Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

What a festive edition we have today - I’m thrilled to hand you over to the capable hands of columnist Camilla Wynne for her for the 4-1-1 on a total classic: Christmas Pudding.

This recipe arrives here in your inbox purposefully on a Saturday so you can join in the tradition of stir-up Sunday, the time-honoured custom where households prepare their Christmas pudding on the last Sunday before advent (tomorrow!).

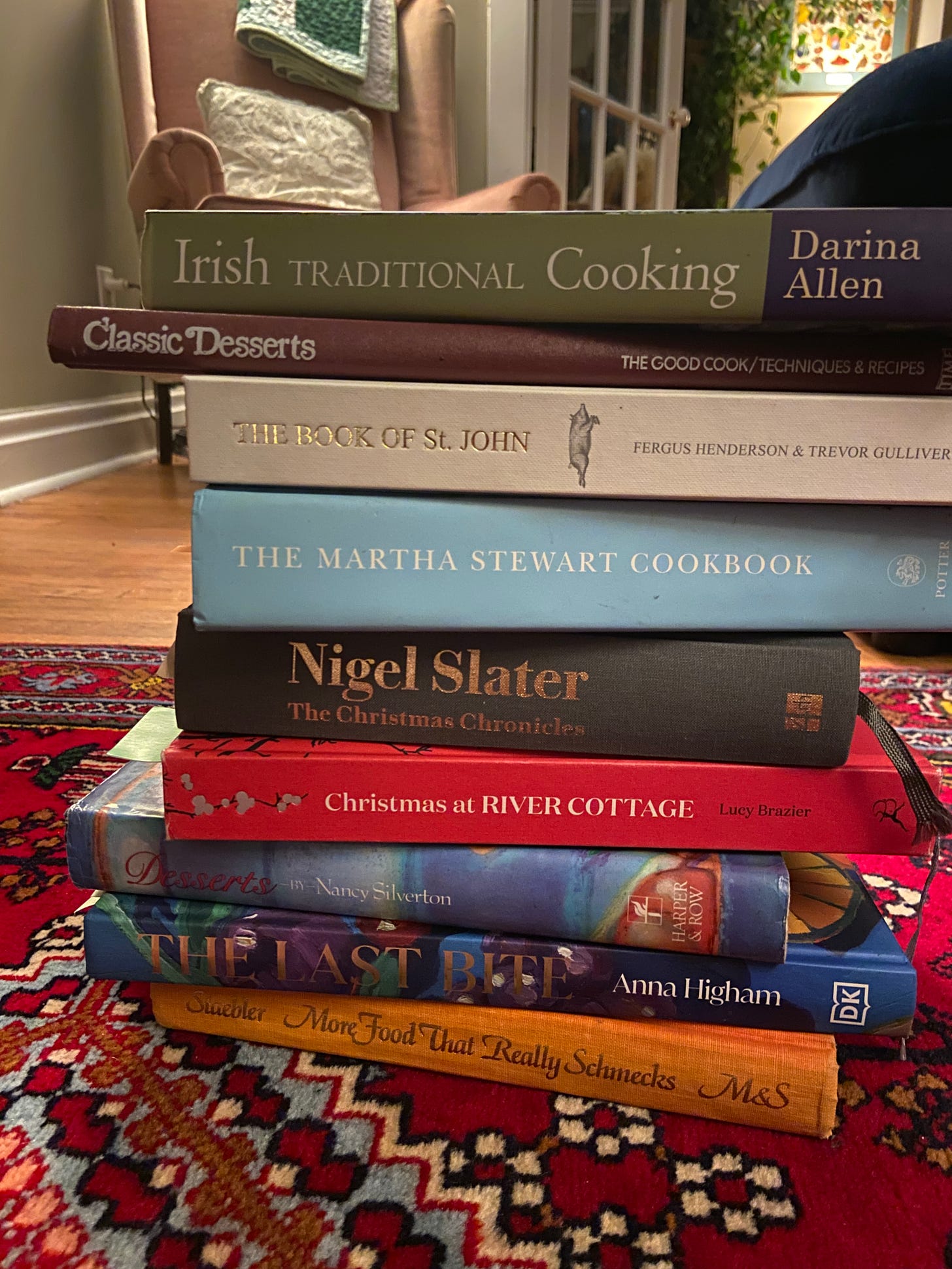

Over on KP+, the festive theme continues with my ultimate cookbook gift guide. I’m taking you on a tour of my personal library along with extra recommendations from some brilliant KP contributors and writers.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc., the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

PSST… I’ve written a book!

SIFT: The Elements of Great Baking is out next May and is available to pre-order now. Across 350 pages, I'll guide you through the fundamentals of baking and pastry through in-depth reference sections and well over 100 tried & tested recipes with stunning photography and incredible design. SIFT is the book I wish I'd had when I first started baking and I can’t wait to show you more.

A tale of Christmas Pudding

A classic dessert for Christmas dinner, the sight of the flaming brown orb fills its admirers with anticipatory joy, which likely flummoxes those who have yet to discover the charm of the Christmas pudding. Stir Up Sunday, the last Sunday before Advent is the traditional day to prepare your pudding, and it’s tomorrow!

Christmas pudding is also known as plum pudding, though this can be a bit of a misnomer, as recipes frequently don’t contain prunes—“plums” were used as a stand in for dried fruits in general. Like mincemeat, Christmas pudding originally contained meat, and wasn’t associated with Christmas at all in the early 15th century when it first became a dish. The first iteration of Christmas pudding would barely be recognizable to us today: served at the beginning of a meal, rather than as dessert, it began as a porridge and was later mostly steamed as a necessity since most households simply didn’t have an oven.

Made of chopped beef or mutton, onions and perhaps some root vegetables, dried fruit, breadcrumbs, wine, herbs and spices, it’s not what you'd really want after a meal of roast turkey or lamb. By the 16th century, though, the ingredients had been refined: to white meat, then just suet, and only the occasional carrot in place of the root vegetables. It finally became associated with Christmas in the 17th century only to have its consumption banned on December 25th, as Cromwell deemed it too pagan. Fortunately, the tradition held fast in spite of its detractors, and the recipe we know today has been established since about 1845 when Eliza Acton wrote the first recipe by name—fortunately after the invention of pudding cloth, eliminating the need to cook the pudding in animal skins or organs.

Stir Up Sunday has actually only been a thing since the late Victorian era and comes from the beginning of the day’s collect in the Book of Common Prayer. “Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people…” which has nothing to do with cooking, but why not get the pudding done well in advance the moment one is reminded of stirring? The tradition established by the 1920s of everyone in the household stirring the pudding while making a wish, east to west in honor of the wise men, retroactively imbued the pudding with more Christian significance, effectively erasing its banned Pagan origins. That said, most people today have never participated in a household stirring, as store-bought puddings have become increasingly popular. I, however, will implore you to make your own!

Traditionally made with luxurious, expensive ingredients like spices and dried fruit, this recipe has an unparalleled richness and enticing perfume. It’s pure, decadent comfort. Because I am a lover of fragrant quince, I employ it in this recipe shredded, candied and in spirit form. That said, if you have trouble finding quince or quince wine (or simply don’t want to spend the extra money!), you can use cooking apples in place of the shredded quince, another favorite candied fruit in place of the candied quince, and either a palatable sweet sherry or an apple brandy in lieu of quince wine. As with my mincemeat, I use cold grated brown butter in place of shredded suet to make it suitable for vegetarians and to account for the lack of easy access to quality suet where I live.

Steaming + Basins

Steamed puddings will be far more familiar to UK readers, though I fear they are slowly disappearing even in Britain. Most North Americans have likely never encountered one. What a shame! Not only does a steamed pudding leave the oven free for other pursuits, this method produces the moistest possible dessert anyone could hope for. Cuisines around the world employ steam to cook desserts, to great effect.

But how long to steam? That is the question! Depending on who you ask, it’s anywhere from 1 to 9 hours—the difference of a full night’s sleep! I found that the median (5 hours) worked best for my pudding, though of course cooking times will always vary from kitchen to kitchen.

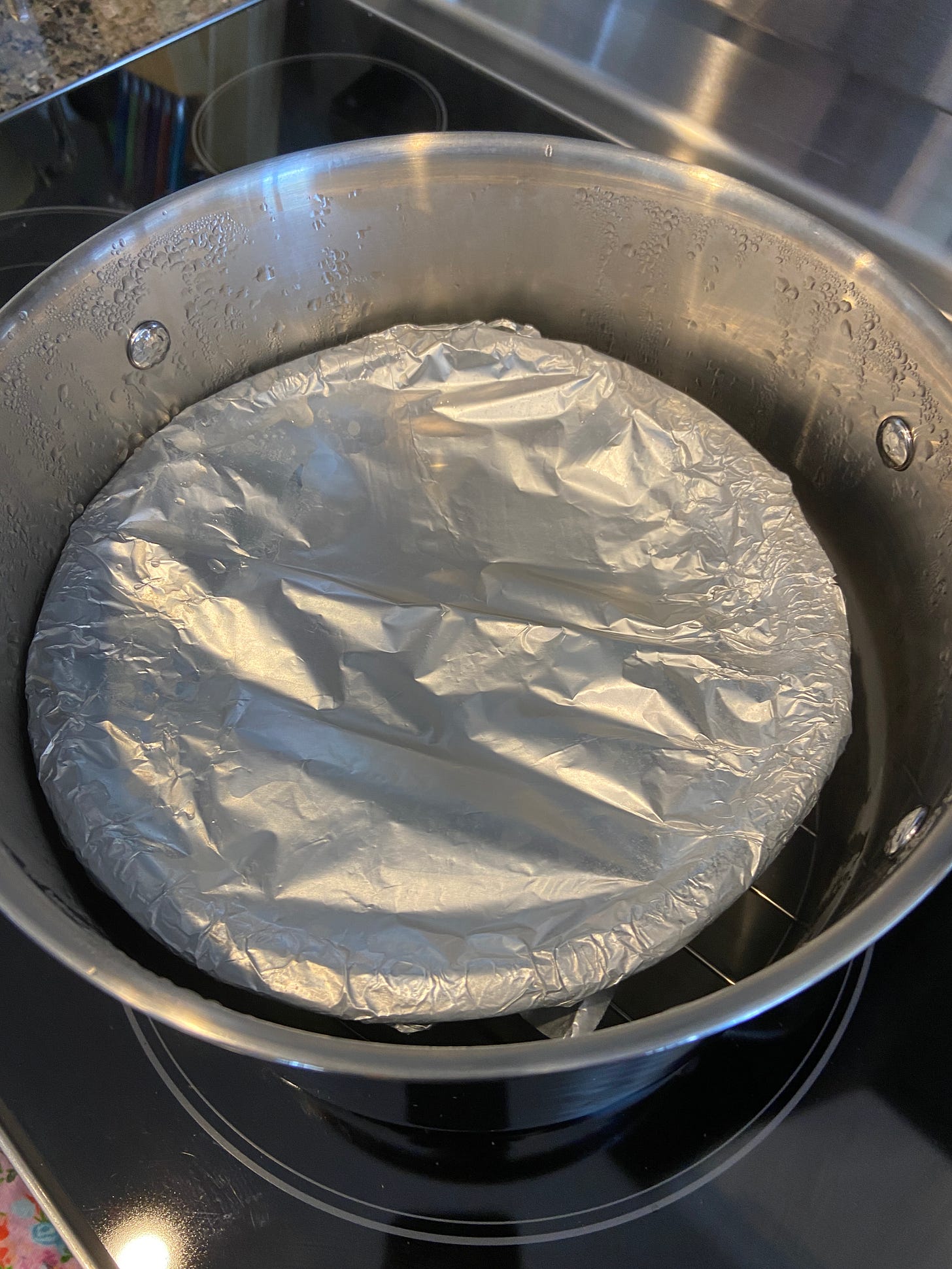

You’ll need a mold in which to cook the pudding. A pudding basin is the very tool meant for the job, but my guess is that if I don’t have one, neither will most of you. Fortunately, I’ve found that a small stainless steel bowl works like a charm, though the deeper it is the better your unmolded pudding will look, as height provides drama—fairly important for this sparsely decorated dessert. Some recipes call for a complicated method of pleating flour cloth or parchment to allow for the pudding’s expansion, but I just use a slightly larger bowl, which leaves some headspace at the top. The surface of the pudding is covered with a round of parchment then the bowl is sealed with crimped aluminum foil. Set on a trivet in a pot with water reaching halfway up the bowl, I’ve never found need of replacing the evaporated water at the low simmer I use for steaming, but do keep an eye, as it would be disastrous for the pot and pudding both for the water to run dry.

And because I’m a bit lazy, I don’t bother tying string around my bowl to help lift it out of the steamer, though I do recommend it if you’re enterprising, as I did give myself a bit of a steam burn getting one of them out of its pot. That said, if you have sturdy oven mitts, you should be alright.

The deal with aging

There are myriad opinions on how long to age your puddings—or indeed whether to do so at all. While some cooks insist that the pudding be aged for at least a year, this is a relatively new practice, beginning only in the 20th Century. After all, if Stir Up Sunday is the traditional day of pudding preparation, that would only leave about a month for aging. This should be enough time for the pudding’s flavors to really get to know each other and for the pudding to soak up a little extra booze.

Tradition aside, I find myself so busy during the holiday season that it just makes sense for me to get the pudding done as soon as the weather gets cold and I therefore begin dreaming of Christmas feasts. I do think that if you’re making one you might as well make two (as you’ll notice in the yield for the recipe that follows—though you can halve it without issue). If you’re hosting a big group, you’ll need both puddings, but for more modest celebrations, an extra pudding affords time saved next year and an opportunity to experiment. Age one pudding for just a month (or even eat it fresh!) and age the other for next year to see which you prefer. As someone who has always aged her pudding, I surprised myself while developing this recipe by perhaps preferring the fresh pudding; All of the flavors hadn't yet melded into one great Christmassy whole, I found notes of quince and peel came through more distinctly.

If you’ve aged fruitcake before, pudding isn’t too different. Once steamed and cooled, I replace the wax paper and foil for new, then stash it in the back of the fridge (though if you have a cold room or cellar that would work well and free up fridge space). Every few weeks that you remember, peel back the wrapping and dose it with a little brandy. (If you’re not into soaking things in booze, you could also freeze the pudding, defrosting overnight in the fridge before steaming.)

What about flaming?

Traditionally, Christmas pudding is presented aflame and garnished with a sprig of holly. The latter signifies Jesus’ crown of thorns, whereas the fire is a Pagan holdover. Not being a religious person and sadly not having ready access to holly, it’s the show-stopping flames that are essential for my pudding presentation.

Of course, setting dessert on fire is not without its perils. One wants the pudding—and nothing else!—covered in flickering blue flame. If the pudding is very hot, you should do fine dousing it in about 2 tablespoons of just warm brandy and igniting it straightaway with a match. I find it’s when you light the brandy before pouring it over the pudding that more gaffes can occur (see fig 1, wherein the bench upon which I was photographing the pudding as well as a cloth shopping bag were set alight). If you have a microwave, I find it the easiest way to heat the brandy, though because their power can vary, check it every 5 seconds or so. Otherwise, heat over medium-low in a small pot. Make sure the pudding is set on a platter with a large enough brim to contain any runaway licks of flame. If the fire does spread and escape the platter, quickly smother it, and try not to panic. It’s the brandy that’s on fire after all—not the actual bench, as much as it might look like it. Then quickly before the flames die out, kill the lights and present your pudding to the waiting feasters with a flourish.

Accompaniments

We all have our proclivities, and mine lean almost entirely towards custard, preferably dosed with additional brandy. That said, people enjoy their pudding with other accompaniments based on their own proclivities. Alongside custard, the most popular choice is hard sauce aka brandy butter (a UK vs USA distinction), which is indeed butter, sweetened with icing sugar and flavored with a generous amount of brandy. In spite of custard being nearly equally rich, there’s something that’s just too much for me in serving something as rich as a pudding with a flavored butter to accompany it. That said, I have all the respect for those who do honor this over-the-top tradition.

More austere people prefer just a glug of cold cream, and I can see how the contrast in temperatures could be pleasurable. Ice cream, on the other hand, is too extreme in my purview, though I know it’s enjoyed by some.

Leftovers

There’s something very satisfying about cutting a slab off a chilled chunk of leftover pudding, a dark and glistening terrazzo. Frankly, I think it’s nice just like that, eaten in front of the open fridge, but a custard-covered portion also reheats admirably in the microwave. You might also like to pan fry it in butter, crumble it up to swirl through ice cream or make cute little cake balls, but in all likelihood there won’t be much left over.

Alcohol Alternatives

If you don’t imbibe, you could sub out the booze in the pudding itself with what we call apple cider here- a cloudy sort of apple juice. And then just skip the feeding and flaming, though for the flaming I note that most of the alcohol, if not all, burns off-- it's more about the presentation for that bit.

Recipe: Christmas Pudding

Makes 2 puddings each serving 6 to 8

Ingredients

175 g prunes, chopped, approx 2cm pieces

155 g golden raisins

150 g candied quince, chopped (recipe below)

145 g currants

95 g diced candied peel

60 g diced candied ginger (crystallised or stem both work)

125 mL brandy, plus more for feeding and flaming

125 mL quince wine, sweet sherry or calvados

230 g quince (2 medium), peel, cored and grated

225 g brown butter, cold, grated

220g dark brown sugar

150 g eggs

140 g plain flour

125 g toasted slivered almonds

55 g fresh breadcrumbs

20 g egg yolk

18 g mixed spice

1 ½ tsp kosher salt

½ tsp baking powder

Method

In a medium bowl, combine prunes, raisins, candied quince, currants, candied peel and candied ginger. Add brandy and quince wine, stirring to combine. Cover and let sit overnight at room temperature.

The next day, grease two 1.25 L pudding basins or stainless steel bowls. A round of parchment at the bottom will help to unmold the cooked pudding. Set trivets on the bottoms of two lidded pots into which the puddings will fit. I use a small cooling rack as a trivet, but you could even just fashion a ring from aluminum foil.

In a large bowl, combine remaining ingredients. Add fruit mixture and stir it all together until well-combined (I find this easiest to do with clean hands!). Divide mixture evenly between the two prepared basins, smoothing the top. Place a round of parchment or wax paper on the surface of each pudding, then cover the basin tightly with aluminum foil (unless you are lucky enough to have a basin with a lid!).

Set each pudding inside its prepared pot and add water halfway up the side of the basin. Cover and bring to a boil, then lower the heat to a gentle simmer. Steam for 5 hours, until cooked through (you can test doneness by removing the coverings and sticking in a toothpick, which should come out with just a few moist crumbs attached).

Carefully remove puddings from pots. If serving immediately, remove coverings and invert onto a serving plate. To flame, gently heat about 30 mL brandy—I prefer 8 to 10 seconds in the microwave, but a small pot on medium-low work as well. Pour the warm brandy over the pudding and immediately set it alight with a match. Presently at the table while flaming! Serve with custard or brandy butter, as you wish.

If aging the puddings, let cool completely in their basins, then store somewhere cool (a cold room or refrigerator) for up to a year, feeding every few weeks with a little brandy. To reheat, steam for 2 hours, then proceed as above for serving.

To candy quince:

Peel and core a large quince; slice 1/4-inch thick. In a medium pot, combine 375 g water, 300 g sugar and 2 Tbsp glucose or light corn syrup. Bring to a boil over high heat, then add quince slices. Reduce heat to a gentle simmer and cook until quince are tender, pink and translucent, about 40 minutes. Cover and let sit overnight before draining and using, or store in a clean jar submerged in cooking syrup in the refrigerator for months.

Festive online workshops

Join me this Sunday for a fabulous foray into the world of confections-- just in time for holiday gifting. I'll help ease any fears you have about boiling sugar as we cook our way though buttery toffee, chewy caramels and bouncy marshmallows, with an emphasis on endlessly customizable flavor variations.

I've also got a homemade marzipan fruit party coming up in December and marmalade-making in January. For all the details, head to camillawynne.com/workshops

I am so excited about the amount of quince in this! Just it’s quite hard to find quince wine… got any recommendations?

JOLLY! Love this