Kitchen Project #88: Mince Pies (Part I)

Mincemeat deep dive with our preserving expert Camilla Wynne

Hello and welcome to this very exciting edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

Well, it was confirmed by the Queen of Christmas last week - it’s officially time. Yep, in celebration of it almost being the most wonderful time of the year, I am handing the reigns over to the Kitchen Projects resident preserving expert Camilla Wynne for the first installment of a 2-part Kitchen Project. It’s a classic: Mince Pies!

Camilla will be talking us through how to make your own fruit mincemeat, the history and the deal with aging. She gets DEEP! Next month, she’ll return with the recipe for the ultimate mince pie to put your mincemeat to good use.

Over on KP+, it’s equally as festive with Camilla’s Stained Glass jam; A perfect preserve for winter months. Click here for the recipe.

Kitchen Projects is 100% reader funded; By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter and get access to baking Q&As with me, extra content, community chat threads, and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month:

Love,

Nicola

All about Mincemeat

For ages I took for granted that everyone knew what mincemeat was—and that they liked it. Growing up, my granny’s mince tarts (we often abbreviated the name by dropping the “meat,” though I never once questioned what that word had to do with it) were one of the highlights of our Christmas celebrations. The flaky tarts’ dark centers were redolent of brandy and spice punctuated with plump dried fruit and candied peel amidst melting shreds of apple and suet. Heavenly. Yet as the daughter of a British man living in the Canadian Prairies, my favourite holiday treat was quite unusual, prompting bewildered stares from classmates.

Another thing I took for granted was that my granny—an expert maker of jams—made her own mincemeat. It was only as an adult that I learned that she, just like Nigella Lawson, doctored shop-bought mincemeat with brandy or rum! What a shame that so many people who love to cook and bake consider making mincemeat a chore. It’s not that I’d turn my nose up at the doctored stuff—it’s what my Aunt Sue still does, and her tarts are superlative. But homemade will always be better, made with real brandy and farmer’s market apples, free of industrial candied peel. What’s more, it gets you in the mood for the holidays, filling the kitchen with the delicious scents of delights to come.

A bit of history

As one might guess from the name, what we now know as mincemeat has significantly evolved since medieval times. In tracing its origins, mincemeat itself is indistinguishable from the form in which it is most commonly consumed, the mincemeat tart, but origin stories proliferate. The Oxford Companion to Food points to the charmingly named chewette as the first iteration, a small pastry filled with chopped meat, liver or fish plus hard-boiled eggs and ginger. On the other end of the size spectrum, the Larousse Gastronomique cites a “huge covered tart filled with ox tongue, chicken, eggs, sugar, raisins, lemon zest and spices.” While the chewette resembles the mincemeat tart in size, the huge tart contains more of the ingredients we associate with mincemeat today, so I suppose it’s anyone’s game, but generally people seem to agree the original had more in common with a meat pasty than what we know today.

By the 16th century, dried fruit, sugar and spices, though costly, became more widely available and mince or shred pies, as they became known, were a Christmas speciality. The next century saw the beef replaced at least in part by suet and the addition of brandy. The meat disappears almost entirely by the 20th century and is even less common now.

A number of years ago I gamely attempted a more historically accurate mincemeat, using an old Martha Stewart recipe. I opted for the one calling for ground beef chuck rather than the recipe using “scraggy” beef. I came away with the distinct impression that the beef was only really there because it was cheaper and more widely available than the dried fruit, sugar, spices and brandy that are the real stars of the show. While it had a slightly more savoury base note than the mincemeat I’d grown up with, I in no way preferred it, and it was certainly pricier.

Ingredients & Technique

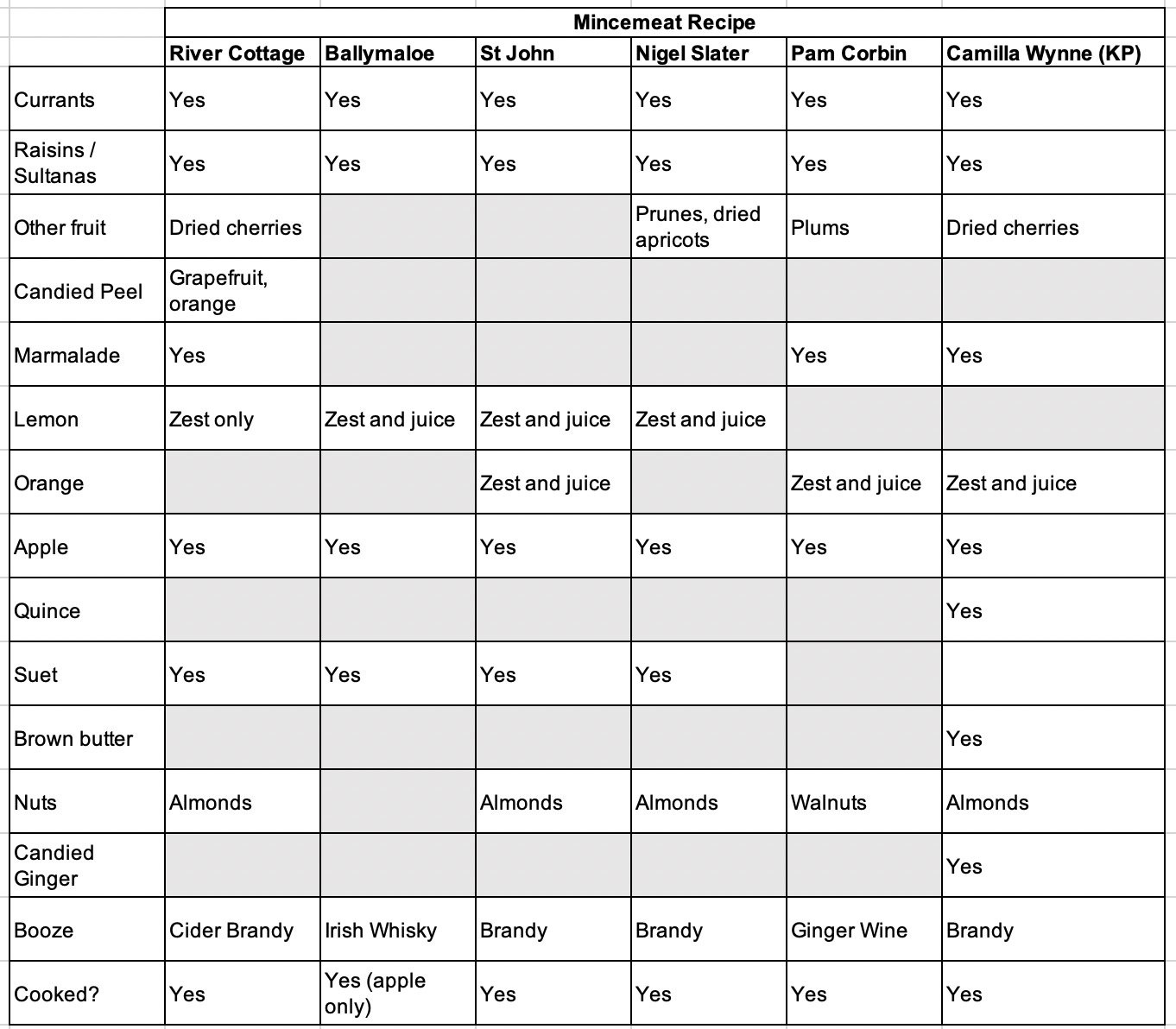

As I often do when I start thinking about developing my own recipe, I made a table of the different ingredients in various mincemeat recipes.

Let’s take a closer look.

Dried Fruit

As you can see above, currants and raisins (and/or sultanas—I’ve only just learned those are golden raisins, my favorite!) are essential to mincemeat. Some supplement with other dried fruit, but that’s just embellishment. (Nothing wrong with that, though—I like to throw in some dried sour cherries like in River Cottage.) It strikes me as a little odd that so many recipes use dried fruit when intending to age it for something like 6 months (thus prepared when more fresh fruit was available), but this wouldn’t have necessarily been the case centuries ago when mincemeat was created. And it’s true that they do both keep better and absorb flavors better for being dried.

Citrus

I was honestly shocked to see how few recipes called for candied citrus, which I would consider near-essential in any mincemeat. Presumably, there are various reasons for this blatant omission. In modern times it’s true that high-quality candied citrus can be hard to find and/or prohibitively expensive (though it’s actually quite simple to make at home). I was glad to see two recipes use marmalade, as the thick-cut variety can stand in quite well for candied peel in many preparations. For the rest, who knows? Maybe it’s a labour consideration at St. John? Traditionally unavailable in Ireland? At any rate, I insist on either candied peel or marmalade of quality.

Apple

Having replaced the beef as a “hygienic” alternative, it would seem that everyone uses apples as the base of their mincemeat, though Pam Corbin adds fresh plums as well, and Nigel Slater offers a recipe for quince-based mincemeat (aka quincemeat). I like to use about two-thirds apples and the quince for the rest. This adds intrigue while keeping costs in check.

What variety of apple you choose matters as well. Most British recipes will specify cooking apples, such as Bramleys, which break down nicely, helping to create a homogenous mixture, and aren’t as sweet as eating apples. Unfortunately, in North America the distinction between those kinds of apples generally aren’t made, mostly because it’s hard to get your hands on anything other than eating apples. Your best bet is to get your apples at the farmer’s market or nearby orchard, where you’ll hopefully be able to find varieties other than the supermarket standards and can speak with someone about which might be the best choice. I usually choose Cortlands, which are fairly easy to find in my area and break down nicely.

Suet

Suet is the hard, white fat from around the kidneys and loins of beef, lamb and mutton, and is really the holdout ingredients from the mincemeat of yore, lending richness to the mixture. While boxed shredded beef suet can be easily found in the UK, elsewhere in the world you’ll only find it fresh from a speciality butcher, if you find it at all. That said, Nigel Slater, who admits to often not making his own mincemeat, says you might as well not bother unless you’re using good quality fresh suet. Having once used fresh suet, however, I don’t feel the need to ever do so again! Being a bit squeamish and a little lazy, the arduous process of removing the membranous connective tissue, blood and other bits did not feel at all worth the trouble, though it’s possible I’m simply not a connoisseur.

The benefit of suet as compared to other fats—say, butter—is that it is 100% fat to butter’s roughly 82%. The rest of the latter is, of course, water, and the more water in any given mixture, the more susceptible it is to degradation by bacteria and mold. Determined to keep fat in the recipe, I opt for brown butter, which, in addition to being delicious, contains 15% less water than butter, making it a better choice for long term preservation.

Nuts

Like suet, nuts bring richness to the mincemeat. Happily, only one recipe excludes them. Almonds are the most common addition, generally slivered, and I like to toast them to amplify their flavour a bit. Some people don’t like the waxy texture nuts can have in a preserved mixture such as mincemeat, but I appreciate nuts in all their varying textures! That said, if you’re dealing with a nut allergy, simply omit à la Ballymaloe.

Alcohol

The liquors called for in mincemeat recipes runs the gamut, though they tend to be brown spirits. Rum, apple brandy, cognac, Irish whiskey, madeira and ginger wine all appeared in various recipes, but brandy is without a doubt the most popular choice. That’s what I’ve called for in my recipe, though if I had none I’d have no compunction substituting dark or golden rum, which play so well with spice, or Calvados to accentuate the apples (it’s a kind of brandy anyway). Omitting the alcohol or using fruit juice in its place is of course possible, but it will have consequences for long term preservation, as alcohol creates a hostile environment for any bacteria, mold or yeast seeking to take up residence.

To Cook or Not to Cook?

I am firmly on team cook, as are the recipes I consulted, though at Ballymaloe they cook only the apples. Cooking speeds up the process, dissolving the sugar and making the dried fruit absorb the liquid in the mixture faster. In fact, not cooking off some of the water in the mixture can have undesirable consequences. Cookery writer Delia Smith had to update her uncooked mincemeat recipe after readers complained of it fermenting during aging! She claims the updated recipe coats the apples in suet, thus halting potential fermentation, but I’d say it’s at least as likely that yeast can’t survive the heat of even a low oven, which would also cause the evaporation of the apple’s water content, making fermentation less likely even if yeast was introduced during bottling. That said, some enthusiasts ferment their mincemeat on purpose, claiming this was the case historically. I feel dubious of this claim…

The deal with aging

Ah, now for the question of aging. I have a sneaking suspicion that the instruction to age is what turns off the majority of would-be mincemeat-makers. But is it strictly necessary?

Perusing different recipes, you’ll find an enormous range of recommended aging times for mincemeat, which often differ from claims of how long you can keep it.

Ballymaloe recommends 3 weeks, adding, rather coyly, that it keeps “for months, or well over a year.” Mary Berry says to age it 6 months, whereas Graham Kerr prefers 2 years. Delia Smith has kept it 3 years but admits it’s better at 12 months. Wikipedia tops out the keeping claims at 10 years, though a footnote insists a citation is needed.

Just like jam, to which mincemeat is at the very least a cousin, if properly stored it can technically be kept indefinitely, though there’s always a point at which it reaches its peak amelioration from aging and inevitably begins to deteriorate. Exactly when that is, however, is difficult to pinpoint, and of course, being taste-based, is not an objective measurement. Like cellared wine, cave-aged cheese and dry-aged beef, mincemeat certainly improves with time, at least a certain amount, as flavors commingle and become more than the sum of their parts.

Long-term preservation, though, partly depends on the recipe itself and partly on how it’s stored. It should have the best chance of keeping the longest vacuum-sealed in a sterilized jar where microorganisms may not tread, but appertisation (the earliest form of canning) was only introduced in the early 19th century and people have been aging mincemeat since long before then. Even now, likely due to tradition, mincemeat seems to rarely be preserved this way. It’s the sugar and the alcohol that really contribute to its long-keeping reputation. Alcohol is toxic to the kinds of microorganisms that could cause decay, while sugar binds with the water in the mixture that those pests need to survive, and spices, though a minor player, have antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. What’s more, in the olden days, mincemeat would have been kept in cold cellars, where the growth of microorganisms would be sluggish, but which most of us no longer have. We do, however, all have refrigerators, which is where I personally choose to age my mincemeat. Since I know I’ll be using it come Christmas, which is soon enough, there’s no reason to go to the trouble of jarring it, but nor do I care to keep it room temperature and feed it regularly with brandy as they do at St. John—I already have a fruitcake (and a baby) to take care of!

So while mincemeat does improve with some time for all the ingredients to get to know one another, there’s no reason not to make it today—or even on Christmas Eve!—just because you won’t hit Mary Berry’s 6 month mark. I do like to make early just to get ahead of all the kitchen work the holiday brings (just because I delight in it doesn’t mean it’s not work, and there are only so many hours in the day), but, having recently been introduced to the delights of unaged fruitcake, I say as long as you make it, no matter when, you’ve done right by yourself.

Conclusion

There’s a Yorkshire tradition that says you should eat a mincemeat tart on each of the 12 days of Christmas, preferably in a different house every time, to ensure a happy year ahead. Whether or not it’s true, I never mind an excuse to eat more tarts, the making of which we will explore in much more detail in my next column. That said, the uses for mincemeat by no means stop there. While I prefer a mincemeat-enriched apple crumble (served with custard, of course), you can find recipes for incorporating it into sweet omelettes, steamed puddings, baked apples, toasted sandwiches, ice cream and banana bread. Possibilities abound.

Recipe: Mincemeat

This is a relatively light mincemeat, though it will darken as it ages. For something a little darker and sweeter, replace around 180 g of apples with raisins.

If you don’t have a quince handy, feel free to use more apples instead, but I like to get it’s particularly heavenly perfume and pink blush in wherever I can. Dried sour cherries can be replaced with another dried fruit such as prunes or apricots, but I do like the tartness they bring to the table. Dried cranberries would do that as well.

Makes enough mince for 36 deep tarts

550 g (~3) apples

250 g (1 large) quince

165 g (¾ cup) dark brown sugar

150 g (½ cup) thick-cut marmalade, chopped

100 g (¾ cup) currants

100 g (⅔ cup) golden raisins (aka sultanas)

85 g (½ cup) dried sour cherries

60 g (¼ cup) brown butter

50 g (⅓ cup) diced candied ginger

50 g (¼ cup + 2 Tbsp) toasted sliced almonds

1½ tsp Mixed Spice

Zest and juice of 1 orange

60 mL (¼ cup) brandy

Method

To make the mincemeat, peel, core, and coarsely grate the apples and quince.

Place them in a large pot, along with the sugar, marmalade, currants, raisins, cherries, butter, ginger, almonds, mixed spice, orange zest and juice. Heat on low, stirring occasionally, until the apples start to give off their juice.

Increase the heat to medium and cook, stirring occasionally, until the dried fruit looks plump and the quince is pinkish and tender. This will take about 30 minutes.

Remove from the heat, stir in the brandy, and let cool in the pot to room temperature.

This will keep in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 3 months.

If you’d like to keep it longer in the refrigerator, just add another 60 mL of brandy every few months and it should keep indefinitely (although there is, as you recall, a tipping point at which it begins to decline–also how much brandy do you want to use on this?).

Or you can pack it into sterilized jars while above 90°C to store in the pantry (or give as gifts!), in which case it will also keep indefinitely but likely be best in the space of a year.

Mixed Spice

Makes 60 ml (1/4 cup)

2 tsp whole cloves

6 allspice berries

1 star anise

3 green cardamom pods (husks discarded)

3 blades of mace (optional)

1T + 1t cinnamon

1 1/2 tsp ground ginger

1 tsp grated nutmeg

Method

Use a spice grinder (mine doubles as my coffee grinder!) to finely grind the cloves, allspice, star anise, cardamom seeds and mace, if using.

Transfer to a small jar and mix in the cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg.

This will keep at room temperature in a tightly sealed for at least six months.

I had some dodgy quince I needed to use up quickly, so I made a batch of this tonight. I typically use Delia's recipe, but this was also lovely--it smells and tastes absolutely divine! I'm in the US, so I used some pumpkin pie spice in place of mixed spice, and I think that substitution worked well. Very excited to have mincemeat for the mince pie season to come! Thanks for the lovely recipe!

I used to dislike mince pies, but looking at this ingredient list, I realise that it’s probably the taste of alcohol that I dislike ( I like fruit a lot, and like spices too 🤔) now thinking I should have a go at making mincemeat this year minus alcohol 😄