Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. It’s so wonderful to have you here.

Today I’m sharing a recipe that I capital ‘L’ Love: A mango custard tart. It wasn’t an easy journey getting to this one, but I’m so excited to share my adventures into this fragrant, wobbly dream tart with you.

Over on KP+, Tarunima Sinha (aka mylittlecaketin) has written a beautiful musing on growing up with mangoes and what the season means to her. She also fills us in on all the details of how best to enjoy Indian mango season, including the best way to prep them. As an added extra, I’m sharing my recipe for a dreamy creamy Mango pannacotta that is packed with fresh flavour. Click here for the recipe.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level up version of this newsletter.By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter and get access to an amazing community, extra content, the full archive, and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come n join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

WLTM: Something creamy with great wobble

When it comes to pastry, the sheer amount of ways to go about things, can be overwhelming. If you think of flavour profiles as ‘A’ and the final product as ‘B’, there are just so many routes (or ‘recipes’ as we like to call them) that connect the two.

One of the best examples of this is anything set and creamy. Transforming a pourable liquid or fruit puree into a wobbling mass that melts in the mouth is probably one of the most satisfying things to do in baking.

From eggs to gelatin, acid to cornflour, there are so many ways to create texture. But which is best? Each has its own benefits; some create a more luscious mouthfeel, whilst others favour flavour.

I looked into this conundrum two years ago when exploring the world of creamy lemon things, but compared to a lot of flavours, making something taste of lemon is like playing a game on easy mode; It has such potent acidity that the flavour shines through, strong enough to battle butter, eggs and sugar. So what about something more delicate like mango?

Mango season

If you didn’t know, we are in peak Indian mango season right now, people! Until last year, I wasn’t even aware of Indian mango season - it had just passed me by. I’d heard of alphonso mango, but never properly appreciated it for the jewel that it is. b

Eating a ripe mango is a unique pleasure - when a mango is good, I struggle to imagine a fruit ever being better. It has an extraordinary flavour - sweet, fruity, floral, acidic, it has it all. And though this flavour is distinct, it can easily be lost. The complexity is easily dulled. I mean, the experience of eating a ripe mango pretty much inspired Brian Levy to write his book ‘Good and Sweet’; There’s just something magical about the fruit.

While I maintain the best way to eat a mango is greedily from a chopping board, I decided to figure out a dessert (or two) that could really let a fragrant mango shine. And I could not get the image of a shining, wobbling mango custard tart out of my mind. Especially a bright orange version made with the peak season alphonso or kesar mangoes; I mean, how hard could it be?

(spoiler: it was… very hard.)

Shall we dive in?

How to make a custard? Let me count the ways…

Let’s first look at some simple set cream/custard equations:

Fruit puree + sugar + Gelatin = jelly.

Fruit puree + sugar + fat + gelatin = panna cotta.

Fruit puree + sugar + eggs + butter = curd or custard

Fruit puree + sugar + eggs + cream = custard

I dived right in, coming up with a few versions to test out as below:

Each of these tests had a varying success rate - I think the easiest way to talk through what is happening in each one is by breaking down the defining elements: Fat, eggs and setting agents. And, of course, the starring role of the mango puree itself (and the little tweaks of seasoning). Just look at the varying colours (ranging from dijon yellow to bright orange!) below:

Let’s run through the key factors.

Fat

Fat is important for mouthfeel and flavour, but it also has a role in keeping custards smooth - when we make custards, we are trying to keep the egg proteins away from each other for as long as possible. When egg proteins clump together when heated, they go from a liquid to a solid in a process known as coagulating’. Fat is quite good at coating the egg proteins and preventing them from making bonds too quickly, resulting in a rise in coagulation temperature.

What about butter?

The trouble is, most fat has its own inherent flavour and is usually quite strong. I love butter, but it can be a dominating flavour. With very acidic fruits, like lemon, it’s possible to successfully dilute it with fat, like butter in the case of curds, or cream in the case of Tarte au Citron, while maintaining a strong lip-puckering response. Mango is not so lucky - the perfume is lost easily, especially when combined with a lot of fat. It’s even more fatal when paired with cream, which has a high water content, meaning we need even more eggs - which also have flavour - to ensure it sets.

The deal with coconut oil

One of my favourite tricks up my pastry sleeve is deodorised coconut oil. This is such a secret weapon - it looks like coconut oil, and it behaves like coconut oil but smell or taste? Gone! Sure, it is less nutritious since it has undergone heat treatment, but it has so many other benefits. Coconut oil is very useful for replacing butter because it has a melting point of 25c-27c, which means it really mimics a melty mouthfeel; When it’s firm, it is harder than butter which means anything made with coconut oil will be extremely firm when it comes straight from the fridge but becomes fudgy at room temperature.

I realise that deodorised coconut oil might not be a priority if you are a casual baker, but I think it’s incredibly useful to have around. In the case of mango, we are increasing the fat content of the custard without adding any flavour - this means we reap the benefits of mouthfeel without the flavour battle that comes with butter. I absolutely adored the version made with deodorised coconut oil; It had an incredible texture and was pleasingly firm and wobbly.

FYI - I did try making it with deodorised coconut oil - although coconut and mango are good friends, the flavour was too strong for me. So, I’d avoid that and instead use butter.

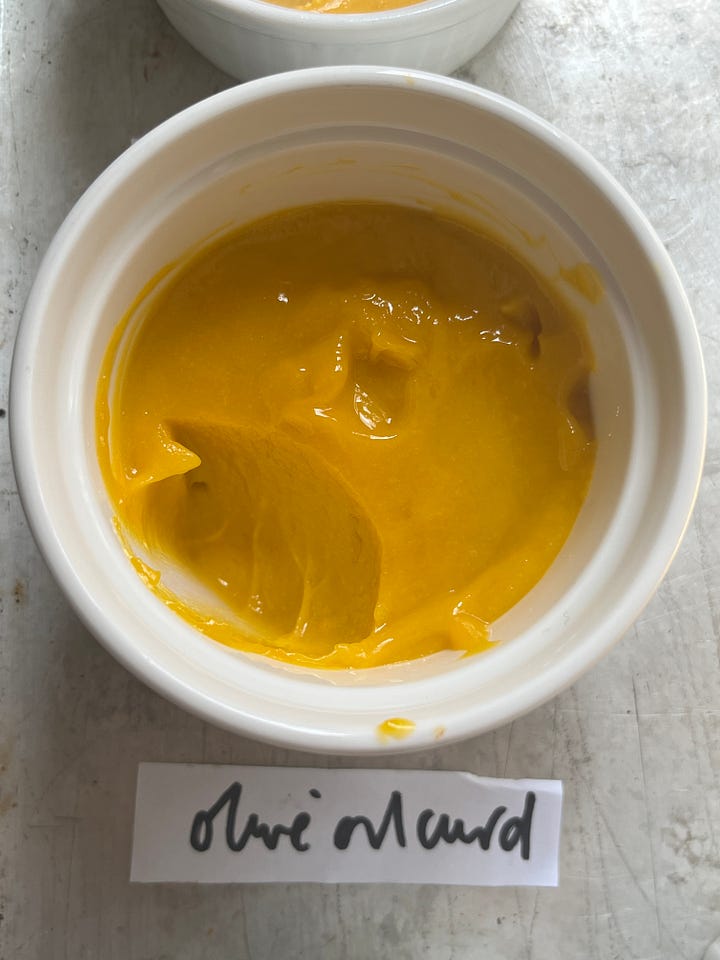

Olive oil and ganache

While the olive oil curd looked lush, the flavour of the olive oil was overwhelming. I’ve never had this issue when it’s head-to-head with lemon; In this case, the two work together to make a united flavour front - but the poor mango was lost. RIP mango. And although the ganache had a pleasing texture and the largest amount of mango compared to the other tests, the flavour just didn’t sing.

Back to butter

So, you know how I said the flavour of butter is too strong? I stand by that, but there IS a sweet spot - by reducing the amount of butter in the final custard/curd to just 10%, we retain some of the lusciousness but let the mango sing! I tested a few variations out - it does work to omit the fat completely, but I loved at least a little to make it extra smooth and rich:

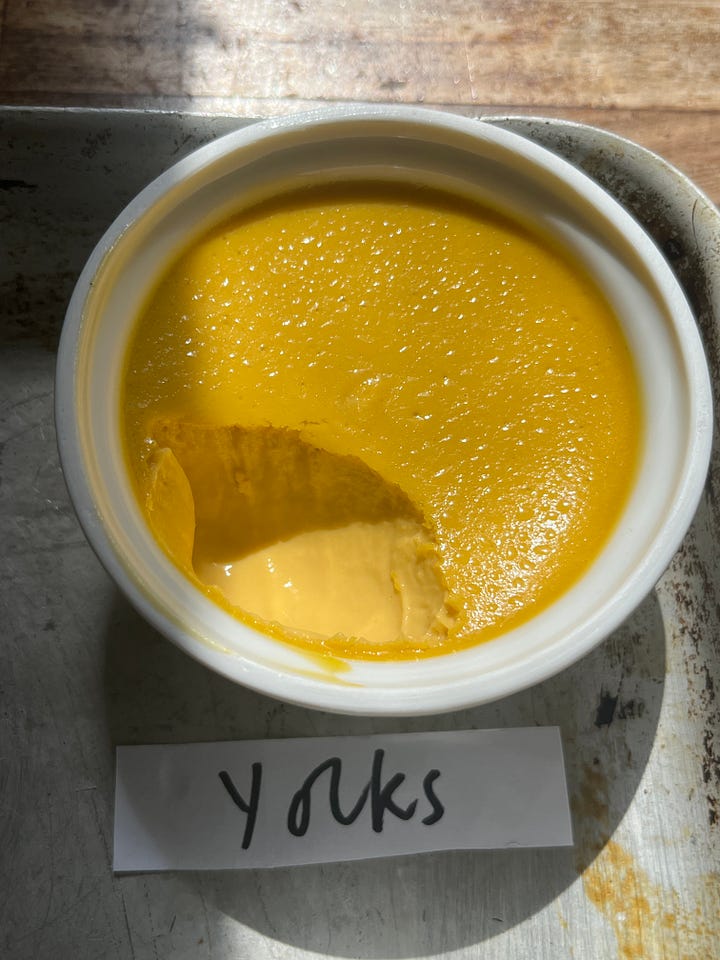

Eggs

Eggs set custard by coagulation. This is when the proteins turn from a liquid to a solid. It’s an irreversible action (you truly cannot uncook an egg, I’ve tried during a stressful shift as a young chef who definitely over-promised her custard-making ability). We most commonly see whole eggs (as in lemon tart) or egg yolks (as in almost all custards), but I had a lot of fun exploring the world of egg white custards in this newsletter.

Although the idea of making an egg white custard might seem odd, I assure you it is not (click here to read more about it)! Benefits of an egg white custard include a firmer set, owing to the larger amount of proteins available in egg whites compared to yolks. The other benefit is a more neutral taste - while delicious and rich, egg yolks have inherent flavour, whilst egg whites allow other flavours to shine. Surprisingly, the egg white and egg yolk custard were incredibly similar - both smooth and lush. But sadly, the mango was lost.

Custards vary in many ways, but the ratio of eggs to liquid is one I take most notice of - the fewer eggs, the more something will flow once set. Compare a pouring custard-like creme anglaise to a wobbling custard tart. As well as this, the more naturally thick something is, the fewer eggs you need to get a successful texture. Consider a baked cheesecake, where eggs make up just 10% of the mixture, and a custard tart, which is closer to 20%. This is where I ran into issues with the tinned mango puree. Tinned mango puree - at least the stuff I got my hands on - was much more liquid than the fresh puree - it would pour off a spoon, rather than dollop like fresh does. As a result, if using tinned puree, I found it necessary to increase the amount of eggs by about 20% to achieve a similar set.

Though the wobble of the tart will give you a decent indication of when the custard is ready to remove from the oven, I find it most reliable to temp the tart using a thermometer probe. Aim for 76c - 78c for a firm but giving set.

Setting agents

Beyond egg coagulation, when it comes to thickening, we have a few options. Two of the most popular options are starch and gelatin.

When dissolved in water and heated, the starch granules absorb the water and begin to swell, producing a thickened consistency. Though you can make curd without cornflour, I decided to opt for a version with it for some extra body (and to give us something to compare, of course!); The amount of starch in the curd is about 2.5x less than we use for traditional pastry cream. As a result, the final effect is less jellied and more of a flowing but spoonable gel. As outlined above, the mango curd was a bit of a disappointment - the flavour of mango is lost.

Gelatin is a protein that interacts with water molecules - the amino acids move apart when heated, and as it cools, they re-bond, trapping liquid within. This results in a springy texture in fruit jellies. When you add something like cream, which has a smaller or limited amount of water, the gelatin has less water to interact with, so we use less gelatin. The gelatin test had the highest proportion of mango in, with just a small amount of cream to improve the texture, and it was a knock out. The floral notes of the mango remained in tact. I loved this version and will 1000% be using this to fill tarts and make desserts whenever I get my hands on mangoes. I’ll be sharing the recipe for mango panna cotta, my dream formula, on KP+:

The role of acid

Seasoning our food helps it taste more like itself; Acid can help open up flavours, cut through fat and make our mouth water. This uptick in saliva expands the ‘canvas’ available since we need it to experience flavour. Before they ripen, mangoes are acidic; Green mangoes have a Ph of 3-4 while ripe mangoes mellow to 5.5-6. This is because the acids (citric and malic), convert to sugars during the ripening process.

To make my mango custard sing against the yolks, I knew acid would help. The three options to me were obviously lime juice, citric acid or amchoor.

Lime is often paired with mango, but with such a sensitive flavour balance, I feared throwing things off (and instead have deployed it in the crust, don’t worry!).

Amchoor is a spice made from dried, green mangoes. It is delightfully sour and aromatic. I tried it in one of the recipes and actually, the flavour didn’t read particularly well; It is much better sprinkled on top (imagine dusting the custard tart with it before baking like nutmeg in a classic custard tart?! Slay.)

Citric acid is an acid naturally found in all citrus fruits. It is potent - it will brighten up any ‘cooked’ fruit flavours (see Camilla Wynne’s strawberry jam) and bring a zing without the baggage of lots of liquid. It is a generic sour that can be added in very small quantities. Adding ⅛ th - ¼ tsp per 100g mango puree was a win for me, though this will depend mango to mago.

Mango aroma compounds

Perfectly ripe mangoes really do have the most extraordinary flavour - they are sweet, fruity, floral. Ever since finding out that blueberry and coriander seed share an aroma compound, I’ve become quite obsessed with researching these. According to this article, Mango contains five main aroma compounds including “γ-terpinene, 1-hexanol, hexanal, terpinolene trans-2-heptenal, and p-cymene.” Flavours often go well together if they have common compounds - it’s no surprise that mango shares aromas with lemon, orange peels, yellow peppers, blackberries, pink pomelo, tangerines, raspberries and grapes. More unique shared aromas include hyssop, black walnuts, corn, cumin, sage, rosemary and, extraordinarily, scent gland secretion of the rice stink bug.

What about tinned mango?

Tinned mango, for its convenience and guaranteed flavour punch, are popular in baking recipes. The back of the tin reveals it has about 10% sugar (in line with how much I was sweetening the custards, which was a lucky coincidence!), water and citric acid. As mentioned in the egg section, this additional water does considerably change the consistency of the puree. And I see the use of citric acid as commercially backed thumbs up to go ahead with a pinch in my own custard.

The finishing touches

Although this tart is beautiful without, if you really want to pull out all the stops, covering the tart in thin slices of mangoes really does take it to the next level - it’s just so inviting. Because the slices are very thin, you actually only need 1.5 mangoes to cover it, but it does make a difference to the final look. Plus the extra mango flavour just brings it all together. This is totally optional - you could also serve a few slices on the side of each slice, too, if you aren’t in a decorating mood. Finishing with a big dollop of yoghurt cream is a wonderful way to finish it off, too.

I decided to make this tart with a simple crumb crust, but it would be stunning with a sweet shortcrust pastry, too - just make sure it’s well blind baked and sealed several times before adding the mango custard.

Alright, let’s make it!

Mango Custard Tart

Makes 1 x 8inch tart, serves 6-8

Mango Custard

385g Fresh Mango Puree (I used Alphonso and I got about 130g flesh per mango, so you need about 3)

60g Caster Sugar

60g Butter*

95g Egg Yolks (about 6. You can also use 1 x whole egg and 45g Egg Yolks)**

½ - ¾ tsp Citric Acid (optional)

¼ tsp Flaky salt

Crumb crust

185g Biscuits – either home made (like 3pm oat biscuits), graham crackers or digestives work well

1 lime, zested

40g – 80g Butter (shop bought biscuits tend to need more butter, whilst home made tend to need less!)

Yoghurt Cream

100g Thick Greek yoghurt

100g Double cream

Optional: 15g Caster sugar

Plus lime zest, or amchoor to finish

*For a richer texture, use up to 80g butter. If you are used deodorised coconut oil, use 95g for the most rich, firm texture without adding flavour.

**If you are using tinned mango, which is quite liquid, increase egg quantity by 25% and omit the sugar.

Method

First make the crumb: Blitz the biscuits into crumbs in a food processor or bash them up in a sealed bag using a rolling pin. Move into a bowl and grate in the lime zest.

Melt the butter then pour it into the crumb, agitating it as you go. You want to add enough that it holds together in a wet clump, but not much it feels greasy. This is not an exact science and it will depend on what biscuit you are using! Remember, you can always add more butter but you can’t take it away.

Take a loose bottomed 8inch tart tin and put a circle of greaseproof at the base to make it easier to remove later.

Pour the buttered crumb into it. First make the edges, then press the base in.

Heat oven to 170c fan. Bake the crumb case for 10 minutes until a little browned in places. If the crumb moves at all, press it back into shape gently using a spoon.

Remove flesh from mangoes, removing as much as possible. (See here for more info) Blend to a puree and pour into a bowl. Whisk in the sugar and egg yolks.

Melt the butter in a small saucepan then pour into the mango custard and whisk well. Finally add the salt and citric acid. Taste and season with citric and salt if needed. Pass through a sieve then pour into the prepared tart case. Smooth the top with palette knife.

Heat oven to 140c fan. Bake the custard tart until it reaches 76c-79c in the middle. Start checking at 20 minutes, but in my oven (which is unpredictable at temperatures below 170c), it took me about 30-40 minutes. It will still shake and wobble, though it will look more firm and glossy.

Remove from the oven and leave to cool for 30 minutes at room temp before transferring to the fridge to chill completely, around 3-4 hours. Overnight if you can!

If making the mango decoration, it’s best to do this before the tart chills so the fresh mango melds to the top better. Slice the mango either side of the pit (just look for the stem on top of the mango then slice either side of that) and carefully remove the lovely ‘cheeks’ using a sharp knife. Slice the mango into very thin slices, around 2mm if you can. Layer onto the tart. Wait to add the lime zest before serving as it goes a bit dry in the fridge.

To make the cream, whip the yoghurt and double cream (and sugar, if using) together until thick. Spoon generously onto slices of tart (remember it’s best to cut with a super sharp knife or a sharp serrated one, and please please god forbid clean your knife between slices)

So excited to make this!! When making the custard, do you have to heat the mango puree before adding the yolks/sugar? And then put it back on the heat like a traditional custard? Or not required? Also, just to double check, there is no need for any setting agent such as gelatine? Thank you!

Hi Nicola! How does the flavor profile of this mango custard tart compare with the mango panna cotta that you mentioned? In your opinion, which one has a fresher mango taste?

Do the large amount of egg yolks overwhelm the mango flavor in the mango custard tart at all?

I'm planning to make a mango tart this weekend for the long holiday in the US and deciding whether to fill it with your mango custard or mango panna cotta. I'll be using tinned kesar puree if that makes a difference. Thanks a ton!