Kitchen Project #107: All about Fig Leaves

All hail the herbaceous dream leaf! aka FIG LEAF PALLOOZA!

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects, my recipe development journal. Thank you so much for being here!

Today we are doing an ingredient spotlight on one of my favourites: Fig Leaves! If you don’t know them, get ready to fall in love with their herbaceous, nutty scent. I’ll talk you through all the basics and share my recipes for making your own syrup and oils.

Over on KP+, I’ve shared a series of fig leaf recipes. I kind of couldn’t control myself this week. From Fig Leaf Milk Jam to roll cake, i’m also thrilled that superstar Marie Havnø Frank is sharing her recipe for Fig Leaf Ice Cream. Heaven. Click here check out the index.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter and get access to an amazing community, extra content, the full archive, and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come n join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

Go FIG or go home!*

*Credit & all my thanks to Indira for providing the perfect title to this newsletter

I’ll be honest - I’m not a natural forager. It’s not that I don’t enjoy the fruits of foraging’s labour. It’s that I forget to do it. In early June, I walk past an elderflower tree and always think I’ll return later to pick the flowers but I often remember too late. I’ll notice a patch of wild garlic in Spring, but I’ll fail to return before it’s been spoiled. I might spot a mushroom on a wooded walk and make a note to google it to check its toxicity, but alas… it never comes to pass.

But this year, I had no choice but to pick fig leaves - forgetting was simply not an option. The thunderstormy summer weather in London beat down upon the front garden fig trees, and the leaves responded in a resounding, unignorable chorus. The scent was calling to me.

Fig Trees have an enduring presence in both food and art. Native to the Mediterranean region (and thought to have originated in Western Asia and the Middle East), trees also grow in more tepid climates, like here in the UK. The trees here produce fruit but rarely ripen to their full jammy potential, like in warmer countries (FYI, unripe green figs can be used to make syrups and condiments but aren’t great for eating raw). Even so, the leaves have a lot to give.

Even if you’ve never tried the flavour of fig leaf, you’ll know that figs and their leaves have serious metaphorical meaning. The fruits are famously sensual (I blushed when reading ‘Figs’ by DH Lawrence! Google at your own risk!), yet expertly placed fig leaves have long been used to protect modesty in art. What’s that about? Well, this practice is modelled after Adam and Eve’s example in the Bible; You see, after they took fruit from the forbidden tree, they suddenly realise that they have been naked all along and - reacting from a place of shame - sew fig leaves together to cover up.

But before this mass representation, Figs were the sign of good times only! In Greek mythology, they strongly associate with Dionysus, the God of wine and revelry, and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and fertility. The Romans adopted and expanded on this fig fandom, believing that Figs were a gift from the Gods (Dionysus was known as Bacchus in Roman lore). The fruits were given as offerings and enjoyed at the Bacchanalia, the annual festival famed for its uninhibited, debauched celebrations. If you’ve ever read Donna Tartt’s ‘The Secret History’, you’ll know what I’m talking about.

When the Roman Empire converted to Christianity in 313AD, so began the censoring of art. Statues were amended or adjusted, often turning to fig leaves for modesty. Reading about the mediaeval censorship campaign is an extraordinary rabbit hole to go down - the duality of the fig and its leaf is a wonderful lesson in symbolism. But this newsletter is about food. So let’s get back on track, shall we?

The fig leaf flavour

The fig leaf has a curious flavour - it’s familiar but in that ‘can't quite put your finger in it’ way. It's subtly intoxicating with notes of herbaceous green vanilla, echoes of fig, and a base nuttiness of coconut. Green is an intriguing flavour profile - there are definitely degrees of it in cooking, ranging from ‘vegetal’ and ‘grassy’ (think: biting into a stem) to ‘fresh’ and even acidic and bright. In fig leaves, the greenness has a verdant fragrance bordering on sweetness. It’s this undercurrent of unripe fruit, budding with promise, that charms me so much.

Once you’ve fallen in love with fig leaves, it’s good to know there are many ways to enjoy the flavour. It’s one of those ingredients you can really lean into: From infusing into syrups or dairy to blitzing into powder to blending into oil, to using them as protective wrappers, you can deploy the flavour into all your favourite dishes. I will say up front that fig leaves are no good to eat as is - they are far too fibrous. That means we’re left to figure out how to extract and enjoy the flavour.

So, in today's newsletter, we’ll dive into the world of fig leaves together, From how to find them and best foraging practices plus all the ways you can use them: Welcome to FIG LEAF PALOOZA.

Fig leaves and where to find them

If you’re new to fig leaves, you may be happy to know that a little goes a long way, just five or six will likely be enough for any recipe. But picking the right leaves is still important. There is debate about which leaves are the best, with recipes often citing young leaves… but is that true? Should we even bother with the more mature leaves? I decided to put the question to two fig leaf experts (Yes, that is a thing!) to find out what’s what. For this week’s newsletter, I was delighted to speak to two dedicated, life-long foragers: John the Poacher and Wildpicker.

John Cook, aka John the poacher, is a trained chef and London-based forager who procures all things wild for best for restaurants and producers across the city. Since moving to Hackney at 7, he has been foraging the area for over three decades - he knows all the spots and where to look. As well as leading his foraging walks, John - a trained chef - hosts pop-ups, from cocktail events to foraged supper clubs. You can book into his walks and find out more by following his Instagram @Johnthepoacher.

Marc, aka Wildpicker, grew up foraging on the beaches of the Isle of Wight but is now based in Wiltshire, South West England. He started foraging more seriously “about 25 years ago”, collecting for his wife and friends. When a chef friend held a fundraising auction, Marc was encouraged to offer a foraging walk as one of the prizes - he enjoyed the teaching experience so much that he began offering walks on a regular basis. You can now book into one of his walks on several beautiful estates across the South West (or book him for a private lesson!).

How to forage fig leaves

There are a few big questions when it comes to foraging. The first is usually ‘When?’ and the second is ‘How?!’ (and when you might ask Where?) Although I typically associate fig leaves with summer flavour profiles, John explains that you can forage the leaves “Any time really - except the dead of winter.” which bodes well for all of our future endeavours as fig leaf fanatics.

There is much debate about whether the age of the leaf should be taken into account. Marc explains that he prefers to pick “relatively young leaves”, which can be found “early in the season” (typically June) when the trees are still putting energy into making leaves before turning their attention to the fruit.

So, why do some fig trees seem so heavily scented whilst others hardly give any clue of the intoxicating scent and flavour within? John theorised that it could be “down to the insects on the leaves.” Left to work and nibble on the plants, insects can “expose the scents. If you walk past a tree and it's smelly - stop and look. There’s probably a lot of bite marks.” A good reminder, he continues, to “leave some for them.”

Does that mean we should avoid the less-scented trees? According to John, No - “They all taste the same.” he reassures me.

Marc offers another explanation for my scent conundrum. “It’s probably different weather conditions. Effectively you’re smelling the oils in the leaves when they are being baked by the sun. I’ve never known any fig leaves that don’t have the scent of coconutty aroma once they've been heated.”

When picking the leaves, it’s worth mentioning that the Fig leaves exude a white sap (“latex”) when torn or picked. Marc explains that this sap “contains a phototoxic chemical which can cause skin irritation”. But don’t worry - it’s heat soluble, so fig leaves are safe to eat once infused or cooked. While Marc tells me he has never experienced any strong adverse effects from the sap, you should consider wearing gloves when foraging for the leaves if you have sensitive skin. “Be careful of the milk. It can cause blisters”, John concurs.

When it comes to size, John doesn’t worry too much about that. “The only difference between the young and old,” he tells me, “is the usefulness. Larger leaves are good for wrapping fish.” And Marc reminds me that “The really baby ones aren’t worth picking”, and we should only take the leaves “once they are the size of your hand, and upwards.” Of course, both warn against picking leaves that are yellowing or wilting. “And make sure you avoid bird poo!” says Marc.

Removing the leaves is easy. I always take scissors with me but John tells me you can remove the leaves easily without them. “Hold them by the stem or leaf and tear them off”, he explains, “If you try and pull them towards you, it won’t work, so fold them back on themselves.”

Before you pick your leaves, be aware of the rules around foraging. As Marc tells me, “You are very unlikely to find a fig tree in a public space”, so access must be considered. In the UK, Marc explains that we “have a common law right to forage the four F’s: Fruit, Foliage, Flowers and Fungi.”

This means that “On public land, you have that right. But 99.9% of fig trees are going to be in gardens.” so permission must be sought. But what if they are overhanging a wall? “Even though you are in a public walkway”, Marc explains, “You don’t have the legal right to forage from those trees. If you're picking from an area that is overhanging the pavement, the owner may even be happy.” But strictly, this does mean you are legally supposed to give the leaves back to them.

Once you’ve picked your leaves, they don’t have to be used immediately. According to Marc, leaves will last “a week or two in the vegetable tray in the fridge.”

When you are ready to use them, Marc and John are filled with inspiration and ideas: “Fig leaf ice cream is probably the best ice cream ever,” says Marc. “I usually post every year about it, just to remind people it's out there.” For Marc, the leaves “definitely have to be toasted.” What is the best way to do this? “Just toast them in a dry pan. But if you want it really charred you can go under the grill. The flavour is still similar; it doesn’t drastically change but adds another layer of complexity.” As well as a direct infusion, Marc suggests drying the leaves and blitzing them to a powder which can be later introduced into ice creams, giving them a vibrant green hue.

John suggests fig leaves work well “in a quick pickle for vegetables, which are great for Bahn mi,” as well as “custards, creme brulee and Rice pudding!” and uses both the leaves and the stems for the full flavour. He also likes to tear them up and seal them in a jar with vodka, producing “A figgy coconut malibu.” How good does that sound? Well, it doesn’t end there. John tells me, “If you do that, then you can go and collect pineapple weeds. And then you can make a foraged pina colada.”

Though there’s plenty of mileage in my fig leaf fascination, I did ask for any other leaves we should be looking out for? “There’s loads!” says Marc. “All the members of the raspberry family, blackberries, redcurrants have great aroma. Lots of people make them into tea but you could make syrups.” So, here it is, your official reminder not to overlook the leaves.

Follow John the Poacher on Instagram to find out the latest availability for his foraging walks and to keep up to date with his events. John hosts walks in London as well as coastal foraging on Leigh-on-Sea.

Follow Marc ‘Wildpicker’ on Instagram for his latest finds and to learn more about his foraging courses and private lessons. Contact him and see availability via his website www.wildpicker.co.uk

Where to find them

So, now we know how to procure fig leaves… where to find them? As mentioned above, fig leaves tend to be in private gardens. Best thing to do is ask around your friends and neighbours. If you aren’t sure how to get in touch, I had great results posting on Nextdoor, the neighbourhood community app. A few of my neighbours were more than happy to help!

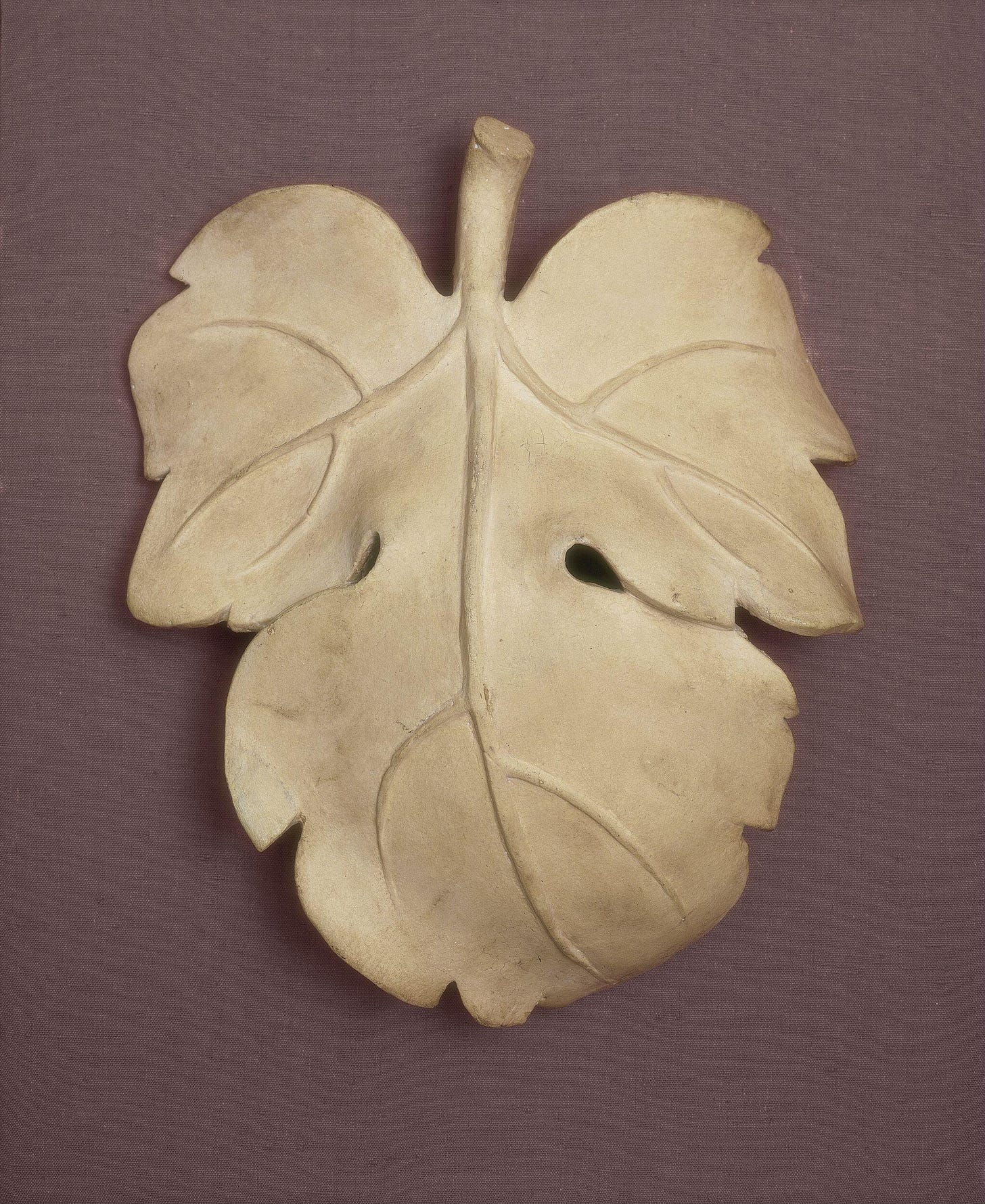

The deal with the size

I’m sure it won't surprise you to know that I take serious umbrage with any recipe that asks for a quantity of an ingredient rather than weight in grams. Especially when the ingredient in question, like a fig leaf, can vary in size. So how big is a fig leaf? I picked what (in my opinion) were small, medium and large leaves and weighed them.

Small comes in at 2g, Medium at 4g, Large at 8-9g. Although this is a pretty inaccurate way to measure it, it’s a good place to start for converting any recipes you see online that ask for a number of leaves rather than giving you a steer on weight. Remember, the stems are heavier than the leaves, so keeping long stems on will have an impact. Fortunately, the stems carry a lot of flavour, too, so you won’t be missing out.

SO, you’ve got your leaves… so how do we use them? Let me run you through the options.

Infusions

The most popular way to enjoy the flavour of fig leaves is through infusions. From adding a fig leaf to your rice as it simmers and steams (thank you, Tash @tashmillar, for that recommendation) to making ice cream, there are many ways to enjoy the fragrance.

Particularly potent, you don’t need a lot of leaves to benefit from the flavour. But before we get on how to use them, there is one question we need to address first, though:

To toast, or not to toast?

As I understand it, the flavour of the fig leaf will come out once heated as the oil releases. You can achieve this by toasting the leaves briefly in a dry pan or in a low oven (120/130c for 15 minutes, but watch it, or as Copenhagen-based pastry chef superstar Marie Havnø Frank suggests, 50c for 2 hours). As you toast the leaves, you’ll notice an intoxicating scent filling the air. Welcome to fig leaf land. It’s good here.

However, if you are heating your fig leaves in a recipe anyway, i.e., infusing them into hot milk, you’ll benefit from the flavour either way. All that matters is that the fig leaves get hot. Toasting them will add another layer of complexity, especially since (as Wildpicker suggested) a few charred notes can go a long way, but it’s okay to skip this step if you want to. Untoasted leaves have slightly more ‘green’ notes, whilst toasted leaves have more coconut notes, though, to be honest, it’s very similar.

There is another benefit to toasting the leaves; Fig leaf sap contains the enzyme ‘ficin’, which can coagulate milk. Though it doesn’t always prevent it from happening, toasting the fig leaves can neutralise the enzymatic activity. This isn’t an issue in sugar syrups, nor does it make or break a custard (the curdling isn’t extreme and won’t notice once passed through a sieve), but it’s worth knowing.

Liquid infusions

One of the simplest and most effective ways to get fig leaf flavour into your life is via liquid infusions. This is usually in liquid dairy (like milk or cream) or water/sugar syrups.

When it comes to ways to ingest fig leaf, ice cream is hard to top. I will warn you, though - once you try fig leaf ice cream, it’s likely to shoot to the top of your favourite flavours. That means you need to be prepared to make yourself a constant supply since I’ve never seen it sold commercially anywhere. For syrups, you can use it to douse layer cakes, make cocktails, add to ice tea (my recipe for peach fig leaf ice tea here), or glaze buns, tarts and cakes.

So, how to infuse? The amount will depend on what you are going for, but 5%-10% of the liquid weight is usually a good place to start. The length will also vary - overnight is often recommended for strong infusions, though I’ve had good results with shorter infusion times. In fact, my syrup with an overnight infusion was too much to handle and bordering on bitter - too much plant. So, whilst dairy can take a battering from a fig leaf, I’d avoid it for syrup infusions.

Converting any high-dairy recipe to include fig leaf is simple. Just give yourself extra time for the infusion. Whether it’s a custard tart or creme brulee, ice cream bases or panna cotta, I’d say a minimum of 20 minutes and a maximum of overnight, being wary that it can get bitter.

I couldn’t wax lyrical about fig leaf ice cream without giving you a recipe for it. So, I’m very excited to share a recipe from the extremely talented Marie Havnø Frank over on KP+. If you follow Marie on Instagram (and if you don’t, why not?!?!) then you’ll know she is a masterful ice cream maker.

Jam

The power of infusion strikes again. But rather than a long infusion, fig leaves can be added to any reducing jam and then removed before jarring and sealing. The super hot jam coaxes out the flavour, and, as a result, a hum of fig leaf is left to resound in your preserves. Because it is a fairly quick infusion, and since jams often have very strong tasting flavours to battle with, it’s definitely more of a ‘tasting note’ than a primary flavour like in ice cream. Want an extra helping of that fig leaf flavour? Do as @Robogeisha_tamonster suggests and “lay in one leaf per jar” before sealing. Very, very smart.

So, how much to use? I had good results making a 600g batch of peach and gooseberry jam with 30g of fig leaves (plus the baby leaves in the jar), a 5% infusion. Try it with your favourite jam recipe. Here’s a few to get you going: Camilla Wynne’s Strawberry Jam and Rhubarb Jam and or my summer Plum Jam here.

“Milk Jam”

This week when I was thinking about fig leaves, I started thinking about all the other loveable leaves in the world of cooking and baking. Suddenly I became fixated on one thing: Pandan leaves. I especially couldn’t stop thinking about pandan leaves in Hainanese-style kaya aka caramelised coconut jam.

Cooked over a bain-marie, kaya combines coconut milk and eggs along with palm sugar and pandan leaves to make a delicious, rich spread. Taking inspiration from this, I’ve created a recipe for a rich, fig-leaf scented spread which I’ll call Fig Leaf Milk Jam. Spread it on toast or use it as a filling, or loosen with cream and drizzle over ice cream.

Fig Leaf Powder

Not in the mood to infuse? Well, let me tell you about fig leaf powder. To make it, simply dry the leaves completely (best to use the oven, low and slow, 50c for 2 hours or try 120c for 15 minutes, then check every 5 minutes) - you want them to be totally crisp without taking on any colour. The vibrant green may dull a little, but don’t be perturbed.

Once dried, blitz in a food processor or spice grinder until fine dust. If you’re like me, you might end up with a few less-than-dry stems that don’t break down properly. In that case, just sift the powder and remove any large bits.

From here, you have a WORLD at your fingertips. Fig leaf powder can join the ranks of your spice rack and play a part in dry rubs - use it however you might use a dry green herb - to add a toasty, coconut note. Or, as chef, author and caterer Milli Taylor of Milli’s Catering suggested, it can be mixed with salt to create flavoured salt you can use to finish dishes. “I made a beautiful dish for a supper club once, of lamb and apricots with a fig leaf salt,” Milli tells me. “And I still think about it.”

Fig leaf powder is particularly useful to add flavour when there’s no liquid to infuse into (or if you’re just in a rush) - throw it into shortbread or scones along with your dry ingredients for a hit of the good stuff. Marie, my fig leaf spirit guide, has a favourite way to use it: In cheesecake. How much does she use, I wondered? “Last time [I made it], I used 1 tbsp of ground fig leaf powder to 600g cream cheese.”

This week I added fig leaf powder to whipped cream, along with the oil (we’ll get to that next) to create a beautifully speckled cream - around ½ tsp per 100g added real punch. I also used it, mixed with icing sugar, to dust the cake. You can find the recipe for the roll cake ft the powder here:

Fig leaf oil

Making plant oils is SUCH a handy skill to have up your sleeve. Because fats, e.g. neutral oils, are such excellent vehicles for flavour, quickly absorbing aromas, it’s a fantastic way to capture all the verdant goodness that fig leaf offers.

Once you’ve captured the fig leaf essence into oil, it can be used in myriad ways - it combines effortlessly into cake batters and buttercreams alike. You could use it to make salad dressings, or aiolis, or just drizzle it on top of your dishes or desserts for an extra lick of flavour.

Making your own is quick and easy but requires a bit of kit - a decent blender is essential. I start by blanching the fig leaves to soften slightly in water before shocking them in cold water. Once cool, I blend it with neutral oil at a ratio of 1:3 or 1:5 until the mixture turns a bright green. Because blenders heat up quite a bit because of the friction, the aroma of the fig leaf is released during the blitzing process. The final step is to pass the oil through muslin (or kitchen roll) over a sieve until the clear oil drips through. Although some recipes don’t advise blanching the fig leaves before blending with oil, I got the best results when I did. If you can’t be bothered to do this step, you can skip it, but I found I had to use a lot more oil to get it to blend easily.

I had a lot of fun incorporating into a super soft, fuzzy roll cake sponge this week:

Wrapping

Another way to impart the fig leaf flavour into your cooking is by using it similarly to banana or vine leaves. Despite fig leaves being widely available, this wrapping technique is not part of the typical tradition in the West. Though this is likely due to our cooler climate - I’m writing this newsletter in mid-July, and it is 17c and rainy - and we only grill about once a year on a dodgy half rusty bbq, it’s a shame.

By wrapping fish, poultry or vegetables in vine leaves before grilling or baking, the aromatic leaves impart a delicate fragrance to the dish. As well as this, because the leaves are naturally non-stick, you don’t need to add extra oil to cook. The leaves also help keep your food tender, steaming slightly and acting as a protective barrier and a handy serving plate.

But why stop there? I direct you to Natasha Pickowicz, James Beard nominated pastry chef and author of ‘More Than Cake’ who utilises fig leaves as “foraged parchment” to line cake tins.

She takes this idea further still in her book with a recipe for ‘leafy dinner rolls’, using leaves to line and cradle her pillowy dough. You can also see this technique in action in this recipe for ‘Higo de Fig’ - leaves are used to wrap around and cradle a preserved fig and nut paste. It’s quite romantic, really.

Base recipes

Fig leaf syrup

This all-purpose syrup uses a 1:2 sugar to water, so it isn’t too sweet. It won’t last as long in the fridge, but I prefer the less sweet flavour. You can play around with the ratio, but this works well in drinks and mixing into other recipes.

Ingredients

500ml water

30g fig leaves, washed

250g sugar

Method

To make the fig leaf syrup, bring the leaves, sugar and water to a boil for 10 minutes then leave to infuse for at least 2 hours. When cool, put into the fridge but taste it before you strain and leave it to infuse for longer if you aren’t happy with the taste.

Recipe ideas:

Peach and fig leaf ice tea recipe

Fig leaf oil

Oils are such a useful way to store flavours. It lasts 2-3 days in the fridge, but you can keep it in the freezer for months. Oils incorporate seamlessly into buttercreams and cake batters but can easily be used as a final drizzle to finish a dessert. The ratio of fig leaf to oil is up to you, but a 1:5 ratio of oil has good flow and flavour. For a more intense oil, you can go as low as 1:3.

Ingredients

30g Fig Leaves

150g Neutral oil like vegetable oil

Method

Heat a saucepan of water until boiling. Throw in leaves and submerge for 10-30 seconds until wilted. Move immediately into a bowl of ice water.

Once cool, squeeze out excess water and put blanched leaves into the bowl of your blender. Add neutral oil.

Blend for 5-10 minutes or until the oil has separated into tiny bits of plant fibre and a deep dark oil.

Pass through a sieve lined with a tea towel or muslin and let gravity do the work; It should pass in about 10 minutes.

Discard the pulp. Move oil into a clean container and keep it in the fridge for three days or freeze it for three months.

Recipe ideas:

1-2 tbsp whisked into Swiss meringue buttercream - use your favourite recipe or check out my classic base here.

Use in the base of an oil-based cake like chiffon. Click here for my fig leaf roll cake.

I don’t live in a climate that supports fig trees. Can I order dried fig leaves? Or would they be available at a specialty market?

Has anyone tried making an oil or an infusion using (very) dried leaves? This is the only way I could get my hands on some. They seem to be great for powder but I'm wondering how to get this beautiful scent into fats and dairy.