Kitchen Project #81: Peaches & Cream Cake

aka Karpatka, the airy cake of your dreams.

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

Today I’m squeezing the very last out of summer with a beautiful Polish dessert: Karpatka, though I’ve been nicknaming it Peaches and Cream cake.

Over on KP+, I’ll show you how to make a beautiful peach mousse, the best way to do it and how to preserve your fruit with pureeing. Click here for the recipe.

Kitchen Projects is an entirely reader-supported publication. To support the writing, it only £5 per month to join KP+. By becoming a member of KP+, you ensure this newsletter can continue and you also get access to extra content, recipes and giveaways, including access to the entire archive. I really hope to see you there:

Love,

Nicola

See ya, summer!

This is the last hurrah for summer. Sure, peaches may be past their best eating quality, but there are still great peach moments to be had. Savour them, since you may be waiting a while til the next one. I admit, it does feel a bit freaky to be writing about peaches when I got splashed with a huge great road puddle by bus whilst walking down Green Lanes earlier this week, but I wanted to tell you all about this very special dessert and couldn’t wait until next year:

Karpatka aka Polish Mountain cake is a choux-based cake that perhaps isn’t a cake at all. Gaining popularity in Poland in the 1970s and now a staple of bakeries across the country, this dessert is named after the Carpathian Mountains, a 1500km range that stretches from the Czech Republic to Romania. Rather simple but visually dramatic, it is a tried and tested combination of choux pastry and creamy filling. I came across this cake while researching Hungarian desserts (a story for another time), which managed to find its way into my wikipedia search radius. And thank goodness it did!

Although its origins are unclear, Karpatka seems to be a variation on the Mille-Feuille or Vanilla Slice/Napoleon (known as Krempita in Poland), but instead of puff pastry, you get wild ‘n’ wiggly tender-crisp choux. it’s the flavours and ingredients you know and love, in a new share-size format. This is also endlessly adaptable for dinner parties and would be a perfect centrepiece for any table. It is a simple recipe, but there are definitely a few steps to success. Today, we’re going to combine the classic peaches and cream:

Shall we do this?

Double peach

Over on KP+, I’m sharing a recipe for peach mousse, which will sit very happily in your Karpatka, or anywhere to be honest:

The choux pastry

I know we’ve covered this a few times, but revising the basics of choux is ALWAYS useful. I realise that choux is an area of stress for a lot of people, so the most important thing to remember is that Choux is steam-powered. As we make the choux, we are trapping lots of tiny water bubbles in the paste. When the choux goes into the oven, the water bubbles evaporate rapidly into steam, creating one big bubble. This also makes the pastry rise, and the crust, made of starch and egg proteins, begins to set, creating a crisp, thin crust, and trapping this big air bubble, leaving the inside completely hollow. Normally choux is piped into eclair shapes or buns, but today we are going freestyle, people.

If you’ve ever felt like choux was not for you, then this is the perfect place to get your choux stripes, should you wish. Rather than messing around with piping bags and craquelin, the paste is simply spread in the base of a cake tin and left to its own devices. It’s extremely forgiving - worried you’ve added too many eggs? Your Karpatka won’t mind!

Where Choux meets Yorkies

I’m the first to admit that Karpatka has giant Yorkshire pudding. For anyone reading this outside of the UK, a Yorkshire pudding is a staple of the British Sunday Roast. It is baked crisp, usually in a circular mould, and puffs around the edges in a bowl-like shape. In theory, it should be able to hold all your gravy. In the US, it’s known as a popover, though I don’t know how popular they are.

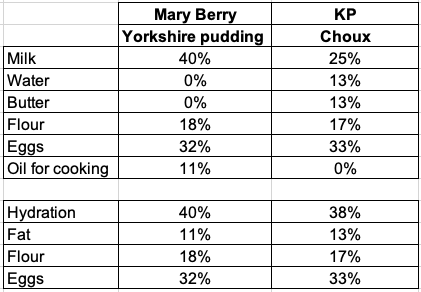

This got me thinking: how close ARE Yorkshire puddings and choux pastry? The method is different, sure, but there must be a close relation between the two, airy-crisp pastries. Looking at the ingredients side by side, you can see how similar they are:

I can never unsee this. This is very intriguing to me as it teaches us an important lesson about how ingredients are combined. And guess what the process that links them both is? Yes, you guessed it, my seemingly favourite topic - starch gelatinisation!

To give you a little reminder, starch gelatinisation is the moment when the starch meets water, and, with the help of heat, the granules absorb the water and swell, creating a mesh network and a thickened consistency. When you make choux, this happens before we bake it - the choux is partly cooked on the stovetop, which means the choux is at a pipeable consistency, allowing us to form shapes. As well as this, by semi-cooking the paste, you denature some of the gluten bonds, massively reducing the flour’s gluten-making abilities, though not removing them completely. The gluten chains will form, but they are impeded - the gluten is stretchy but not elastic, i.e. it won’t ‘spring back’ - this works in our favour when it comes to baking: The denatured gluten expands as the steam evaporates and this shape gets locked in by the starch and egg proteins setting.

When you make a Yorkshire pudding batter, the ingredients are all mixed, and the gelatinisation happens whilst it’s baking, rather than before. This means the mixture is fully liquid, so wouldn’t be much good for making beautiful shapes. As well as this, the gluten isn’t denatured ahead of time like the choux, so the bake is much wilder and less predictable - instead of creating a voluminous shell with a hollow inside, Yorkshire puddings only rise around the circumference, forming ‘U’ shape and are often unpredictable.

So, what came first? The first known sighting of a Yorkshire Pudding recipe is in 1737, in Hannah Glasse’s ‘The Art of Cookery’ (which you may remember is also the first book that mentioned trifle!). Choux pastry, however, is in the lead by a massive two centuries. Back in 1540, it’s thought that the celebrity chef du jour Pantarelli invented the dough in Florence whilst working for the Medici family. Here, choux pastry was originally called ‘pate au Chaud’ ie. HOT pastry because it was dried out over a hot flame. This slowly changed to ‘pate au choux’ over time.

Kitchen Projects is an entirely reader-supported publication. It only costs £5 per month, and your support makes this newsletter possible! By becoming a member of KP+, you directly support everything that goes into the weekly newsletter and get access to the extra content, recipes and giveaways, including the entire archive:

The deal with raising agents

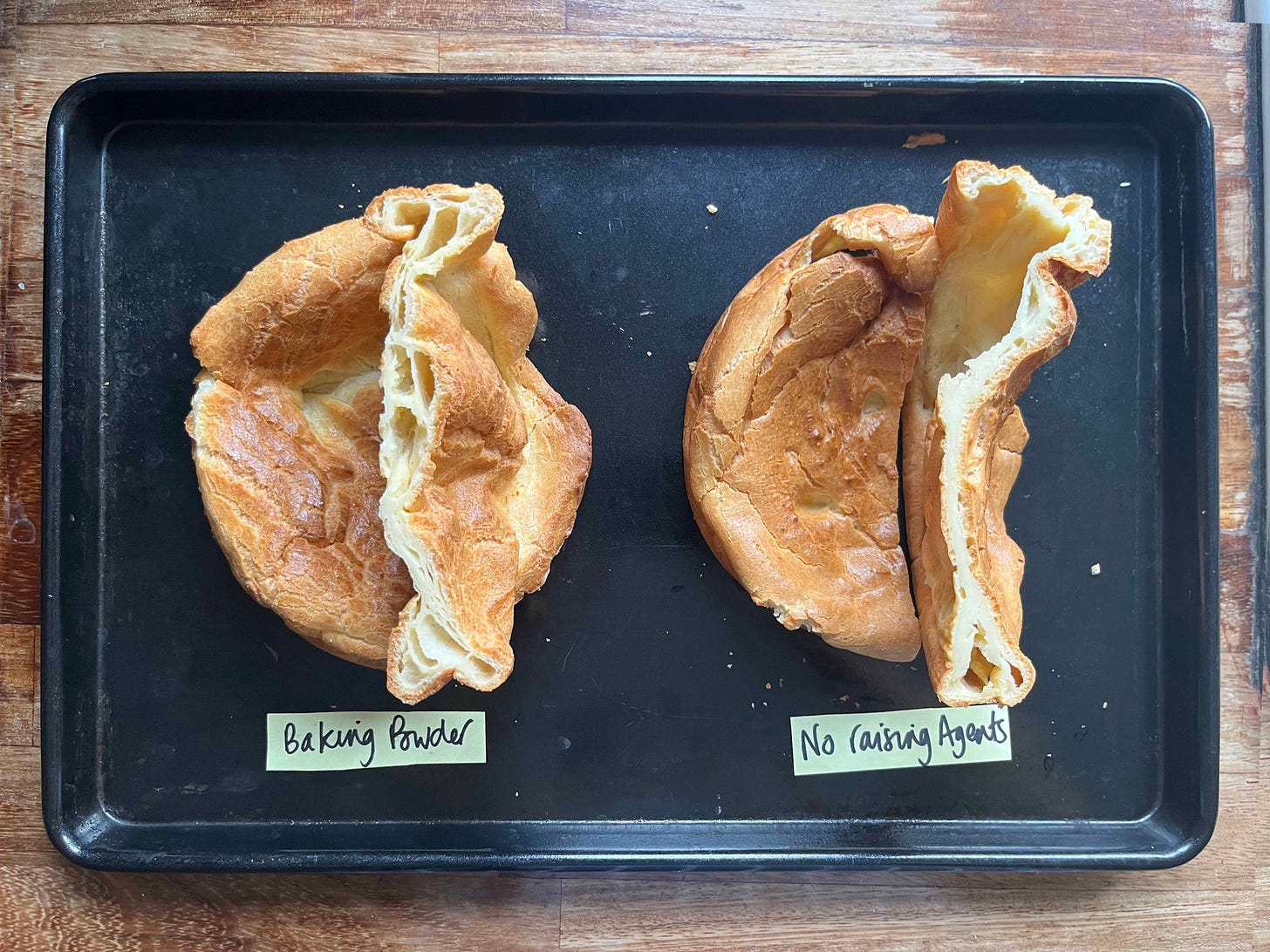

When I was investigating Karpatka, I saw something I’d never seen before: Baking powder! In choux pastry! I’m not often surprised by ingredient lists, but this did seem peculiar to me; Doesn’t choux rise enough? I put this to the test:

Intriguingly, the choux pastry with the baking powder puffed up in a much more irregular and exciting manner - as you can see, the layers of pastry was pushed apart, rather than forming a solid block. The choux pastry discs without baking powder still rose up but in a less dramatic pattern, resulting in a much thicker single-walled pastry. As we know, baking powder is a ‘double action’ raising agent. In the choux, we miss out on the initial reaction (as soon as it is hydrated!), but we really benefit from the second, heat-triggered reaction.

Solving for texture

The first time I made Karpatka, I was a bit disappointed in the results - the choux pastry was too thick and, as much as I love a flabby pancake (I actually do!), the answer was pretty simple: Reduce the quantity of choux. In an 8inch tin, I use just 200g choux paste per layer. It might seem a bit mean when you’re spreading it out but trust me - it’s enough. As well as this, I bake the paste for 40 minutes at 190c, which is longer (and with less dough) than most recipes recommend. This, to me, creates the perfect blend of airiness and doughiness:

Since the karpatka rests in the fridge once built, the choux pastry does lose crispness. If you are keen on a crisp choux hat, I recommend leaving the top off and placing it back on just before serving.

The filling

Most recipes out there use creme mousseline, a luxurious combination of pastry cream (starch thickened custard) and butter. I’m all for classic creme mousseline, but the high proportion of butter means it’s a real nightmare in the fridge. The butterfat goes completely solid, totally wrecking the once lush cream's texture. The mousseline will never recover without a re-whipping, which is not very helpful if it’s inside choux pastry. So, what to do?

I fell in LOVE with the mascarpone mousseline custard I made last summer; It is reliably firm and has the character of a creme legere or diplomat (custard folded with whipped cream), in that it remains smooth and airy in the fridge. Mascarpone and roasted peaches are also a winning combination.

Before we get onto the recipe, it must be noted that not all mascarpone is created equal. Despite having more fat, the supermarket mascarpone does not have as much body as the Italian deli mascarpone. I’m not sure why, but it must be to do with manufacturing methods. Although this cream does work with the supermarket brands, if you do have a way of getting some goods from the continent, you’ll really see the difference:

Adapting Karpatka

Adapting the Karpatka is easy - you have so many options. No peaches? Use any fruit you have to hand. Alternatively, you could spoon and swirl jam through the custard as you’re building it. You can also infuse the custard or make a chocolate cream instead. Or, over on KP+, I’ll show you how to make a peach mousse which, unsurprisingly, is a joy.

End-of-season peaches

Let’s be honest, there’s a high chance that these end-of-season peaches won’t be the best peaches they can be - they will very possibly be overripe and not as fragrant as they once were back in July. But rather than watch them go sad and wrinkly on the fruit stands, we can breathe life back into them and concentrate the flavours. For sad hard fruit, your best bet is poaching, which I covered on KP+ a few weeks ago. For sad, very ripe fruit, an intense high-heat roast will help concentrate the flavours and bring a new dimension to your fruit. The method is the same as the roasted plums, click here to read (though peaches, with their lower water content, can take a higher heat, FYI!)

Ok, let’s make it!

Karpatka aka Peaches & Cream cake

aka see you next time summer!

Choux base - the two discs are baked separately in 2 x 8inch tins

65g butter

65g water

65g milk

3g salt

15g sugar

90g self-raising flour, or plain flour with 4g baking powder

150g - 175g whole eggs

Mascarpone mousseline

300g milk

60g caster sugar

1 egg + 1 yolk (75g total)

30g cornflour

250g mascarpone

To assemble

Choux method

Heat the milk, water, butter, salt and sugar together. Bring to a rolling boil and stir to make sure the sugar/salt is dissolved

Sift the flour (and cocoa, if using) several times and add into your boiling liquid

Turn the heat down and stir rapidly until a smooth paste forms and a dry film is formed. If you have a thermometer probe, check that it is above 70c

Move paste into a bowl and either spread it out to cool down or paddle on a low speed if using a KitchenAid

Meanwhile, whisk the eggs - this makes them easier to combine

When you can touch the paste comfortably for 10 seconds, start to add the eggs. I do this in 3-4 additions, mixing well between each. The finished choux paste will be smooth and shiny and will ‘drop’ off the spoon when nudged. Choux can be kept in the fridge for 3 days before using.

Prepare two cake tins - I lined my cake tins, but I actually think paper at the bottom is fine. Split choux in half and spread 200g - 225g of paste in each tins, leaving the top slightly rough and wavy - use a palette knife to help. If you only have one tin, bake one at a time.

Bake at 190c fan for 35-40 minutes until well peaked, golden and crisp. Leave to cool completely.

Method - Mascarpone custard

Heat milk until simmering

Meanwhile, whisk together the whole egg, sugar and cornflour (I know it feels weird but just go with it)

Pour hot milk over the egg mixture and return to the stove

Cook for 3-4 mins over medium heat until boiling, whisking the whole time

Now, set aside to cool and gelatinise - make sure you put some cling film on the surface, so it doesn’t form a skin. You want it totally cold and firm before continuing on with this recipe.

When you’re ready to make the cream, try to make sure your mascarpone is room temp as it will combine more easily. It does have a tendency to be a bit lumpy so you just have to be prepared to work it!

Once that’s ready, beat the creme pat until smooth and no longer jelly-like . The easiest way to do this is in a Kitchen Aid bowl if you have one

Now fold/mix the two together - it should make a very thick cream. You can also do this in your KitchenAid with the paddle attachments. This is how it should look once combined:

Leave in the fridge until ready to use

Assembly method

Line one of the cake tins with acetate or paper. This will help you get a smooth edge.

Place your less cute choux disc in the base. Pile in the mascarpone custard, alternating with roasted peaches. Drizzle with peach roasting juices.

Place the most mountainous choux disc on top. Allow the cake to settle/reset by resting in the fridge for at least an hour.

Before serving, remove from tin and dust with icing sugar.

Will keep in the fridge for 3 days.

I’m hoping to make this and wonder if using a mix of bread flour and AP flour (+baking powder) would contribute to a high rise? Would you by chance have tried that before?

What if I don't have cornflour?