genoise, chiffon, and angel food cake, to name just a few, it’s all about air.

These air bubbles, trapped in our cake batters (thanks to eggs!), expand when heated. The cake batter, which is at first flexible, will expand with it, causing the cake to rise. As the cake continues to cook, the egg proteins coagulate and starches set in place, setting the final form of the cake. Some of these airy cakes are so fragile that they need to be cooled upside down to prevent the cake from collapsing and forming dense, gluey streaks inside the cake.

Where airy cakes begin to deviate from each other is the way the ingredients are balanced and, crucially, the treatment of the eggs. I whipped up (pun intended) some of the most famous air-leavened cakes to learn more about how they work.

Eggs and Air

I’m not sure whether air can exactly be classed as an ingredient, but in foam cakes, it would be at the top of the call sheet. But it doesn't just magically appear in our cakes. We need to work to get it in there. If you were to rank the ‘big four’ baking ingredients from BEST to WORST at incorporating air, there is one clear winner: Eggs.

The whole egg, white and yolk have different air-holding abilities. Whole eggs will increase 5x in volume, yolks will increase around 3x in volume, and egg whites will increase 6-8x in volume. So what happens when we whisk eggs?

When agitated with a whisk, the proteins in eggs begin to unfurl and bond. As these bonds form, air bubbles are trapped within, and the volume increases. The unfurling and joining of these bonds are actually known as coagulation, which is why the egg white changes from translucent to opaque. I associate coagulation with heat, but whipping eggs up is another way of looking at coagulation since the proteins are bonding with each other but just in a different way. The coagulation is permanent in both cases, as they cannot return to their original form.

As the foam forms, we can stabilise it by adding sugar. As the sugar dissolves, its hygroscopic nature draws water from the egg whites, forming a thick syrup. This syrup becomes trapped within the strongly bonded protein network and, as a result, coats the air bubbles. This makes it hard for the bubbles to merge or the air to escape, so the foam stabilises.

When you whisk egg whites alone, the foam begins as a floppy mixture but will slowly make its way through soft, medium and then stiff peaks. For whole eggs, owing to the presence of yolk, the foam will never become stiff - it will remain shiny and flexible.

It should be noted that if left, the foam begins to set, turning from fluid and shiny to chunky. This is because egg proteins will continue to bond with each other even after the agitation has stopped, making your meringue hard to combine into another mixture.

The foam cake family

For today’s newsletter, we’ll compare some of the big heavy hitters in the foam cake world. This cast of characters can be subdivided into two main categories: Whole eggs and separated eggs. These foams provide the main backbone of these airy cakes and are strong but not infallible. They can be destroyed in several ways: Poor handling of the foam while you fold it into the other ingredients may result in dramatic air loss. Leaving a foam to sit for too long before incorporating it can turn it from malleable and flexible to dry and separated.

Whisked whole eggs

On team ‘whole eggs’ we have:

Genoise is a classic light sponge made by whisking whole eggs with sugar then carefully folding in the ingredients - read the newsletter deep dive ft. Chef Ayako here.

This is where I also learnt about our second whole egg teammate, the Japanese “Kasutera”, aka Castella cake. Both cakes use whole eggs whipped until a thick foam forms, but the final texture is different. As I understand it, the main difference between the genoise and the Japanese Castella is the flour: The typical genoise should be ‘fuwa fuwa’, aka light and fluffy and use low protein flour, whilst Castella cake should be ‘wagashi’, which is more traditional to the Japanese sweet tradition and should be closer to chewier and stickier, achieved by using higher protein flour, like bread flour. This results in a more dense texture. Japanese Castella also uses honey for flavour and is finished with sugar syrup for extra moisture.

Where did Castella come from? I love the story of Japanese cuisine because it has so enthusiastically incorporated dishes from other cultures into its own unique point of view. You can trace some of its most famous dishes - Tempura! Curry! - across the world. And to tell the story of Castella, we can look to Portugal.

The arrival of Portuguese traders and missionaries in the 16th century in Japan was also the arrival of food customs still enjoyed today, now known as ‘Nanban’. Nanban is an old term that translates as ‘Southern barbarian’. Nanban cuisine, reflecting the Portuguese palette, had a lot more oil, sugar and spices. Nanban cuisine includes dishes like Tempura and Castella cake, which is a direct relation to Pão de Ló, the - sometimes gooey but always delicious - sponge cake from Portugal.

Whisked egg whites

On team FLUFFY EGG WHITES aka cakes that are leavened by a meringue base we have:

Taiwanese Castella

Following where we left off on whole eggs, let’s begin with a lesser-known cake (at least in the West), the Taiwanese Castella. The castella cake, which uses whipped egg whites, was introduced to Taiwan during the Japanese occupation (1896-1945). It has a more custardy, wobbly and moist texture. This week was the first time I’d made these - it’s a very popular cake on YouTube, so shout out to Kitchen Princess Bamboo and Emojoie for their helpful videos.

Angel Food Cake

Next up, we have the angel food cake. Notably, this cake does away with yolks and fat, making it completely fatless. It’s pretty much just a pavlova with extra flour, making it squishy rather than crisp. Angel Food Cake is a distinctly American invention and can be traced back to the Boston Cooking School Book published in 1884.Chiffon Cake

Chiffon cake is another distinct - and recent - American invention. Created by an Insurance agent Harry Baker in 1927, the chiffon took the blueprints of the angel food cake and added the yolks back in, along with more fat in the form of oil. It sometimes has a raising agent in, too. Adding fat makes the chiffon a squishy, tender and moist cake.

Japanese Cheesecake

If you’re not familiar with Japanese cheesecake, welcome to the club! I’m pretty new to it, too. I have YouTube to thank for all the videos (I watched a LOT - shout out to Nino’s Kitchen and Yummy Yummy). If I had to put it in context, it’s like a Taiwanese Castella cake made with cream cheese. It’s souffle’d, light and airy with a tearable, moist texture. Baked in a water bath and incredibly wobbly whilst warm, it’s utterly hypnotising. Made by melting cream cheese and butter, then folding in whipped meringue. Baked in a water bath, these cheesecakes rise in the oven and fall as they cool but retain a lightness you wouldn’t necessarily expect from something baked.

Separately whisked eggs

For one more outlier for the tests, I decided to try a hybrid sponge that bridged the gap between the richer sponge cakes with raising agents but also lightened with eggs, which are separated and whisked separately to foam before being folded together. It has a higher proportion of flour than most foam cakes - this means it has quite a lot of body but is still pleasantly squishy. I was VERY happy with this cake. I’ll share the recipe at some point here on the newsletter.

A note on a separated egg Genoise sponge

Although I haven’t included it in the main line-up photos, I did compare the mixing method of a genoise sponge. I made one classic (whole eggs with sugar) and one where I separated the eggs and whisked the white and yolk separately with half the sugar then combined together. The verdict? The separated egg cake was good, but not better than the whole egg cake (it even came out slightly shorter), and you had to do more washing up. It was also harder to work with. However, since the whole egg version requires a stand mixer with several speeds, I’d favour making the separated egg version if I only had a hand mixer. So, to better understand foam cakes, let's talk through each ingredient and its role and compare each cake.

On KP+ today

Over on KP+ today I have the delight of sharing a hybrid of these foam cakes - my Ricotta Chiffon Cheesecake as well as some of my favourite macerated fruit combinations. It’s so light and airy, spiked with lemon and vanilla:

The ‘right’ meringue

Depending on your recipe, it is advantageous to whisk your eggs to different stages.

As Chef Ayako taught me in the genoise edition, a prolonged, three-stage mixing process is the secret to a properly stable foam. We can encourage as much air as possible into the eggs by starting at high speed then slowly reducing the speed and mixing for a prolonged period. This subdivides the large, erratic bubbles into small, strong and stable bubbles without affecting the volume. At the end of mixing, there should be no bubbles visible. These tiny air pockets are much better at sustaining through the folding process.

Most meringue-based recipes will ask for stiff peaks when a beater lifted out of a mixing bowl boasts a pointy meringue crown. Angel food cake is the outlier - according to Stella Park’s recipe, the meringue should gently run off the beaters but be firm enough to form soft dollops. And I see the point here - very stiff meringue is VERY difficult to fold into the other ingredients. If your meringue is so strong that you have to fight to get it fully incorporated, you’ll deflate it. Not so fun. In my experience this week, it’s better to err on the side of slightly under-whipped and still flexible and tender.

Taking inspiration from the genoise mixing process, it’s sensible to whip your egg whites for longer and slower to create more stable, smaller bubbles. Although you can whip egg whites and sugar to a stiff meringue in a stand mixer in less than 2 minutes on high speed, I got better results when I whisked my eggs on high speed for 30 seconds til foamy, then added the sugar slowly and then reduced the speed to medium and whisked for 6-8 minutes.

Flour

Flour is usually the heart of baked goods, providing structure through gluten and starch. Though gluten often gets all the credit for being the scaffold of our bakes, we really owe a lot to starch gelatinisation. This is when flour absorbs water and swells, creating body and texture. When baked, the starch structure and proteins (gluten) are set in place, providing structure. Because flour ‘hardens’ as it bakes, it is known as a ‘toughener.’

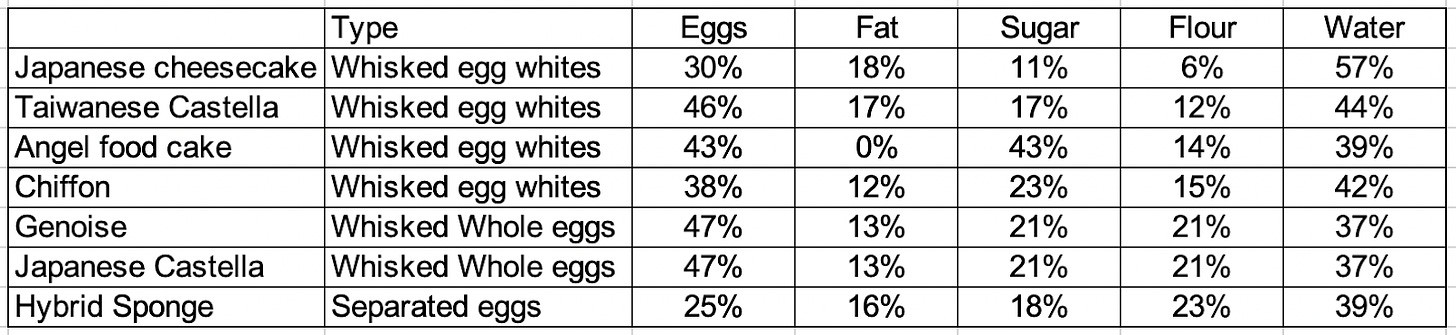

For airy foam cakes, flour does play a role, but it takes more of a back seat. Compared to a butter-rich cake with some 25% overall flour, the typical foam cakes I made ranged from 21% flour to a tiny 6% flour.

When a flour quantity is as low as 6%, the role is likely more to do with stabilising than providing structure. Because flour is very good at absorbing and binding water firmly through gelatinisation, a little bit can help prevent disasters like weeping or excess moisture in the final bake.

The cakes with the most flour - the hybrid sponge (23%), genoise (21%) and Japanese castella (21%) are the most familiar in texture - they are by far the driest (that sounds bad, but what I mean is, it doesn’t have a crumb that crackles with moisture and air when pressed) and have a sensible amount of stability. And, intriguingly, the Japanese Castella made from bread flour was the shortest of the bunch. These drier foam cakes are the best candidates for building layer cakes. The other candidate for layer cakes is definitely the angel food cake. What it lacks in flour, it makes up for in eggs! Sponge heaven! Let’s move on.

Eggs

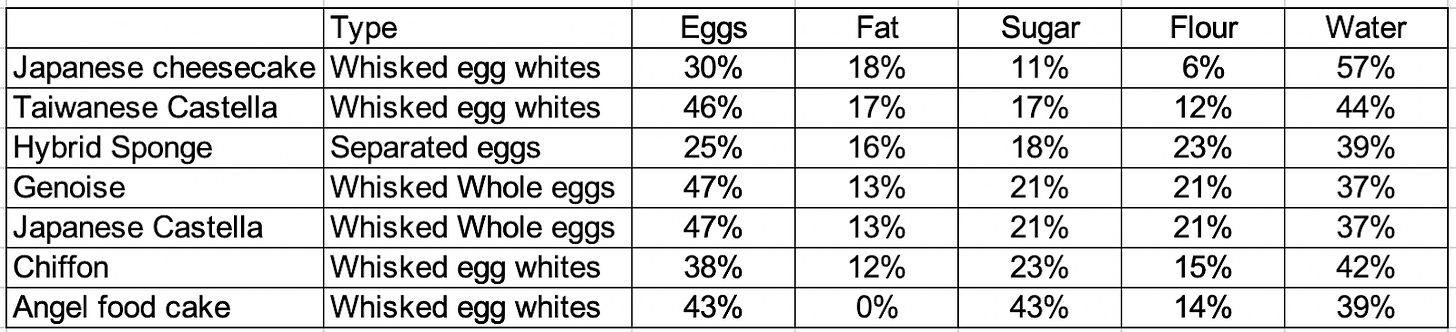

Like flour, eggs harden (i.e. coagulate) when baked. This means they are ALSO known as tougheners because they structure the final bake. It’s this twofold talent of being 1) very good at capturing air and 2) the ability to harden and set when heated that gives foam cakes the unique light texture. As a result, eggs tend to be the dominating ingredient:

Unsurprisingly, the cake with the least eggs also has the most flour - go figure! You see, baking is all about balancing the tension between things that give structure (like flour and eggs) and things that tenderise. Playing around with these ratios helps us achieve a cake that is either crispy, fluffy, chewy or moist. Or a combination.

The cakes that use whisked whole eggs have the largest amount of eggs - this is likely because the amount of air we can whisk into whole eggs is lower than whites, meaning we need a relatively larger amount of whole eggs to achieve a good rise.

For the hybrid sponge, I whisked the yolks and whites separately. Although I’ve never seen a huge benefit of whisking yolks and whites individually, in the case of a higher proportion of flour cakes, it is useful to increase the base's volume. The expanded yolks + the fat + the liquid makes a much more flexible paste, again making space for the real star of the show, the meringue.

Sugar

Sugar is a famous tenderiser in baking. This is why high-sugar bakes like cookies and brownies tend to be gooey in the middle. Sugar tenderises because of its hygroscopic nature - it holds onto water and attracts moisture, helping baked goods stay tender. Its role in foam cakes, however, is to stabilise the foams as outlined earlier.

Meringue ratios, i.e. how much sugar per egg white, is an intriguing topic I outlined a few years ago in my Tres Leches Cake KP. It can vary from 1:1 to 0.5:1 to 2:1. To sum it up, the more sugar, the more dense the meringue. A denser meringue will fold less easily into other ingredients simply because it has more body - you would have to work very hard to break down such a stiff meringue.

As well as this, a meringue made with a lot of sugar means all of the water is strongly occupied. In cakes, we want some of the water in egg whites to help expand and rise the cake alongside the air bubbles. So, foam cakes tend to use meringues with a lower ratio of sugar to egg white than a standalone meringue like pavlova. Let’s have a look:

The highest egg white to sugar ratio is the angel food cake, which is a 1:1 ratio. The lowest is the Japanese cheesecake - this makes sense. There is a lot of sugar and sweetness in the cream cheese and milk in the recipe (lactose, I love you!), and a tender meringue is incorporated easily into the recipe.

Fat

Famously tenderising, both the type of fat and the amount of fat makes a difference in these cakes. Solid fat, like butter, tends to result in a more flavourful but drier cake, while cakes made with oil are less flavourful but more tender. So how does it do it? Fat coats the other ingredients, preventing them from doing useful, structure-building things like forming gluten. It also prevents foams from forming properly, making it a tricky beast in foam cakes. As a result, most foam cakes carefully fold fat in right at the end, keeping it away from the fragile foams for as long as possible.

Let’s start with what a cake is like without fat: It’s not as though the angel food cake lacks tenderisers - it is full of sugar - which means it is pleasantly squishy and fluffy, but the lack of fat means it lacks flavour. It probably gets the prize for most squishy but also for least interesting.

Though oil doesn’t actually hydrate things, it can give the effect of being more moist because it remains a liquid once it cools down, compared to butter which rehardens. This is one of the reasons why chiffon cakes tend to be more bouncy and squishy than genoise. Intriguingly, if you compare the combined amounts of tenderisers in the chiffon, hybrid and genoise (sugar + fat) - they are the same! So, the foam cakes that lack sugar may make up for it in fat, and vice versa.

The Japanese cheesecake gets much of its fat from the cream cheese, compared to the other recipes, which look like butter or oil.

Moisture

The final intriguing factor for the foam cakes was comparing the moisture. Moisture comes from LOTS of places in baked goods - you’ve got the obvious culprits like milk, but we also need to consider the water in eggs and butter. The water, or moisture, in a recipe will define the final texture (soft! Wet in a good way) and contribute to the rise during the bake. A combination of air + steam (from water in the ingredients) makes for a lofty cake.

We also need to be aware of how we will capture all that water - this means trapping it with the help of flour (gelatinisation), occupying it with sugar or setting it with eggs (coagulation). But ultimately, if the moisture in the cakes is low, you can really taste it when you eat it. The cakes with the lowest moisture % are fluffy and tender but aren’t moist. This is why these cakes are often paired with cream or syrups, while chiffon, Taiwanese castella or Japanese cheesecake can be enjoyed independently.

The baking

Another way these foam cakes vary is in how they are baked. Some require a water bath, whilst others can be baked at higher temperatures. Let’s consider the difference in baking temperatures:

You’ll notice here that cakes made with whisked whole eggs can withstand higher, more aggressive baking temperatures than eggs that rely on meringue (egg white only) bases. This is likely due to the relative amount of air in the mixtures. Because egg whites can capture so much more air than whole eggs or yolks, cakes made with whites are more susceptible to rapid expansion and rupturing. When we bake a cake, we need to balance expansion and setting - if the flour and eggs (especially on the top!) are set before the middle has had a chance to cook, the cake will split open.

But what about angel food cakes? Usually served top down, it doesn’t seem to be as much of a problem for bakers - perhaps the huge quantity of meringue makes splitting seem inevitable? Since the angel food cake batter lacks inherent flavour, the higher baking temp helps give a favourable crust which adds to the eating experience.

The deal with water baths

Waterbath is a cooking method that has you bake your cake partially submerged in boiling water to help create a more gentle cooking environment. How does it do this? Well, let me tell you: Heat exchange, which happens when you put something in the oven, is quite different between water and your cheesecake vs air and your cheesecake. The water absorbs some of the heat from the oven, regulating the temperature, resulting in a more gentle and even bake. As well as this, the issue of the edges of a cake (which are usually exposed to aggressive oven heat) baking before the middle is ready is circumvented - the edges stay very moist and tender and don’t undergo Maillard reactions, aka do not brown.

Cooling

As I mentioned, some foam cakes are so fragile that they must be cooled upside down. These are the cakes with the least flour - the lack of hardening starch in the chiffon and angel food cake means they are particularly susceptible to collapsing without this extra step. Though Japanese cheesecake and Castella cake have lower flour than these two, you couldn’t possibly cool them upside down - the centre is so fragile and eggy it would fall out in a pile of slosh. Many chiffon cake pans come with little feet, so you can turn them upside down easily, but I usually make a trio of cans and balance the cake dangerously on it.

Colour

The varying ingredients also have an effect on the visual appeal of the cake. The angel food cake, with its very high sugar ratio, forms a golden crust on the top, which is quite fragile. The Japanese castella, which uses honey, has the darkest crust. This is because honey has a lot of fructose. The other dark crust belongs to the Japanese cheesecake - this is because of the high amount of milk proteins in the cheesecake will undergo rapid browning in the oven.

Ready to bake?

So, there we have it. An introduction to all of the foam cake family. There are a LOT of amazing foam cake recipes out there (please go down the Castella cake and Japanese cheesecake youtube rabbit hole - it’s fun here!)

I plan to share my take on these classics over the next few months, but let’s start with something I developed especially from my learnings this week: The love child of a chiffon x Japanese cheesecake ft ricotta and vanilla. It’s an airy, moist dream cake with a charmingly wrinkled top that could not be more delicious with simply macerated fruit. Get the recipe for the cake, plus recipes for my favourite macerate fruit combos (Gooseberry elderflower! Cherry balsamic! Peach fig leaf! Blueberry Vanilla lemon!) here:

Beyond that, there are plenty of foam cake recipes in the newsletter archive. Here’s a few to get you started: Genoise sponge / Strawberry Shortcake, Helen Goh’s Pandan Chiffon cake, Pão de Ló, Honey and Blackberry Toasted flour Genoise, Mimosa Cake and Brown butter / Walnut coffee genoise.

So helpful. Love seeing all the comparisons!

omg, that jiggly cake!