Kitchen Projects #003: Pasteis De Nata

Hello!

Welcome to the third edition of Kitchen Projects, a recipe development and cooking journal by me, Nicola Lamb. I’m a pastry chef and recipe developer and bakery consultant based in London.

Thank you so much for subscribing - I’m so excited to share this space with you.

When it comes to food (especially on Instagram!), you usually only get to see a perfect final product and none of the glorious trial and error that comes before it. This newsletter is all about giving you behind the scenes insight and, in turn, the confidence to try things, even if it doesn’t work out exactly how you planned. Spoiler Alert - it probably won’t work out exactly how you planned.

Part toolkit and part love letter to food, I’ll take you on the journey of a specific dessert or dish. This week it’s all about Pasteis De Nata aka Portugese Custard Tarts.

If you haven’t already subscribed, you can do so here.

And if you’re enjoying this then please, share it with a friend!

Love,

Nicola

ps. Substack is always telling me these emails are TOO LONG! So I can never include quite as many images and GIFs as I’d like. Once this goes out, I’ll add more GIFs/pics of tins etc to the desktop or website version so you can check back here soon for more visuals

Wanna make Pasteis de Nata? Nata problem.

Every city in the world has its own unique food performance, a show of pure skill honed and passed down over generations. You know what I’m talking about: the pasta-rolling nonnas of Italy; the soup dumpling machines in Hong Kong (I’m looking at you Din Tai Fung*); the pastrami guys at Katz deli; the noodle pullers of Beijing and those crepe magicians in Paris... I even felt the same wonder the first time I saw one of those bratwurst chopping devices in Berlin.

In Lisbon, it’s the nata! Oh the nata, that magical pairing of crisp pastry and sweet, oozing custard. I was there in 2018, with a Google map exclusively made up of Pasteis De Nata bakeries, where I’d park myself by the bakery windows to catch the show. With my nose pressed up against the glass (sorry bakers), I would stare as they lined hundreds of tins at unbelievable speed. I’d gawp as the custard was deposited and whisked away to the deck oven, immediately taking the place of a freshly baked and bubbling batch, leopard spots and all. My mouth would have been hanging open in amazement if it hadn’t been filled with custard.

I have absolutely nothing bad to say about any of the natas I tried, but I have a particular soft spot for the flair of the Pasteis De Belem pastries and of course the Mantagaria ones are outrageous too. Proper golden goo.

Since going to Lisbon every time I have a nata craving isn’t practical, I’m fortunate to have some pretty great natas on my doorstep, too. My first gooey nata experience was at the dimly-lit and now closed ‘I love Nata’ in Covent Garden where, apparently, they used to fly their natas in from Lisbon. The other nata hot spot, also sadly closed, was undoubtedly Taberna De Mercado, whose custard tarts provided an impossibly satisfying squish (I’ve heard that the pastry chef behind them supplies A Portugese Love Affair on Hackney Road, who also do the most amazing outdoor grill/barbecue sardine situation in the summer months). Cafe de Nata and Santa Nata in central London also look like they’ve got the goods, made in-house and baked fresh every day.

Right, so now that I’ve talked up the professional spots and have really amped up my imposter syndrome… it’s time to get onto the recipe. Oh, and here’s this week’s playlist.

*P.S. BTW, just to clarify… Din Tai Fung is Taiwanese and XLB does not originate in Hong Kong (its origins are in the Jiangsu province), but I just wanted to be true to my personal travel experiences. My travel bucketlist 10000% includes Taiwain. Dream.

I don’t like to start these projects off with a disclaimer… but with natas, I feel like I have to. First off, I am not an expert in natas. Until last month, I’d never made them before. I am simply a HUGE fan. This newsletter is a result of obsession. Secondly: of course natas are achievable at home. But they are tricky. You need a freakishly hot oven, among other things, to achieve those supermodel leopard spots and for the pastry to cook through quickly. And, although I hate relying on equipment for anything, having proper sized tins does make a difference.

A note on sweetness

Let’s be real for a moment. Natas are tooth achingly sweet. I set out to try and reduce this as much as possible whilst recreating the smooth and unctuous texture.

The natas you get in Lisbon, and in specialist places like Santa Nata, are permanently gooey. These natas also tend to have lighter brown spots, rather than very dark ones, suggesting a lower milk content. There’s going to be a difference between those and the kind that I’ve developed for ‘at home’ eating, where I have drastically reduced the sugar.un

The oozing goo is a result of 1) a high proportion sugar syrup 2) using very little yolk 3) using a very small amount of starch (less needed as there is not much yolk to prevent curdling) 4) using just enough milk to ensure the natas brown. To achieve this, your sugar % is in the range of 30%, which is also why the cinnamon flavour (the sticks are boiled in the sugar) is so pronounced. This is what gives you the liquidy centre!

For this recipe, I’ve tried to get the best of both worlds. I tested some yolk heavier recipes and loved them. They set up firmer throughout the day but that’s worth it for the mouthfeel and reduction in sweetness.

You can probably tell from these caveats that I was pretty anxious about making them myself. I mean, how could I possibly make a pilgrimage-worthy level nata? I’m afraid to tell you… I still can’t. But I’m happy! Let’s break down the components, shall we?

The pastry

Traditionally, natas are made with margarine or lard. I’ve watched loads of YouTube videos and, judging by the shocking yellow on show at Pasteis De Belem, they definitely use margarine. The natas at Mantagaria, however, are much paler which makes me think they use butter. I prefer the flavour of butter so I’m going to stick with that. Although marg or lard might give me a crispier finish, my goal for the natas is to maximise flavour.

The nata pastry is very simple with just four ingredients: plain flour, water, salt to make a dough and then fat (in our case, butter) gets folded in. To make it easy to work with, both during the lamination phase and the shaping itself, I decided to go for 50% hydration.

When it came to the butter I started with 50% of the flour weight. The first time around, I thought this was good. But on my second look at the dough I wanted more definition and flakier layers so upped it to 60%ish by adding a sneaky soft layer before rolling up. On baking, this made the natas both crunchier, flakier and more golden. Winner.

Getting the butter into the dough

There are two camps when it comes to getting your butter into the dough. On one side you’ve got camp “spread”, a traditional method which involves smearing soft butter onto the dough and then performing the folds. The second is camp “lock in”, which involves using firmer butter and a traditional method similar to how you’d approach a croissant or making puff pastry.

From more YouTube stalking, it appears the spreading method is more old school and perhaps better suited to soft squishy margarine. In the end, I decided to fuse the old and new school and finish off my pastry with a bit of spreading action just before rolling up.

However you’re doing it, the important thing is to work fast and work tidily. This gives you the highest likelihood if getting that lovely spiral on the base of the nata.

The custard

The first recipe I tried out was great but just... too sweet. The custard behaved (it puffed up in the oven and coloured beautifully) but there was something not-quite-perfect that I wasn’t satisfied with.

Guys. To tell you the truth, I went almost crazy testing this custard and my teeth began to hurt by the end of it. I’m going to tell you all about it. To date, I have tested around 29 custards with minor variations on starches, sugars and overall formulations

These ranged from custards with high yolk content with with firm wobbles, to inedibly sweet puddles that never really set. I even stumbled across a copycat perma goo style custard (though I’m not publishing it atm! It is MENTALLY sweet!)

My custard took on two areas of obsession.

Area of obsession #1:

The taste and texture

I wanted to figure out how to get the absolute best mouth feel (was it sugar? Fat? Starch?!) and flavour whilst drastically reducing the sugar. Turns out, you have to have an extremely low quantity of egg yolk in your recipe to achieve the perma-goo that we associate with natas. This, however, comes at the expense of sweetness. Personally, I want a tart that is rich with egg yolk, even if it does set up more at room temp rather than staying forever gooey.

Let’s breakdown the ingredients:

Sugar (and water)

A high proportion of sugar definitely contributes to an oozing texture and mouthfeel but natas can be OTT. I wanted to reduce the sugar down as much as possible (for the sake of sweetness) without losing the goo. We’ll go into the role of sugar syrup in the next section btw.

Sugar is also where the subtle flavours are added – cinnamon sticks and peels are boiled in the syrup giving that wonderful citrus and spiced taste. So if I was reducing sugar then what should I replace it with? Butter? Cream? More milk?

Yolks (fat)

Yolks thicken at around 80c and also contribute to the texture as well as being one of our main sources of flavour. However, yolks set FIRM so if you’re looking for an oozing centre then you have to reduce the quantity of yolks. This however results in a reduction in mouthfeel and flavour which I wasn’t willing to give up. When it came to fat, I wondered whether I should be expanding my horizons into double cream, or butter (like Nundo Mendes does?) or are the yolks enough? More on that below.

Dairy (main body, flavour and a bit of fat)

Milk, the good blue top high-quality stuff, makes up the main body of the nata custard. I spoke to a few nata fiends who suggested I might want to include double cream. I tried this but found that the custard became unstable. Same for butter – fat from dairy was simply splitting out. I was comfortable with relying on yolks for mouthfeel. It’s the milk solids that give you that burnt top, rather than the sugar (shout out to Mandakini at Smitten who pointed this out to me!) which is why milk is such an important component in getting the nata just right. Having a high % of milk also means you get lots of burnishing and dark spots which also helps counteract the sweetness, giving your pasteis an extra dramatic dimension

Starch

You need a decent amount of starch in the recipe, otherwise this would be the most depressing way to make scrambled eggs. You’ve got two options here: cornflour or plain flour. I tested flour-only recipes and cornflour-only recipes, as well as flour majority vs cornflour majority but the best results were always using a mixture of both, with a slight favour to cornflour. A warning - it is potent so a little goes a long way.

Cornflour alone was far too jelly-like, but definitely gives you the smoothest texture. The addition of flour gives it enough structure without being bouncy. Ultimately, I decided to reduce the overall % from 5.5% to 3.5%. Having run a number of tests, that was more than enough to hold all the liquid. It’s the combo of starch and yolk that impacts the final texture, especially once it gets to room temp.

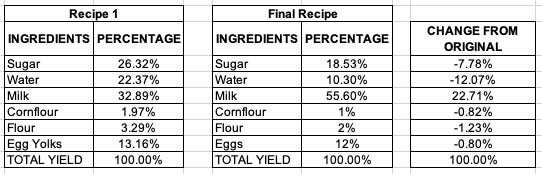

So here you have it, my percentage breakdown. I haven’t included the many many many formulations that I tried in between, but here you can see what I moved around in pursuit of sugar reduction without losing all the other wonderful things that sugar has to offer.

Area of obsession #2

The method

I mean, how much of a difference does a sugar syrup make? Do I really need to go through that whole process? Or can I just whisk the sugar in like I usually do for other custards?! Or just use creme pat, for that matter?

Classically, nata custard is made by combining sugar syrup with starch-thickened milk before finally mixing in the yolks gently. That was something I always understood to be true and had never questioned. Does making a sugar syrup really make a difference to the final product? Couldn’t I just make a creme pat? Should the yolks be cooked til thick, too?

I set out to test this and, surprisingly, these ‘small’ tweaks made a huge difference in the final products. Well, huge if you’ve been staring at custard all day.

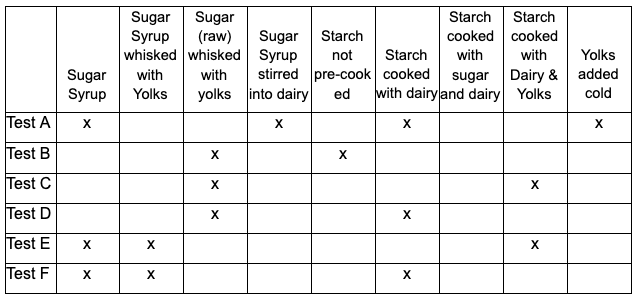

The nata custard cooking method test matrix

Instead of going through the tests one by one, i’ll rundown my overall findings from these experiments.

Pre-cooking the eggs & milk with the starch (like using a creme pat) makes a gorgeously creamy custard but it ended up quite gelatinous, too. The downside? It souffles like mad and then falls significantly, leaving a sad dipped middle. I loved the texture but the dipping wasn’t going to cut it for my perfect custard.

I also tried not cooking the starch at all; Rather than returning the dairy to the stove and letting it thicken before baking, I just combined and whisked it all in. This led to a thin, lean quiche-y looking custard that didn’t have a good mouthfeel and just looked a bit… gross?

One of my raw sugar tests actually exploded on me. This was test C (if you’re following along with the table) – I whisked the sugar with yolks then thickened the water (usually used to make the syrup) and dairy with starch on the stove. After 8 minutes in the oven, the custard exploded. Why? I wish I knew. Perhaps I’m introducing too much air when whisking the yolks which, in turn, expanded too explosively in the oven.

My final conclusion is both satisfying and a bit annoying: the classic way? Totally the best. Taking the sugar to syrup stage (over 105c, where you have evaporated approx 20% of the water which is why it is thick and gloopy when cool) must significantly stabilise the mixture. It’s this thick gloopy texture that makes natas… natas!

Given the short cooking time of the natas (sheer intense heat) you need your custard to be stable. Starch is a great stabiliser but the sugar also helps a lot. On a molecular level, the sugar and starch interrupt the egg proteins which would otherwise immediately set and scramble.

By gently folding or whisking the egg yolks in at the end you’re also limiting the amount of air you introduce thus encouraging a thick, dense custard rather than an explosive one.

Baking those Natas - the set up

The key to getting those burnished tops and crisp pastry bases is HEAT. Natas are traditionally baked in a deck oven. A deck oven has heat from both the top and the bottom radiating through the hot stones. You can also set the deck to have different temperatures at the bottom and the top, giving you more control of the bake.

Get your oven onto MAX (whatever that is) and let it heat up for at least 45 mins. You’re also going to want to get a pizza stone or at least put a tray in there to heat up with it. This is going to give you the intense heat that you need to help get a crisp base.

My initial thought was to fake a deck oven – two baking stones on two racks with enough space in between for a tray of natas.

Unfortunately this didn’t actually work out the way I wanted. The top baking stone was actually blocking heat from getting to the natas. This, however, does not mean that it won’t work for you! Every home oven is different and there will be a lot of personal trial and error for you to figure out where the hottest part is and what really gets the heat up.

During my trials, I was also warned not to over fill due to potential oven explosions but actually, you can fill it up quite a lot! I would say 5/6th is ideal, as long as your pastry doesn’t shrink too much.

I spoke a lot about natas with the aforementioned Mandakini of Smitten. She gave me a super fab tip - spray your natas with water when they come out the oven for that sheen! To be honest, it doesn’t change the natas radically but it is quite fun.

Baking those Natas - the timing

The longer you bake the natas, the more the custard will bubble and expand which means the more it will drop when it comes out the oven. It’s sometimes a tradeoff between getting the pastry cooked and risking the custard over cooking. If only we all had 300c deck ovens at home. I really wish I did!

The tins

The perfect nata tin is 7cm wide, 1.5cm deep (diagonal length is 3cm) with a 4cm base. It’s made of a thin metal that easily conducts heat – crispy base central!

The tins are going to be the first hurdle to jump for a lot of us. I ordered a few online, none of which were quite right. They still made good looking natas, but if you’re really looking for supermodel natas then you’re going to have to do a little searching. I was lucky enough to borrow some tins from a friend who picked them up in (sorry…) Lisbon.

I have tried this recipe using cupcake tins - it’s okay. They just aren’t the perfect shape. You’ll still get decent natas. Please just check your tins are safe at high temps though. You really shouldn’t take non-stick surfaces too hot - Teflon breaks down in a seriously bad way once it goes too far north of 200c. So, PLEASE, proceed with caution.

If you are heading to Lisbon anytime soon, head to POLLUX! They stock lots of sizes.

Okay. Time for the recipe!

NOTE: As of October 2024, this recipe has been updated. What I’ve changed:

-Using just cornflour for ease and lowered amount as increased fat content with cream

-More flavourful syrup, slightly increasing the sugar (3%) - if you prefer a less sweet nata, simply reduce the amount of syrup up to 10%-15% by weight.

Ingredients

Dough Recipe - Makes around 25-30 cases, approx 15g each.

230g plain flour

120g water

3g fine salt

125g butter

+ 20g soft butter for spreading on the roll-up

Custard Recipe - Makes enough custard for approx 20-24 natas.

Syrup

225g sugar

110g water

1/2 lemon, peel

1/2 orange, peels

2 cinnamon sticks

1 vanilla pod

Custard

165g double cream

400g whole milk

20g cornflour

100g egg yolk

290g syrup from above

For maximum flavour, I recommend making the sugar syrup the night before and allowing the flavours to infuse. It might crystallise slightly, but you should have enough to use in the custard.

Method - Dough

Measure the dries into a bowl

Pour in the water and mix together. It will appear dry at first but once it has made an approximate dough move it onto the table. It’ll come together sooner than you think!

Knead for 7-10 mins until very smooth

Wrap and put into the fridge for 30 mins to rest

Now it’s time to laminate the butter in. Firstly, cut your COLD butter into pieces and put into an approximate square or rectangle shape. Fold the paper around and start bashing and squashing it into shape

Once it is pliable you can start rolling back and forth on it. You’re aiming to make this block as even as possible. You can aim for approx 15cm x 20cm but don’t worry too much

Take your dough out of the fridge and press it into approximately the same shape as your butter block

Roll over the four corners on the dough so you have a cross shape, ensuring the dough is still fatter in the middle

Put your butter block in the middle of your dough and fold the crossed flaps over the top to enclose it completely

Now roll the dough to three times its length (approx 40cm) and then fold like a letter (aka a ‘single fold’)

Turn it 90 degrees and repeat - roll it to three times its length and then fold like a letter

Wrap your dough and let rest for 20 mins

Now it’s time to roll up your dough! Roll out the block until it is around ½ cm thick and approx 35-40cm x 20cm

Spread the soft butter in a thin layer all over the dough with the palate knife and roll it up tightly

Stretch the last cm to make it a bit thinner before pulling and sticking it onto the dough. This will make it easier to shape into the tins later

Chill for at least 1 hour or up to a day. It will oxidise slightly after 24 hours

Method - Custard

Put sugar, peels and cinnamon into a pan, followed by the water

Bring to the boil. If you have a sugar thermometer we are looking for approx 107c. This is the point that you have evaporated about 20% of the water. If you don’t have a thermometer, set a timer for 1.5 mins once it has reached a proper boil

You also have the option to infuse your milk with lemon and cinnamon, too, for a more pronounced flavouring. If you want to do this, simply bring the milk to the boil with additional cinnamon sticks and peel and then cover for 1 hour (minimum) to infuse before continuing with the recipe

In a saucepan, hisk the cream and double cream with the starch off the heat. Heat until smooth and thick - it will look a bit like double cream or condensed milk. You want to see 1-2 bubbles.

Off the heat, whisk in your egg yolks followed by sugar syrup. P

Pass custard through a sieve into a jug, so you can pour it easily into your moulds. The custard is quite thin. Cool completely before using. Can be made 3 days in advance.

Putting it together and baking

Get your oven pre-heating to MAX and put your pizza stone - or tray - into the oven to warm up. This is essential to getting the bases of the natas cooked

Remove your dough from the fridge and cut 15-20g pieces. Place these into your tins and allow to warm up to room temp for 15 mins

NB. The best way to ensure a flaky edge & neat finish is to line the tins whilst the pastry is at the correct temperature. You want the dough to be soft and squidgy and moveable.

Wet your fingers! This is also essential. Using your thumbs, smooth the dough up the edges of the tin trying not to touch the dough that will make up the rim. You don’t want to accidentally squash the layers at the top. You want the dough to be a bit thinner on the sides than it is on the base and the rim. It takes a lot of practice to get these right and I’m not sure I’ve nailed it yet, to be honest

Return your cases to the fridge for 20 mins or so to rest. This will help minimise shrinking

Fill your cases up to almost full - 5/6th. In my tins, this is approx 30-35g of custard

Bake for 8-10 mins, keeping the oven at max. The tops should souffle and be dark in spots and the pastry should look crisp. Depending on your oven, you may need to bake for longer or move your tray around during baking. My oven is insanely hot in the back left hand corner so I have to move it around to bake evenly

The longer you leave the custard in, the more the custard will bubble and expand and lift…. and then potentially fall later. It’s a trade-off you have to make whilst baking natas at home in ovens that aren’t hot enough to get it all baked super fast.

Allow to cool slightly before eating. Add more icing sugar or cinnamon on top, if you like

Eat within 24 hours

I loved following your journey of the Natas on instagram and now reading all the details is a treat. I've never had Pasteis de Nata and I don't have an excuse anymore since I'm at a stone's throw away from Portugal. Always wanted to visit and now I have an even better reason to go visit. In Bilbao, where I am from, we have Pasteles de Arroz, which funnily enough doesn't have any rice in it and it's really similar to Pasteis de Nata. I ate them all the time while growing up, along with bollos de mantequilla. This newsletter reminded me of my childhood and those pasteles de arroz. Can't wait to try some pasteis de nata. Great read ✨

It's funny that this showed up on my substack feed today. But my partner and I tried baking it yesterday using a recipe from allrecipes.com. At 550F, our oven caught fire!

Had to quickly extinguish it and call the fire department. I think we everyone pointed out, reducing the temp and cooking for longer or more importantly, baking it outdoors is the way to go.