Kitchen Projects: A Field Guide to Preserving

by Camilla Wynne

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. It’s so wonderful to have you here.

As summer hurtles towards us, so does the promise of fruit, fruit everywhere; Picking up punnets of berries to take to the park, peaches that explode as you bite into them, roadside cherries that stain your fingers, mangoes that leave the memory of stickiness on you for hours. These moments with fruit are ethereal but… ephemeral. Blink and you miss it. Can’t summer fruits stick around for a bit longer? I’m not sure what this says about my psyche, but I find myself mourning the season before it’s even started.

Fortunately there is a glimmer of hope and it comes in the form of Camilla Wynne, our resident preserving expert and author two presering books, Jam Bake and Preservation Society Home Preserves. Camilla will be with us all summer long to show us how to hold onto these magical moments for longer. And ahead of peak fruit season beginning, she joins us today to share her field guide to preserving, an A-Z directory of sorts. Think of this as your pocket guide to all things preserved.

On KP+ Camilla is sharing her recipe for Rhubarb and Amarena Cherry jam - a recipe that walks the tightrope between spring and summer. We LOVE a transition.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level up version of this newsletter.By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter and get access to an amazing community, extra content, the full archive, and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come n join the gang!

Love

Nicola

A Field Guide to Preserving

I suppose one could accuse me of not living in the moment. For as soon as I’ve had my first fill of a new crop of fruit, I already have a mind towards how to put them up to enjoy them all year long. While of course there’s merit in being present and taking the days as they come, it’s undeniable that in many parts of the world this attitude would leave one bereft of local fruit much of the year. Preserving fruit means being able to enjoy it out of season, when the only local option where I live is apples (thanks to controlled atmosphere storage rooms, which keep this kind of fruit essentially in hibernation). In fact, even the fruits available seemingly year-round merit preserving at the height of their season—to capture peak flavour, to get the best prices and to facilitate future idleness. There is so much pleasure (and convenience) to be had in awaking on a cold, grey morning and being able to lazily pop open a jar of your own vanilla-perfumed applesauce to eat for breakfast.

Fruits, like most other fresh foods, are prone to spoilage caused by bacteria, mould and yeast. All those little guys need water to live, just like us. Lucky for them fruit are 75% water! In order to preserve fruit to enjoy many months from now, it’s necessary to either kill those microbes outright or to remove or tie up the fruit’s water content to starve them. There are a variety of ways to do this, many different techniques huddled under the same preserving umbrella. What follows is an explanation and guide to best practices for many of those techniques as you look towards the bacchanalian months of fruit ahead, whether you’re hoping to hoard or to prevent waste (or both!).

FREEZING

What is it?

A relatively modern method, this is the easiest path to preservation if you have spare room in your freezer. I most often use this method to preserve the small amounts of berries I harvest from my garden every day in the summer—as it’s not a particularly large or mature garden I don’t get a huge crop at once, but eventually I’ll have frozen enough for a batch of jam or a bake. I love freezing garden rhubarb all summer when other, flashier fruits are beckoning, as I know I’ll rejoice to bake a rhubarb crumble once winter comes. Keep in mind that freezing causes the water in the fruit’s cells to expand, rupturing the cells, so when thawed the juice will be separate from the fruit. For this reason, I like to weigh my frozen fruit while still frozen then either use it immediately or let it thaw, as it’s impossible to get an accurate weight otherwise.

How to do it

Wash and dry fruits, preparing in any way necessary, e.g. stemming and pitting cherries or peeling, coring and chopping pineapple. Place on a baking sheet in a single layer in the freezer (so the fruit doesn’t stick together) until frozen solid before transferring to a freezer bag or, ideally, vacuum packing. I invested in a home vacuum machine a few years ago and it’s paid for itself by eliminating food waste caused by freezer burn. If you don’t have one, DIY it by using a straw to suck out as much air as you can from the freezer bag for that vacuum effect!

CANDYING

What is it?

Long ago, when people couldn’t obtain just about any fruit at any time from anywhere, as in modern grocery stores, the fruit was candied so that it might be enjoyed out of season. This practice has spanned centuries and the globe, from fruit candied in honey in ancient China to the wet suckets (candied fruits in syrup) of medieval England that had their own special fork. With the advent of canning, refrigeration and global trade it’s no longer necessary to candy fruit for preservation, but like many traditional food preparation practices, we’ve developed a taste for candied fruit over the years and have made it a part of many of our beloved baked goods.

How to do it?

Nowadays, people rarely candy fruit at home. I obviously think this is a shame, which is why I’m writing a candied fruit cookbook! While it does require a little patience, the process is simple and the end result can be a versatile baking ingredient or confection in its own right. To learn how to do it, see this deep dive:

Kitchen Project #83: The art of candying fruit

Hello and welcome to this very exciting edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here. Today I have the honour of introducing something new for Kitchen Projects… our very first guest columnist! I firmly believe that knowledge is power, and I’m so excited to be able to invite guest writers to explore new techniques and skills with you (an…

DRYING

What is it?

Dehydrating is one of the most underrated preservation methods, in my opinion. Dried fruits make wonderful cake décor as well as an excellent snack and are great for baking. Dried apples, apricots, grapes and plums (aka raisins and prunes) are common but making your own will greatly improve your fruitcake or any other bake. It’s also a great opportunity to dry fruits you rarely see for sale like melon, citrus, kiwi, rhubarb, or strawberries.

How to do it

Use a food dehydrator if you have one, set to 60°C, but you can also set your oven to its lowest temperature (with the fan if possible), setting fruit on a wire rack set inside a rimmed baking sheet. Small berries and grapes can be dried as is, but larger fruits need to be sliced about ¼” thick. Arrange them in a single layer and allow to dry until they thoroughly dry but still pliable (otherwise they’ll be too hard to eat as is)—this can take anywhere from a few hours to overnight. Stored at room temperature in an airtight container, they’ll last for at least a month (but likely more).

To give fruit extra longevity and an ultra-pliable texture, soak it for at least one hour or up to overnight in hot simple syrup (equal parts sugar and water) and drain before drying.

ALCOHOL

What is it?

If you imbibe, preserving in alcohol is another easy technique. Alcohol is toxic to spoilage-causing microorganisms, so as long as fruit is completely submerged and kept in a cool place, it will last ages. The fruit will take on the flavour of the liquor in which it’s soaked and vice versa, so you end up with a lovely liqueur in addition to preserved fruit.

How to do it

Rumtopf (also known as Old Bachelor’s Jam) is a classic method, macerating berries and stone fruit with sugar and alcohol (brandy, rum, eau-de-vie or vodka). The mixture is added to throughout the summer as fruit ripens, then steeped for months to be enjoyed during Christmas holidays. I admit, however, that I personally prefer the simplicity of brandied sour cherries. A dark, meaty sour cherry steeped for months in lightly sweetened brandy (with the pits in the bottom of the jar if pitted, to lend an almond note) is a singular pleasure, whether on ice cream or cheesecake or in a cocktail. I love them so much that I make them every year whether I need to or not, so I probably have at least a few years’ worth in the fridge as I type.

FRUIT CHEESE

What is it?

Fruit cheese is a sliceable fruit paste set firm by virtue of its own natural pectin. The most recognizable example is probably membrillo (aka quince paste), but you can make fruit cheese with any high pectin fruit, such as apples, damsons and gooseberries. While they’re excellent served with cheese, I like to eat them just on their own, much as you would a pate de fruit. Molded in decorative tins, they make stunning, glossy little gifts. They keep for ages as well, as so much water is driven off in achieving that thick texture, and what’s left is tied up with sugar molecules, leaving no so-called ‘active’ water for microorganisms.

How to do it

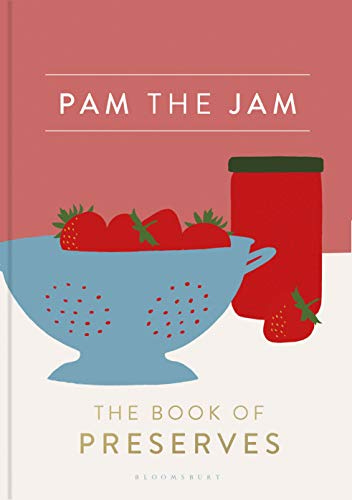

The best book for fruit cheese recipes is without a doubt Pam the Jam by the amazing Pam Corbin, which you should get if you have any interest whatsoever in preserving.

JAM

A common question I get in my jam workshops is about the difference between jam, jelly and marmalade. They’re all fruit cooked with sugar until they reach a point where enough water has cooked off and natural pectin has activated so that when cooled it forms a mesh, trapping what’s left of the water and achieving a set. The only difference is that jam uses pieces of fruit, jelly uses fruit juice, and marmalade uses citrus fruit, peel and all.

Jam needs to be poured hot (above 90°C) into hot, sterilized jars and sealed with new lids in order to be shelf stable. Any microorganisms present will have been eliminated simply by cooking the jam, which gets to temperatures exceeding 100°C, and the vacuum-sealed jar will prevent any new ones from being introduced until it’s opened. Shelf life once the jar is opened will be determined by the level of sugar in the jam, as sugar binds to water molecules, rendering them unavailable to microorganisms. The less sugar in the mix, the more available water.

How to do it

Most summer fruits are excellent for jam-making, though people will often choose fruit on the verge of decay, thinking of jam as a way to rescue fruit. This may work in small batches, but the best fruit to choose for jam is actually a mix of 75% perfectly ripe and 25% slightly underripe fruit, since levels of naturally-occurring pectin decline with ripeness. As well, new jam-makers will often first attempt with strawberries, being such a popular jam fruit, but they’re actually quite low in pectin and thus challenging for achieving a good set. Start with a fruit with high pectin levels, like currants or damsons.

Looking for Jam recipes? Check out these recipes available on Kitchen Projects now:

Pink grapefruit & toasted almond marmalade by Camilla Wynne (KP+)

Strawberry Jam by Camilla Wynne (KP+)

Quince Jam by Shadie Chahine @Shady_Kitchen

Stained Glass Jam by Camilla Wynne (KP+)

Rhubarb and Amarena Cherry Jam by Camilla Wynne (KP+)

COMPOTE

What is it?

I find I actually get through my stores of compote quicker than my stores of jam, maybe because I’m more likely to have yogurt for breakfast than toast. I sweeten my compotes to taste, using much less than when jam-making, as I’m not trying to achieve a set but rather just cooking off enough water to get a nice saucy texture. Most fruit will need a little water added to get things going, then you can simply cook it until it starts to break down.

How to do it

To preserve compote, the easiest option is freezing, but I prefer to can it to save room in my freezer. The term canning can be confusing, as the process is referred to as bottling in the UK. Jarring might be the most appropriate term, however. Once the compote is ready, it’s ladled into clean jars, up to the top for 2 piece jars and leaving a 1/3inch / 0.75cm headspace for Mason jars. The jars are then set in a pot of hot (but not boiling) water so that they’re covered by at least 5cm and brought to a boil. Simmer for 15 minutes, then let settle in the pot off the heat for 5 more minutes before removing from water and letting cool completely.

CANNED/BOTTLED FRUIT

What is it?

Presering up larger pieces of fruit, such as peach halves or pear quarters, is a little more complicated than compote, but worth the effort. Lining your shelves with jars of shelf-stable cooked fruit makes it easy to throw together bakes like Tarte Bourdaloue, which would otherwise require you to poach pears.

How to do it

You can preserve fruit in water, juice or syrup in any concentration; It's just important to note that the more sugar it contains, the longer it will last. Some fruits require a little precooking before going into the jar, usually warming through in syrup, while others go in raw—primarily fragile fruits such as raspberries or citrus supremes. That means that unlike jam, which reaches microorganism-killing temperatures just by cooking, canned fruits need to be heat processed (just like compote) to insure against spoilage. .Heat processing times are the amount of time a specific recipe needs to be heat treated in order for the center of the jar to reach that magic number, 100°C. These times depend on a number of factors including initial temperature, jar size, viscosity and acidity. Here’s an excellent resource for fruit heat processing times: https://nchfp.uga.edu/how/can2_fruit.html

CHUTNEY

What is it?

Let’s end on a savoury note. After all, you’ve got to have something to eat with cheese! Chutney is usually a mixture of fresh and dried fruit, vinegar, sugar, onions and spices. Slowly cooked down until thick, its texture is achieved by evaporation of water rather than the development of pectin chains as in jam. If it hits a temperature above 100°C for a prolonged period of time, it can be sealed in hot jars like jam, but otherwise it must be heat processed for 10 minutes.

How to do it

Since chutney contains low acid ingredients such as onions and garlic, it’s important to use a tested recipe, since the mixture must have a pH below 4.3 in order to prevent botulism from developing. That said, you can safely switch up similar ingredients (such as spices, vinegars or dried fruits) to put your own spin on a recipe as long as you keep the quantities the same.

GODSPEED!

I wish you a summer full of preserving, in whichever manner suits you as well as the fruit! But no matter which method you’ve chosen, LABEL and DATE what you’ve made! Though this may sound obvious, it’s worth repeating—even I sometimes lazily forget! It’s then you’ll find yourself squinting at something months down the line trying to decide if it’s raspberry or strawberry, and flipping through your diary to try to suss out when exactly you made it. Not that any of these will ever go bad in a dangerous way, but over time the taste, colour and texture will all deteriorate (though this will happen more slowly the more sugar you add). That’s why it’s best to try to implement a FIFO (first in, first out) system for your pantry, though I acknowledge this can be difficult if your partner is always sifting through there looking for the raspberry jam.

Camilla Wynne is a writer, recipe developer and teacher based in Toronto. She is the author of Jam Bake and Preservation Society Home Preserve. She is currently working on her third book about Candying fruit. She is a trained pastry chef and one of Canada's only Master Preservers. Find her at camillawynne.com or on instagram @camillawynne

Thank you so much for that very useful guide Camilla. 2022 was the first year in a while that I didn’t get round to making any jam or marmalade and I’m feeling it now (though fortunately I have a few friends who are better organised). But my favourite things to make are damson cheese (for which Pam

Corbyn ii indeed the guiding star) and damson chutney. I I have often contemplated bottling pears but not wanting to buy too much special equipment-- it seem that many households in North America have stash of canning supplies but it’s hard to find here. My next goals are pear-shaped. I would also love to dry pears at home because they can be hard to find just when I wanted them.

I Camila! Thank you for all the great information, it’s such a pleasure to read you! Let me ask you about syruping? How its done, and if it’s considered a preserving method? It seems to me a wonderful thing, a real syrup made with real fruit.

Thank you!