I’ve been thinking a lot about peaches and nectarines this week. Each year, there’s a week where the stone fruit in my local shop suddenly changes from rock-hard to juicy, from solid baseballs to perfect globes with just the right amount of give. The fruits look heavy with juice and ready to burst. But there is always one question that hangs over me. Are you team peach? Or team nectarine?

For someone so invested in the peach v nectarine debate, it seems rather cruel that I should be allergic to both. I’m not sure why I got dealt this hand in life, but many things I love the most are also things that I’m allergic to: Being outdoors (London hay fever, nothing quite like it, is there?), Cats and stone fruit. Now, these aren’t ‘stab me with an EpiPen and get me to the hospital asap’ sort of allergies, so for that, I am lucky. But they are runny-eyed, itchy lips, tingling throat kind of warning signs that may have made my ancestors think twice about chowing down repeatedly.

I touched on this debate briefly in last year’s “perfect peach tart”. On the subject of peaches v nectarines, I suggested the only difference was the fuzzy skin and left it at that. But isn’t part of being human the ability to go back and look deeper? To get some real answers?

Like so many things in life, the best way to get an answer is to go back, right back, right back to the very beginning. And, of course, we’ll end with a recipe to celebrate all of this peachy/nectariney goodness: My peachy choux! Crisp choux buns filled with peach mousse, topped with whipped ganache and macerated peaches. But as you’ll find out in the newsletter, these could just as easily be nectarine choux, if that’s your jam. Look at these beauties:

A short history of the peach

Peaches have been genetically traced back to China in 6000 BC. It’s a time so far in the past that, beyond major volcanic activity and landslides, there are only snippets of everyday human life. But there are pieces of evidence indicating humans were cultivating and enjoying the *literal* fruits the world had to offer, from the fossilised peach stones suggesting cultivating and farming in China to cheesemaking equipment in Poland, eel-smoking in Indigenous Australia to wine-making in Tbilisi.

In China, where the fruit originated, peaches are a long-standing symbol of immortality, or at least the desire to live a long life. In Chinese mythology, a banquet for the deities was held every 6000 years. Here, the eight immortals would feast on peaches to ensure their everlasting existence. With those credentials, it’s no surprise that China is the biggest grower of peaches in the world, producing some 11 million tonnes per year.

From China, the peach spread westward to Persia. From here, it was gifted to the Romans and received its botanical name, “Prunus Persica” (Present From Persia). It then made its way to Europe, thanks to Alexander the Great, before eventually reaching South America (via Spanish explorers) and finally to America (via English colonists).

Since peach trees take some seven years to fruit, planting these trees was always an exercise in patience and delayed gratification (though not as long as the 6000 years the Chinese deities were said to have waited, seven years is still quite a lot.)

So, if English colonists introduced the peach to America, does that mean… Peaches… were grown in the UK? You know, the place where the weather looks like this in July?

Yes, my friends, it turns out that peaches were grown in the UK. Peaches so good that, according to the diaries of William Penn quoted in the Annual Report of the Secretary of the State Horticultural Society of Michigan, Volume 18 in 1889, the peaches in the US were “not inferior to any peach you have in England” suggesting that peaches were pretty darn good. These were likely grown in ‘Peach Houses’, glass fixtures in walled garden kitchens in stately homes. These giant greenhouses would supply the house (and the wealthy family within) with exotic fruits which would impress visiting guests.

But the most famous British peach of all, the ‘giant peach’ of ‘James and the giant peach’ fame, was never destined to be a peach at all. According to Roald Dahl, his story was originally centred around a giant cherry. So although peach trees can be grown in the UK, whether they fruit (or whether that fruit ripens) is another story entirely.

While UK peach crops may have been abundant in the past, the changing climate means that British peaches are on a comeback tour. Though rumours about their return have been swirling (via supermarkets and small suppliers alike), I’m yet to see them widespread. Which, on account of the impending climate doom, is probably a good thing on balance? Though you may associate peaches with hot weather, it’s the contrast between hot and cold that makes for good blossoms.

Many plants, including peach trees, need ‘chill hours’ (yes, this is actually what it is called) which refers to a significant period - which varies between trees - of cold to come back strongly in spring. How cold and for how long? Depending on the fruit, between 0-7c and 50 - 1000 hours. If you hate winter, just find your inner fruit tree - without the cold weather, you won’t be able to spring back as strongly once things warm up.

One thing worth considering is whether the peaches of yesteryear Britain are anything like the dream peaches that we love so much now. Through mass farming and intricate cultivating, we’re now recipients of hundreds - if not thousands - of years of genetic crossing, tweaking and perfecting of fruit varietals. This leads us beautifully to the peach and nectarine question.

Peaches v Nectarines

Nectarines also originated in China. Starting as a genetic mutation that turned peach skin from fuzzy to smooth, this favourable characteristic was widely bred, so much so that it flourished into its own uniquely recognisable variety. The name ‘nectarine’ means ‘nectar-like’ or ‘of nectar’ and was first used in the UK in 1616.

But should we see peaches and nectarines as sisters, as in pink lady apples vs granny smiths, or as individual species? Having had some spirited conversations in the last few weeks with insistence (on both sides) that peaches and nectarines are identical, save for the skin, I decided to find out more.

The intertwined history of the nectarine is complex - the nectarine/peach records are not well kept. One Charles Darwin did note that nectarines would (apparently) spontaneously appear on peach trees and vice versa. To make things even more complicated, I’ve had reports that nectarines were marketed as a plum-peach hybrid which is utter rubbish.

So, when did the peach family tree fork off and split the hairy with the hairless? It's been claimed that the peach, with its fuzzy skin, is a fine example of ‘survival of the fittest.’ The fuzzy peach skin provided more defence from insects, sunshine, wind and all the environmental barrages you can think of. The smooth-skinned fruit, known now as nectarines, was more susceptible to these adversaries. Though the history is murky, it seems likely that the smooth-skinned nectarine was brought back to life by ‘modern’ (4000BC) farmers rebreeding this characteristic into the species. Many reputable sources cite that the nectarine and peach are genetically identical (or ‘similar’).

If I had to call it right now: A nectarine is a type of peach. A peach is a peach. And if you still need convincing, you can always trust the clues in botanical names - Peach is “Prunus persica” while nectarine is “Prunus persica var. Nucipersica”.

Within this family, we have subvarieties, like the flat peach, blood peach, nectavigne, etc. Unlike apples and pears, which have famous varieties and cultivars (e.g. Williams, Comice, Conference etc. for pear), peaches weren’t afforded this luxury - we simply know them by yellow, white or flat.

It should be noted that varieties and cultivars are not the same - varieties are naturally occurring, while cultivars are selected by humans. And if you want to learn more about the cling stone vs freestone conundrum, I’d suggest clicking here.

The taste test

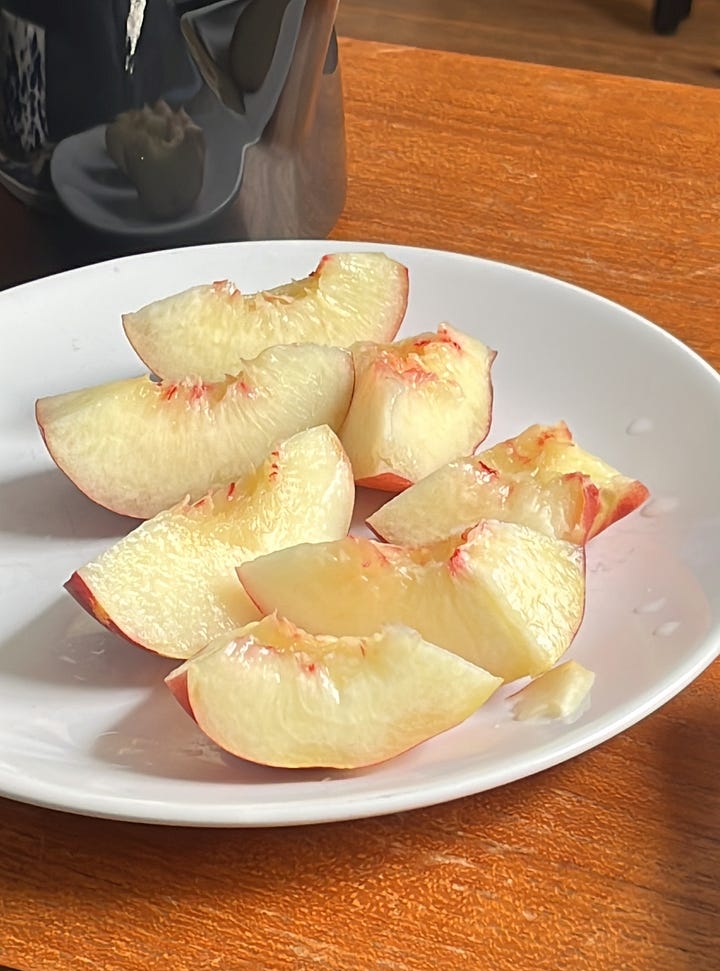

To see how different peaches and nectarines are once the skin is removed, I decided to run a blind taste test. With the fuzz out of the way, what were the defining characteristics of the peach and nectarine, and could they be told apart? I tried to get peaches and nectarines that felt similar ripeness and compared yellow round peaches/nectarines and white flat peaches/nectarines.

The results

So, the success rate was… mixed! Overall, the main differing characteristics seemed to be the difference in aromas, though my subjects noted that the two were incredibly similar.

Peach to her own: The flavour conundrum

Although nectarines and peaches began as twins, they have been bred independently for so many years that the varietals, which have succeeded enough to be mass farmed, have taken on unique features beyond the fuzz. Part of growing up is realising that modern farming doesn’t necessarily focus on growing fruit varieties that are the most delicious - it’s most likely a balance between taste and er… hardiness.

In my opinion, peaches take the journey from being tasteless to floral and sweet as they move from unripe to ripe. Conversely, nectarines are acidic and tart when unripe but move toward a piquant sweetness. Unripe peaches are lifeless, while the flesh of the nectarine has more tang. It’s possible that the denser, more acidic flesh of the nectarine might withhold roasting or poaching better, but I think much of this will rely on your individual taste.

Of course, I do not doubt that you could go to your local fruitseller and find me two varietals that refute all of this, but this is the rule I live by. For more acidity, go for nectarines and for more floral, subtle juiciness, go for peaches. White peaches will be the choice above yellow for the most floral and subtle, though I do also find they are the most disappointing. I build up a very flattering taste profile of white peaches in my mind but find the ones available in the UK usually miss the mark.

So, go forth, taste! See if you can taste the difference, and what notes you recognise between the yellow/white/peach/nectarines. And let me know where you lie on the nectarine v peach debate.

Peachy choux buns

Makes 8–10 buns