Hello and welcome to this very exciting edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

Today I am handing over the reigns to Kitchen Projects resident preserving expert Camilla Wynne for a deep dive into Marmalade and it’s rich, golden history. I love how citrus is harvested in the winter. I always think of these jewels as a little wink from the heat of last summer, like a simultaneous reminder of the seasons past and a promise of good things to come.

Over on KP+, I’m thrilled to be sharing the recipe for a legendary Marmalade Ricotta Cake by Nichola Gensler, co-founder of Little Bread Pedlar. It’s part way between a cake, a frangipane and a cheesecake, and I can’t wait for you to taste it! Click here for the recipe.

Kitchen Projects is 100% reader funded; By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter and get access to baking Q&As, extra content, new recipes, community chat threads, and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month:

Love,

Nicola

A Marmalade Primer

by Camilla Wynne

“I got the blues thinking of the future, so I left off and made some marmalade. It’s amazing how it cheers one up to shred oranges and scrub the floor.”

-D.H. Lawrence

For many marmalade makers, this time of year heralds an annual ritual, a true act of ceremony: glorious simmering pots of citrus and sugar. This feeling was nearly lost to me beneath the grinding wheel of commerce after running a preserving business and spending so many years making it for sale in large quantities. Happily, after a few years of recovery, I once again rejoice each time I concoct my first batch of marmalade of the year.

When I teach a workshop on the art of marmalade, I aim to transmit some of this reverence but mostly spend my time trying to convince people that they can fit this ritual in into their harried everyday lives by breaking it down into bite-size pieces (which you can!). After all, it’s something to even have time to properly scrub the floor, much less first make a mess of it making marmalade.

That, or I’m trying to convince people to try marmalade at all! Bitterness is the most challenging of flavours. I had always thought this was because humans had evolved to avoid bitter poisons, but actually, 25% of the population has a gene that makes them particularly sensitive to the taste (perhaps they are more evolved?). Fortunately, in marmalade, the bitterness is tempered with a judicious amount of sugar. Either way, I mustn’t have the gene, as I concur with handsome Spanish chef Adoni Luis Aduriz, who proclaimed, “Bitterness is the richest and most intellectually satisfying flavour that exists.”

But what is marmalade?

The simple answer is a sort of jam but using whole citrus fruits, peel and all. But, of course, the evolution of marmalade has been a long and winding road. Almost all of what I know of it comes from the excellent Book of Marmalade by British food historian C. Anne Wilson; a signed copy from Alan Richardson’s collection (courtesy the wonderful vintage cookbook store Rabelais) has been a prized possession for years.

Much like a jumbo pâte de fruits, for centuries, marmalade was pureed and cooked to such a thick gel that it was molded in wooden boxes and served in slices, mostly as a dessert at the banqueting tables of those who could afford such luxuries as sugar and imported fruit. Over the centuries, marmalade has been considered a medicine, served at the end of the meal to facilitate digestion and prevent excessive drunkenness (ha! the health benefits of sugar, indeed), and even prescribed by doctors to treat common ailments such as colds. It’s been considered an aphrodisiac, with a batch famously gifted to Mary Queen of Scots when trying to conceive (though it contained many unusual additions, such as gold, ambergris and tail of newt). And, finally, it became the breakfast item we know today, though not without controversy.

It was reportedly the Scots who began to add more water to the mixture, rendering it spreadable and consuming it at breakfast in lieu of the traditional dram of whisky, much to some breakfasters’ dismay. Suffice to say there were some very aggrieved letters to the editor at that pivotal time. However, as marmalade consumption increased and new varieties of citrus became available, the market offered an abundance of flavours as well as textures, at least for some. Thick-cut marmalade was considered the stuff of men—also known as Oxford cut, it was created for the dons of the university at a time when women were barred from attending. Fine shred was considered suitable for ladies, children, the elderly and infirm. Fortunately, today one may cut it however one likes, and I find it varies not only by personal preference but by citrus variety—and never by gender.

True orange marmalade is considered by most to be that made with the Seville orange, a sour variety and the first to arrive in Europe. A culinary rather than eating orange, Sevilles have a richly flavoured skin, thicker than the navel variety, as well as a highly inconvenient amount of seeds. They are sour as lemons (and thus a fun substitute in desserts like lemon meringue pie or posset). Their season, however, is relatively short—a matter of months (this is true of many citruses but because we import the more common varieties from all over the world, it can seem as if they’re always in season). And that’s if you can find them at all where you live! The first time I made marmalade, back near the turn of the century, I used a can of Mamade brand prepared Seville oranges when I couldn’t find them fresh. Already cooked and shredded, one simply adds sugar, boils and pots the stuff. Frankly, it’s pretty good, especially if you reduce the sugar a bit, and I appreciate that it makes Seville marmalade so accessible, both geographically and physically. But, like D.H. Lawrence, I crave the meditative ritual of transforming raw fruit into marmalade.

The deal with Sevilles and what to do with seeds

Though Seville may be classic, almost all citrus makes excellent marmalade, though they aren’t to be treated exactly alike. All citrus fruits are relatively high in pectin (which is what makes marmalade gel), but as a general rule, the thicker the skin of the fruit, the higher in pectin. Indeed, the pith is where most of the pectin is to be found, though I long laboured under the assumption that a good, if not equal, amount was to be found in the seeds. Then, tired one day of meticulously separating the seeds and boiling them to make a sort of pectin stock (not quite willing to emulate food writer Alan Davidson, who famously left them in), I simply chucked them… to no consequence. From that day forward, I ceased to meddle with the seeds, as I’m always looking for ways to streamline the process in hopes that it will lure more people to the practice. Truly, it’s not a chore but a balm for one’s soul!

Welcome to the whole fruit method

The least chore-feeling method of all is the whole fruit method. Listen, there are plenty of ways to make marmalade, with different ones working better for different fruits or personal preferences. Some are, in my opinion, needlessly complicated—multi-multi-day processes that use some fruit just for pectin stock before discarding it; no, thank you. Others, like the sliced fruit method—which involves slicing the fruit raw, soaking in water overnight to soften the peel and extract pectin, then cooking until soft before adding sugar—produce a more refined, jelly-rich marmalade. But the most quick and dirty entry point into the art of marmalade is whole fruit. It’s for lovers of peel, the ratio to jelly being high.

An overview of the marmalade process

Weigh some citrus and pop them in a pot of water in which they can float freely. Cover and bring to a boil, then turn it down to medium to simmer until soft, generally an hour to an hour and a half, which happens to be enough time to watch an episode of prestige television or even a film. Before bed, turn off the heat and let the fruit cool in the water overnight.

The easiest way to slice the cooked fruit is by halving and eviscerating all its juicy contents. To make life easy, do this into a food mill or mesh sieve set over a bowl. That way, it’s easy to separate the juice and flesh, which we want, from the membranes and seeds, which can be discarded. The food mill will accomplish this with a few turns of its handle, while you’ll need to employ more elbow grease to push the flesh through the sieve yourself. Then, slice the peel as thin or thick as you like (or use a tiny cutter to make shapes!), then mix with the reserved juice and flesh, 100% of the initial weight of the fruit in sugar and 100 grams of lemon juice per kilo of fruit.

Do I really need that much sugar?

100% of the weight might seem like a lot of sugar but is actually quite modest for marmalade, which can call for up to 300% sugar! To my taste, 100% perfectly balances the bitterness and acidity of fruit like Sevilles, but you might want to reduce it slightly for sweeter fruits like tangerines. Keep in mind, however, that the sugar also helps the jam to set by binding with water molecules, thus making space for pectin chains to form, so you don’t want to reduce the sugar dramatically, especially with a thinner-skinned (aka lower pectin) fruit. The lemon juice is technically optional but helps to balance the sugar and activate the pectin (although too much acidity can do the opposite, so don’t go increasing the quantity).

A note on maceration and the question of use by dates

If you have the time to spare, this mixture can benefit from a night of maceration on the counter, dissolving the sugar and imbuing the peel. Then, in a heavy-bottomed pan, wider than high for maximum surface area to facilitate evaporation, bring the mixture to a rolling boil nearly over maximum heat (start a little lower to dissolve the sugar if you haven’t macerated). Once the setting point is reached (not using a thermometer but best tested with a teaspoonful on a plate in the freezer for 2 minutes—it should wrinkle when prodded), ladle into sterilised jars (at least 20 minutes in a 250°F oven) nearly to the brim, then seal tightly with new lids and invert for 1 to 2 minutes. Leave the jars unmolested for 24 hours before checking their seals, labelling and storing for… up to 25 years?!

That’s right, while we give a best-before date of 12 months to most homemade preserves, marmalade is unique because many people believe it improves with age. With time it will become firmer, darker and richer. I tend to prefer it after one year of aging. Famously, a jar was found with a group of explorers who had disappeared 25 years previous (and, sadly, perished). But when some brave soul dared to sample the vintage marmalade, it was declared “positively ambrosial.”

The world of alternative-citrus marmalades

Seville season being short, the good news is that citrus freezes admirably, so if you’ve spotted some at the grocer’s but haven’t got the time just now to make marmalade, pop them in the freezer and just set them straight to boiling whenever you do.

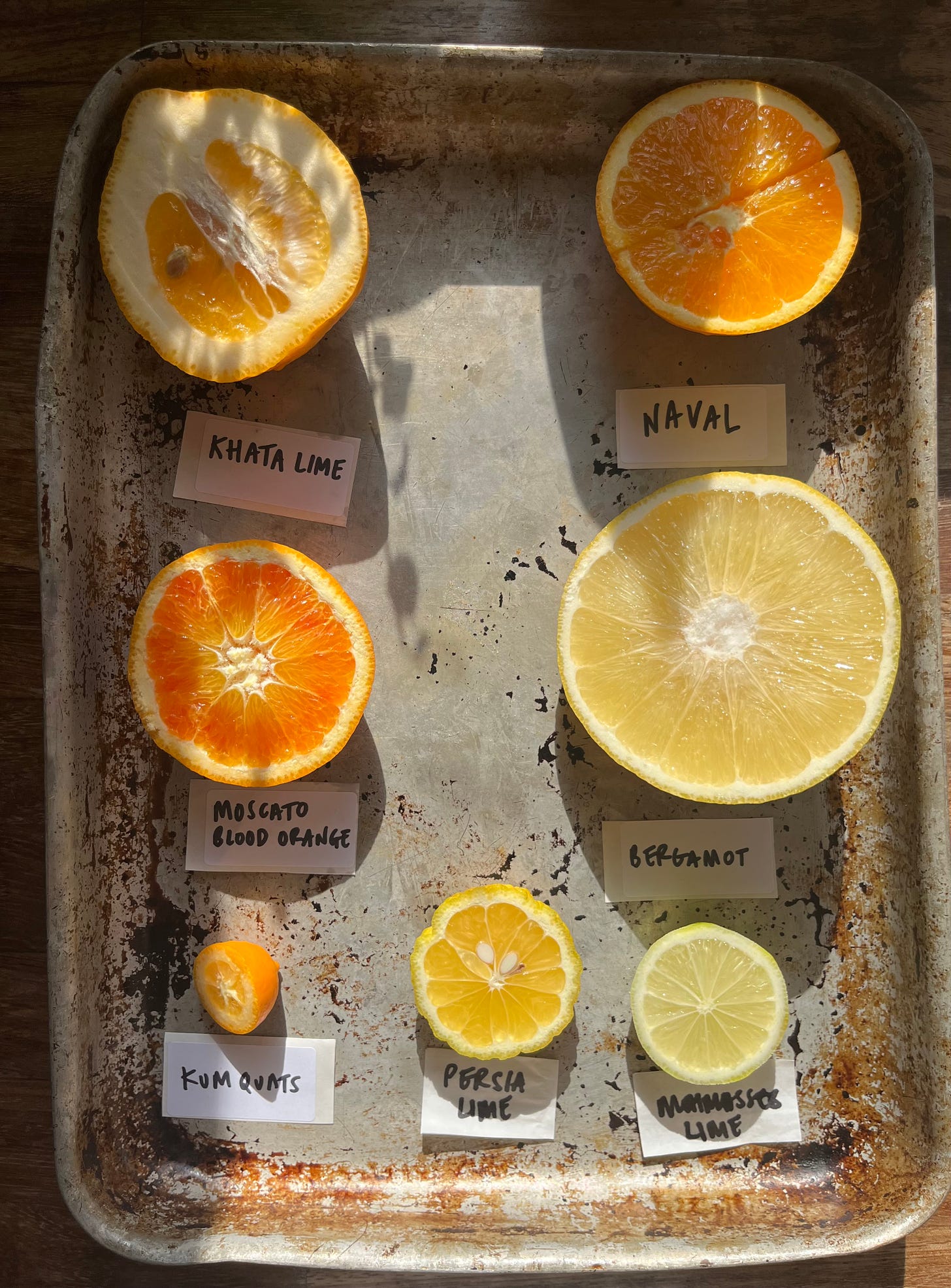

While Seville is my absolute favourite, the whole fruit method also works well with grapefruits in particular, as well as thinner-skinned citrus like clementines and tangerines. And while I generally prefer not to make marmalade fromby eating oranges like navels or Cara Caras, mostly due to their lack of acidity, they do bring a nice orange flavour to a mixed fruit marmalade along with lemons, grapefruit and perhaps clementines. From there, the permutations are endless: sub in some brown sugar for white—or honey (always by weight); steep tea, coffee, herbs or spices in your bubbling pot; throw in a handful of dried fruit, candied ginger, nuts or cocoa nibs; or add a big splash of whisky or another spirit before potting.

As to which fruits are unsuitable for the whole fruit method, limes are at the top of the list. They make nice marmalade but absolutely need to be sliced and soaked before cooking. Boiling them whole results in little leather footballs that will challenge both your knife and your teeth. You’ll also want to steer clear of any citrons, such as etrogs or Buddha’s Hand, which are fleshless and need a different approach that shreds their zest and makes a jelly stock of their pith. Pomelos, similarly, have thick skin and relatively dry flesh, making them a bad whole-fruit match. On the other end of the spectrum, kumquats are tender enough that they don’t need any pre-cooking before becoming marmalade, and boiling them whole could cause them to break down.

Fortunately, there are enough citrus varieties suitable for this method that you’ll have no trouble creating your recipe to make a ritual, filling your home with the heavenly scent of cooking fruit and buoying your spirits during the colder months. And if you’re neat about it, you’ll scarcely need to clean the floor afterwards.

Whole Fruit Seville Marmalade

Day 1: 10 minutes active, 90 minutes inactive

Day 2: Approx 1 hour active

Makes 5 half-pint (250 mL) jars

1 kg Seville oranges

100 g lemon juice

1 kg white sugar

Method

Put the oranges in a pot large enough to hold them in a single layer. Cover them with water, cover the pot, and bring them to a boil over high heat. Reduce the heat to medium and allow them to simmer, covered, until they are very soft, about 1 ½ hours.

Let them cool a while in the water (preferably overnight), then cut them up.

The best method for this is to halve them, then scoop their insides out and run them through the small disk of a food mill or else push them through a sieve, although the latter takes more elbow grease. Either way, this will keep all the delicious flesh and juice but remove the seeds and membranes.

Quarter the emptied halves, then slice the peel as thick as you like. I favour ¼-inch (roughly 1/2cm).

Combine with sugar and lemon juice, and let macerate for at least 15 minutes at room temperature or up to 1 week refrigerated. (If your oranges aren’t very juicy you might want to add up to 120ml water to help dissolve the sugar.)

Prepare clean jars by placing them upside down on a rimmed baking sheet in a 120c oven for at least 20 minutes.

Transfer mixture to a wide, heavy-bottomed pot or preserving pan. Heat on medium- high, stirring frequently.

Boil hard (though be careful - the jam is very active and may spit) until the setting point is reached. This is when a teaspoon of jam placed on a cold plate in the freezer for three minutes will wrinkle like a silk shirt when pushed gently with a finger. The marmalade will be darker and feels thicker when stirring. This took my recipe tester around 20 minutes to achieve.

Editors note: Check this KP for more signs your jam is done!

Pour into prepared jars to within a 1/4- 1/8-inch (1/2 – ¼cm) of the rim. Wipe the rims if necessary, seal and invert 1-2 minutes.

So now you’ve got Marmalade! What now? Well, here’s a few ideas.

Marmalade Ricotta cake

This marmalade ricotta cake by Nichola Gensler - it’s somewhere between a cheesecake, frangipane and a cake, laden with creamy ricotta, the nuts giving an intriguing texture that I can’t stop eating. Click for the recipe

Marmalade brown butter cakes

Another citrus treat made with the auspicious golden orbs that are tangerines, perfect for tea time. Plus a guide to citrus fruits! Click here for the recipe

Ultimate citrus layer cake

A tried and tested (I’ve made it three times now) and such a crowd pleaser: Blood orange, olive oil cheesecake layer cake with salted vanilla buttercream. Click here to make it.

Pink grapefruit and toasted almond marmalade

Camilla Wynne’s perfect childhood breakfast in a jar! Click here for the recipe.

Kamut & Poppyseed Muffins

Another beauty by Camilla. Made with golden kamut flour and the grapefruit jam, they make an excellent breakfast or snack, boasting wholegrain fiber and a little almond protein.with marmalade. Click here for the recipe.

You've made my day! I'm so glad you've found a love of marmalade and are now surrounded by Paddingtons!

I was never much of a marmalade fan until I tried Camilla’s recipe and method. Now I can’t stop! I have her book Jam Bake (thanks Nicola for the introduction) and took the marmalade workshop, both brilliant. Now our house has a marmalade shelf, and friends and family have all turned into Paddingtons. Thanks, Camilla, for sharing your secrets and giving us sunshine in January!