Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

A few weeks back at the beginning of my pavlova testing, I asked ‘What are your pavlova issues?’ via Instagram and you guys delivered. From cracking, to sugar content, to chewy vs. fluffy, I HAVE ANSWERS. Lots of them.

In fact, there are so many, I haven’t been able to include all of them in this single newsletter. So, I’ll be sending the full Q&A and troubleshooting out for my KP+ subscribers.

Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. So, if you’d like to support the writing, get access to extra content, including the full Pavlova breakdown, and community chat threads, click below:

Alright, let’s deep dive

Love,

Nicola

A mountain of a meringue

As my mum said (after watching me make a LOT of meringue this week), “Is there really any point making this yourself?” and the answer is YES!

Rather than the recipe itself, today’s KP is more about technique and I’ll be sharing a lot about the wonderful world of meringues based on YOUR questions!

So, as requested by you guys via insta, the Pav-woe-va topics are as follows. The topics in italic are available on KP+, click here to read.

The VIQ: CHEWY OR SOFT?

Mixing issues

When should I add sugar to the whites?

My meringue is always gritty no matter how slowly I add the sugar?

How long to whip the whites

What speed to whip the whites

Can I over whisk the egg whites?

I think Pavlova is too sweet. What is the minimum sugar needed to maintain the structure?

Should I be using cornflour/vinegar/water

Shaping the pavlova

Bake issues

Bake temperature

How long to bake it for?

Weeping meringue

Spreading in the oven

Beading / spots of sugar on meringue surface

How to adjust time for different shapes?

Not knowing how long is long enough to keep in the oven after baking

Post bake issues

My pavlova is cracked

My pavlova collapses when cooling

Pavlova sticks to the paper / the base is too soft

Tastes and smells like egg

Humidity issues

Storage

Today’s newsletter is a Q&A format… let’s do it!

VIQ: Chewy or soft

Before we get started, we gotta talk about this whole t TEAM MALLOWY vs TEAM CHEWY thing.

The mallowy pavlova is the classic pav - a crisp exterior with a fluffy middle. But I know there are people who like it a bit more toothsome (it was 50/50 on my Instagram poll!) so let’s discuss how to adapt it.

Sugar makes the pavlova mixture strong and stable, and is responsible for that super hard shiny crust. I found that as you reduce the sugar or increase the brown sugar (it has more moisture), the final result is a chewier, with a more fragile, shattery crust. Basically, the more ‘free water’ there is in the base recipe, the chewier the meringue is.

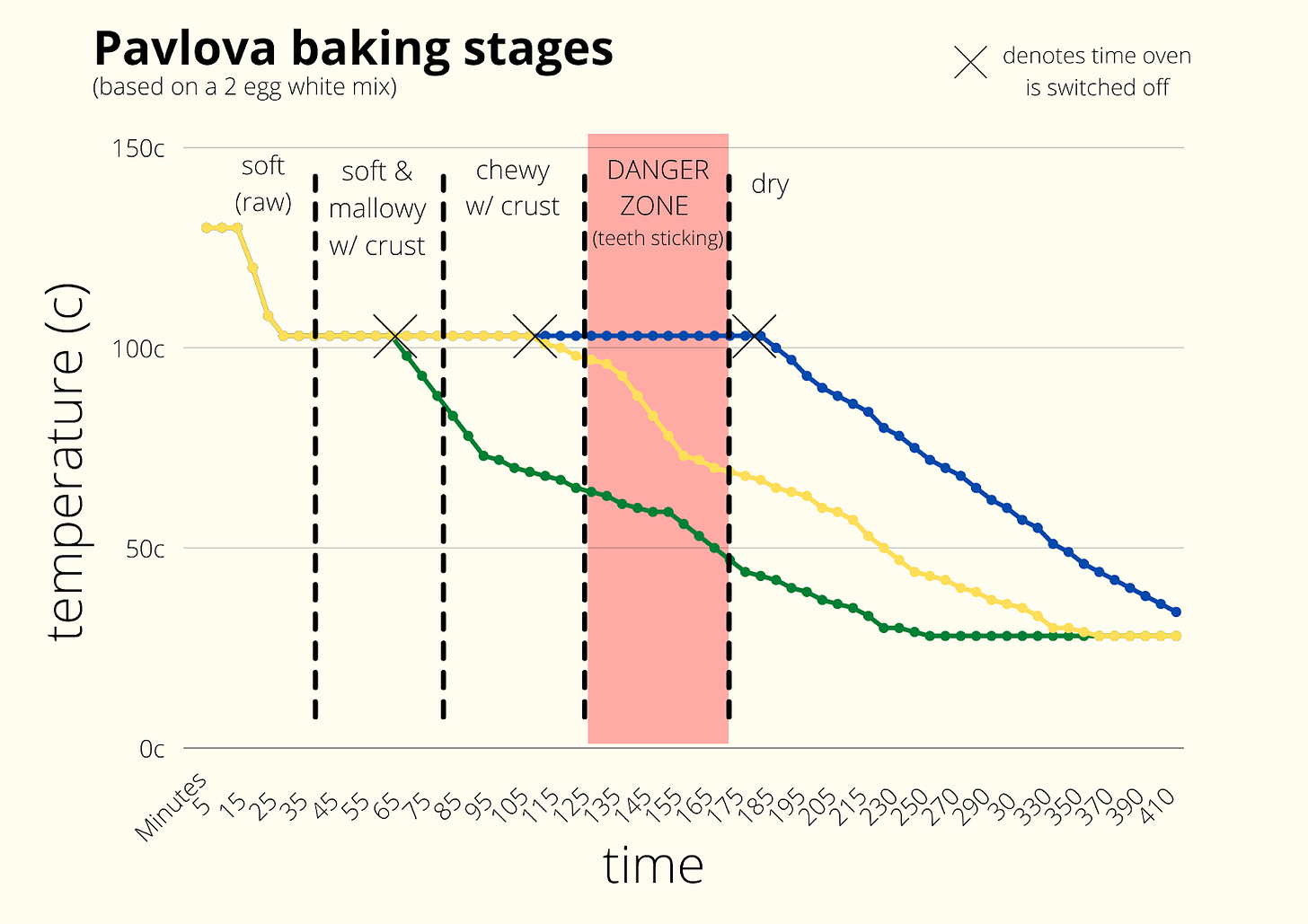

The other way to achieve a chewy meringue is through the bake time. When you bake your pavlova, it is going through a few stages as the heat slowly penetrates into the centre of the meringue. Let’s discus

The stages of meringue baking

It starts as a completely soft raw meringue but quickly becomes marshmallowy all over with a soft-to-the-touch crust.

Next, it has a crisp crust with a fully marshmallow inside

After that, it’s a crusty edge with a soft/chewy inside.

After that it’s the danger zone aka stick-to-your-teeth type texture

Finally, we reach fully baked and crisp all the way through

Judging the chewy factor can be hard - you need to stop the cooking somewhere between marshmallow, teeth sticking dangerzone or fully cooked. Without sticking a fork into the meringue AFTER baking, it can be hard to judge. So, the easiest way to game getting either a mallowy or chewy pavlova is through the shaping.

A mallowy pavlova is easy to achieve with a tall, thick crown shape, as its more difficult for the heat to penetrate the thick meringue walls. Therefore a chewy pavlova suits a low, wide disc shape better. as you can get a better concentration of heat around the whole meringue.

By focusing on the shape, you don’t have to change the bake times listed in the recipe today - you could bake a tall crown in the same oven as a low-wide disc and get both a mallowy and a chewy meringue in one bake!

The deal with brown sugar (Read on KP+)

Mixing issues

When should I add sugar to the whites?

We do have to be a bit of a goldilocks here. If you add the sugar too early, you hinder the egg white protein's ability to unfurl to the maximum potential. Too late, the water-loving sugar starts to get greedy with the structure and begins to leach water from the already stiff structure, destabilising it.

Here’s the stages up to when I start adding the sugar at ‘soft peaks’ - it looks a bit like the foam you get from a hotel coffee machine cappuccino, if you know what I mean. The eggs have enough structure to just about stand up, but aren’t at all dry or clumpy.

Sugar added too late/too early resulted in a less stable meringue for me, which in turn resulted in cracks and weeping as the structure broke down in the gentle oven.

My meringue is always gritty no matter how slowly I add the sugar

When making a meringue, you really want to make sure the sugar is totally dissolved. Sugar particles are hygroscopic and unattached molecules invite in water from the surrounding environment.

I’ve been here. Maaaany times. And I have checked - it does actually matter if your sugar is all dissolved. For a small pavlova, mixing until smooth is relatively straight forward. But the larger the pavlova, the more challenging it is to mix in a home KitchenAid.

To test the theory of ‘add the sugar SLOWLY’, I added a tablespoon of sugar to whisk egg whites every 45 seconds until it was done. This took around 15 minutes. After such careful adding, I was sure I was going to be greeted with an ultra smooth, grit free meringue. NOPE.

It was STILL gritty. So, although adding the sugar slowly is best practice, being so extreme about it doesn’t actually make a huge difference. The largest impact is from the length of time mixing. I find that I need to mix my meringue for at least 15-25 minutes (depending on the size) on a medium speed to achieve anything NEAR smoothness.

During this time, the heat from the mixer actually warms up your whites (as well as the room temp air being incorporated) and that warmth (see Swiss meringues) does help to incorporate the sugar. Don’t worry about overdoing it - as you’ll see below, it is nearly impossible to over whip a meringue and any negative associations are only a result of continuous whipping way beyond smoothness has been achieved.

Swiss meringues (Read on KP+)

How long to whip the whites?

The question of how long to whip the whites must be thought of instead as ‘what is happening when I am whipping the whites, and why?’. From this there are two major reasons.

The first reason to whip the whites is to incorporate air into the protein mesh of egg whites, which then is fortified with sugar. You are able to create a foam because when the proteins unfurl during whipping, half of the protein chain is ‘water loving’ (hydrophilic) and half are ‘water hating’ (hydrophobic). This allows them to create large chains as the hydrophilic part sticks to the water and the hydrophobic part sticks to air bubbles, resulting in the increase in volume. So, this means, first and foremost you need to whip the whites for as long as it takes to get a shiny, firm and bright white meringue.

The second reason you are whipping the whites is to incorporate and dissolve the sugar by agitating the mixture continuously. So, the length of time required to whip the whites is as long as it takes for the above to happen.

However, to put a time on it, I think at least 10-15 minutes for a small mixture (two whites) then increasing in at least 5-10 minute increments per additional egg white. The most effective way to test whether the sugar is dissolved is by rubbing a bit of meringue in between your fingers to check its dissolved state. If it hasn’t, keep mixing! And we’ll get on to ‘overmixing’ soon...

What speed to whip the whites

This follows on nicely from the above - to achieve a stable meringue with well dissolved sugar, I fully recommend whipping on a medium speed. On my Kitchen Aid, that means MAX 6/10, but usually sticking to 4/10. Going into gear 8/10 or 10/10 is asking for trouble. If you’ve made my genoise recipe, you know that creating a fine, stable egg foam is best done using moderate speeds. For the genoise, I recommend first whipping the eggs on high then followed by descending speeds, but for egg whites only I found it best to whip on medium speed from the outset.

Although whipping on high is tempting, air introduced so quickly is quite erratic and the protein network is filled with different size bubbles. These different size bubbles mean you cannot get a uniform foam which then leads to the foam breaking, either during the mixing process or in the oven. I’ll cover that next.

Can I over whisk the egg whites?

As I’ve said before, I’m not sure its *possible* to overwhip an egg foam when it has sugar in it - ie. it isn’t going to get clumpy or collapse.

I put this to the test - I whisked my egg whites for 50 minutes on medium speed and there was no visible difference to the mixture.

To push the eggs further, I increased the speed of the mixer to max and this is where I saw a significant change in the meringue - It became extremely stiff and shiny, so it didn’t deflate exactly, but it lost a lot of volume - it was almost sticky in appearance. It didn’t have any of the ‘textured’ look that *the entire internet* suggested might happen but it was definitely not right. And, on baking, the meringue cracked and weeped.

This confirms to me that you should whip your egg whites with moderation, paying most attention to speed rather than overall time spent. As you can see in this photo, it is visibly smaller than the other pavlovas I was testing:

Egg whites aren’t whipping up properly (Read on KP+)

Can I use boxed egg whites? (Read on KP+)

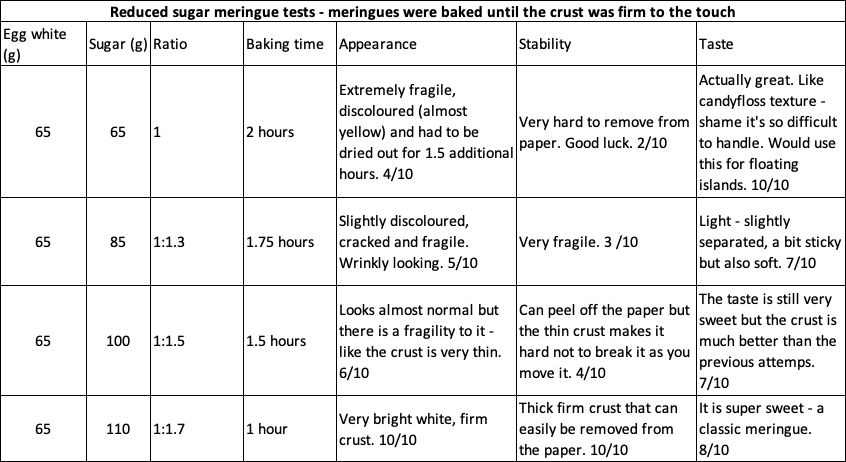

I think Pavlova is too sweet. What is the minimum sugar needed to maintain the structure?

This is a great question and one that I spent a lot of time testing!

Relative to other recipes, the pavlova recipe I’m sharing with you today has a low ratio sugar of egg whites - 1 : 1.7! Believe it or not, this is on the lower end of the spectrum but it is the minimum you need to get a crust that is bright white and stable.

Here’s the why: Rather than ‘reducing the sugar’, I’ve come to think of this process instead as ‘increasing the free liquid’ in the meringue. Basically, the less sugar you’ve got keeping the water busy, the more there is ‘loose’ in the mixture. As you increase the free liquid, the softer/chewier/more fragile your pavlova becomes. Sugar, as well as sweetening, fortifies the foam. If you whip egg whites alone, sure they’ll foam up! But the foam will disintegrate fairly quickly. Sugar provides the stability and structure needed to make a meringue that can hold its shape. As you decrease the sugar, you still get a beautiful foam but it becomes less bright white and becomes quite hard to work with - it has the texture of a loose, light shaving foam - almost piecey - and you start really struggling to get a well defined shape (also see: adding water)

As a result, the meringue becomes less and less stable and struggles to ‘harden’ or get a decent crust. Although the mixture can hold peaks and can be baked, it takes a long time to dry out (remember, lots of free water!) and it is also very fragile. It is really hard to move off the paper and it shatters and crumbles very easily. These meringues are also prone to attacks from humidity.

Here’s the results of my tests:

Although I loved the 1:1, it is so unstable that I think I could only use it for other meringue preparations - roulade could work (will investigate) and could be good for floating islands, as it yields a soft but slightly chewy meringue, like candy floss. The in between ratios aren’t really worth making because they are neither less significantly sweet nor any more stable.

To cut a long story short, Pavlova is sweet by nature. And you need at least a 1:1.6 ratio of sugar to get a bright white, stiff shell with a hard crust. My suggestion is rather than trying to reduce the sweetness of the meringue, create toppings and fillings that counteract the sweetness. I will never, for example, use sweetened whipped cream to fill it. This, to me, gives the perfect balance between flavours and textures.

Should I be using cornflour/vinegar/adding water?

Alright. Let’s talk add-ins!

Let’s start with acids

Here’s a quote from my previous Kitchen Project ‘HK Milk Tea Tres Leches’ to explain the why:

I looked to OG food scientist and hero Harold McGee to understand this more deeply: McGee has done a huge amount of research about the effect of copper bowls on egg whites - according to McGee, during the aeration process of egg whites several types of bonds are formed - the bond between the proteins (what we hear about a lot) but also bonds between sulfur groups. These sulfur bonds are unstable ie. prone to breaking down, so by whipping egg whites in a copper bowl (or indeed, adding an acid) you are interfering with these awkward sulfur compounds and thus making it more stable.

So YES! Acids are important. There is some discussion about *when* to add the acids and what kind (cream of tartar? lemon juice? vinegar?). My preference is white wine vinegar. I don’t find there’s any after taste and since it is usually only around 10g, it’s easier than squeezing a tiny bit of lemon juice. I’ve had good results adding the vinegar at the beginning of the mixing process and folding it in at the end and I can’t see any discernible difference. But ensuring its thoroughly mixed throughout is key. I achieved this via a liaison batter with the cornflour - our next topic

Cornflour

According to *the internet* cornflour helps keep your pavlova base chewy or marshmallowy but I personally disagree. According to Anneka Manning, the role of the cornflour is to “Cornflour stabilises egg whites during baking and prevents weeping by stopping the egg white bonds from tightening too much”. I sort of see the logic to this (is it like with creme pat? The starch thickens and holds liquid maybe?), though I’m not entirely sure. And I have used cornflour in Pav’s and *still* had weeping. So what gives?

What I do know is that a Pavlova baked with vinegar/cornflour vs one baked without and the one without was only slightly inferior in looks (see pics above) But more importantly, I found the pavlova baked without vinegar/cornflour actually had an eggy taste to it. That to me makes it worth including cornflour/vinegar every time from now on!

Although I’m still trying to understand the science on a foundational level, it’s worth including it to avoid any egginess, especially if you want to do a soft tall pavlova. I don’t think it would be as important for the low-wide chewy pav.

Water

I’ve seen recipes which ask you to add water to a meringue. Although this makes for a gloriously voluminous mixture, it is a bit unstable and makes the crust very thin and fragile and extremely prone to cracks in my experience - it also has an almost pearlescent look to it and there is a lot of separation between the centre and the crust. As mentioned before, “free water” has a major impact on the final meringue. I can’t recommend this, although it isn’t the end of the world if a splash gets in.

Making a nice shape

Shaping is an extremely important part of the pavlova process and not just because of aesthetics. When you shaping the pavlova, you are also ensuring that there aren’t air bubbles trapped in the mixture. You need to first shape the meringue into a solid mound and then go from there - if your meringue is really stiff, it’ll likely have craters of air throughout as you put it onto the baking tray. It’s your job to try and minimise this. Air pockets can later cause cracking as the unattached air bubbles escape through the crust as they expand.

If your meringue is correctly whipped then you should be able to reshape your meringue as many times as you need to to get a shape you are happy with. So, if you’re not happy, just mound it back into the middle of the tray and start again!

I have two main shaping methods. GIFs are in the recipe

The crown

I have looked at a lot of Pavlovas online and have to say I don’t really get the whole tall but flat Pavlova thing. I want my pavlova to have a decent hole in the middle (an on purpose one) so I can fill it with a LOT of fruit and cream. Scooping out the middle also means heat can penetrate mass and from more angles.

Finally, the crown is finished with some fancy looking swipes of the palette knife - just drag your palette knife through lightly. A lot goes a long way on these shapes. If you’re not happy with it, just smooth it all back over and start again.

My large pavlovas are around 8 inches wide, 3 inches tall with a 4inch crater in the middle. My small pavlovas are around 6 inches wide, 2.5 inches tall with a 3 inch crater.

Low wide

This is my ideal shape for a chewy pav - a low wide disc. You begin with a mound then slowly expand the diameter coax it into shape with the help of a palate knife to create a bit of a rim. You can even out the crust with a spoon to give it a bit of a decorative flourish.

Bake issues

Bake temperature

Rather than baking a pavlova, consider instead that you are drying out the foam slowly to encourage it to retain its structure as much as possible as the proteins in the white slowly coagulate and solidify, setting the foam forever! The air trapped within the protein network will expand slightly as it sets, but we are not trying to evaporate the water. A meringue does not change weight pre/post-bake like most things baked at a higher temperature.

The general pavlova consensus is this: Pre-heat oven to “high” - 120-140c fan - then either turn it down right away to somewhere between 80 - 100c fan, or leave it at the higher temperature for a period of time before reducing temperature.

I prefer the higher end of the spectrum, starting at 130c fan, holding for 10 minutes then lowering to 100c fan. This gives me a pavlova with a perfect crust. The “blast” of heat at the beginning allows the crust to set and as it gently moves down in temperature.

I took notes of the temperature inside the oven as it was lowered from 130c to 100c during a pavlova bake:

130c - 10 minutes

After 5 minutes - 120c

After 7 minutes - 113c

After 10 minutes- 108c

15 mins - 103c

One thing to remember is... All home ovens are different. What is working perfectly in my oven may not work perfectly in yours. If you have an oven thermometer, I highly recommend using it. I started my tests at home before taking the pavlova show down to my parents in Brighton. My mums oven, as it turns out, runs 20-25c cooler (but not *all the time*) which made for some interesting tests.

Manually adjusting the oven to keep it within the right cooking zone was a challenge but what I know is this: Some things are just out of our control! I promise to arm you with the best information I can, but you might have to do a test run if you have an important event coming up to see how your oven behaves.

If you know your oven ‘runs cool’, then adjust accordingly. If your oven runs hot, then reduce the start baking temperature by 5-10c.

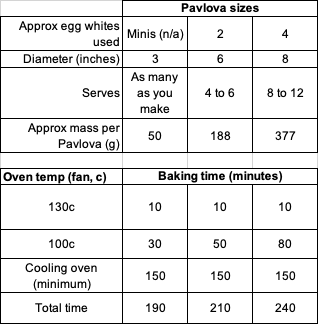

How long to bake it for and how to adjust for different shapes?

Here’s my baking times guide from the last week based on my oven (also using an oven thermometer, though a single probe can’t account for weird hot spots etc but I tried my best):

Remember, the chewy vs. mallowy is achieved via the shape in my method.

The most important part of the bake is by far starting it out at the higher temperature. Don’t skip this part. I struggled to get good results from Pavlovas baked at a constant lower temperature - they were much more susceptible to weeping and the crust/base was never as good.

Not knowing how long is long enough to keep in the oven after baking

Weeping meringue

Ahh, the weeping meringue. A tragic and oft seen sight. The clear liquid that can leak from a meringue is sugar syrup.

If your meringue is destined to weep, this is usually a result of an issue in the initial mixing. Whether your sugar hasn’t been dissolved properly (see notes on how to add sugar correctly and when to add the sugar), or if the structure of your meringue has been destabilised (see overmixing) then the strong mesh network of proteins, water and sugar will break down. Remember, meringues are a love triangle between sugar, proteins and water. If one has bonded more strongly than another, you will likely have problems down the line.

The other culprit can be underbaking - when you bake your pavlova, if you are introducing heat too quickly then the proteins coagulate too quickly, again, disrupting the strong stable structure, causing sugary liquid to leak out. The outside is then set but the inside, when reducing the heat, is not dried out adequately, leaving free sugary water to make a mess on your tray.

The final culprit is inappropriate storage. As moisture from the air returns to the pavlova and gets involved with the water loving sugar, it can begin to pool, creating more weeping situations.

Spreading in the oven

A little bit of spreading is natural. Your meringue is bound to change shape a little bit, but it shouldn’t be dramatic. In fact, it should be quite helpful - the messier more angular bits will be softened!

It’s worth remembering that meringue is used as a raising agent in recipes like chiffon cake - the trapped air expands during baking. So, meringue, if baked at too high a temperature, will lose its shape as air expands before the meringue is set.

If your meringue has been taken off too early and isn’t stiff during shaping, you will also see more movement. So, try to make sure that your meringue is at peak stiffness and glossiness.

Beading / spots of sugar on meringue surface

Ah, the sister of weeping. Beading is when small droplets of sugar syrup are pushed from the meringue during baking. This is a result of overbaking - if the proteins set quickly in heat, the sugar syrup will be pushed to the surface. It is often caramelised. There’s nothing you can do about this except take it easy on the bake next time.

Meringue is never bright white

Pavlovas need to be baked at a low temperature otherwise the sugar will begin to caramelise. On making a sugar syrup, the first hint of the palest golden comes at around 135c so chances are your oven is a bit hot.

As well as this, I found that the meringues with less sugar did not have a bright white sheen/crust! So don’t cut back on that.

My pavlova is cracked

OK GUYS: CRACKS - they happen. They just do. It has happened to us all. Basically, cracks are either a result of the air trapped inside the meringue inflating OR deflating. It goes both ways!

The cracking can happen during baking as a result of a few things - air pockets expanding too quickly during the bake, forcing its way through the crust. As well as this, if the mixture is very warm going into the oven, the air trapped inside is closer to a temperature that it will evaporate, again, causing rapid expansion/expansion which then causes cracks (this is what I discovered with a Swiss Meringue.)

Similar to this, if the pavlova cracks within the first 15 minutes of the bake, it’s because the oven is too hot. The crust is hardening too quickly before the middle has had a chance to expand so it bursts through. If the pavlova cracks at the end of cooking, its because it has been cooked too quickly and crust is too hard and is forced apart as the mallowy middle settles.

As well as this, the pavlova is quite sensitive to temperature changes. If the pavlova is suddenly exposed to cold air, mallowy centre may deflate quickly, causing cracks to appear on the surface, but this generally only happens if the crust already is too thick.

Basically - cracking is somewhat inevitable. But you can do your best to avoid it by keeping the cooking very gentle.

My meringue collapses when cooling

The meringue collapsing is a result of dramatic changes in temperature either during baking or after.

During baking, we slowly lower the temperature (see Bake Temperature and How Long to Bake) to encourage an ideal ratio between crust and soft centre. If the crust is set but the middle is not adequately set, it will separate as it cools and not have enough structure to hold itself up. As well as this, if the crust is too thick, it will crack and fissure as the pavlova settles.

A little separation, especially for a soft centered pav, is expected if you are shaping it into a dramatic crown shape, but as long as it is structurally sound then you’ll be okay.

Collapsing as it cools can only be solved by proper temperature management during the bake and after. See bake times and temp!

Pavlova sticks to the paper / the base is too soft

Ah, a culprit of under baking! For small pavlovas I don’t find this is an issue. But for larger pavlovas I actually like to bake them on a pizza stone or a pre-heated tray. For the pizza stone, I shape directly onto it and it retains enough heat to stay crisp. For the pre-heated tray, you can either shape the pavlova on paper then slide it onto the warm tray, or just double tray it. This will ensure a lovely crisp base every time. Again, paying full attention to the baking time is the key here.

If your pavlova is stuck to the paper, you can return it to the oven on a pre-heated tray and continue drying it out. If you don’t have time for that - I’ve done some emergency c-sections on pavlovas with a couple of palette knives. Just make sure you have someone to back you up!

Tastes and smells like egg

The only time I had this issue was when I made a soft pavlova without cornflour/vinegar. I don’t imagine this will be so much of an issue for a chewy pavlova, or a fully baked meringue, but for the soft centered pavlovas, which are very lightly cooked, it’s important to get out of this potentially eggy territory. I cover all things ‘eggy’ - the what, why and how in the peach creme caramel Kitchen Projects here!

Humidity issues

I’m so fortunate to rarely have humidity issues in the UK. If I did live in a humid environment, from what I’ve learnt from the tests, I would increase the sugar to create a stronger and firmer meringue, increase the cornflour/vinegar by 2% and I would not remove the pavlova from the oven until I’m ready to serve. You could move it into an airtight container, too, but keeping it in the cooking vessel is a better guarantee for success.

Storage

You can freeze pavlovas. In fact, a soft pavlova will get a lovely chewy texture so if you accidentally make a soft pavlova, just pop it into the freezer and rebrand it ‘frozen pavlova’ and you’ll be happy. For storage, you can happily freeze a pavlova but defrosting it can cause issues as they will absorb humidity from the environment. So, defrost in an airtight container or in the oven at 80c (fan) for 20 minutes or so until the have returned to former glory.

Fillings

Topping a Pavlova is one of most freeing and joyful activities. Usually I go for a using a classic unsweetened vanilla chantilly and berries, but you can really go wild. Poached apricots? Roasted peaches? Amaretti biscuits? Cherries? Sour cherries? Jams? Curds? Chocolate? Caramel sauce? Coffee cream? Rum raisins? YOU DO YOU! And don’t forget to tell me about it.

Pavlova recipe

I have not been too prescriptive with the toppings as you can put whatever you want in a pav, such is the magic of the beast! But I have included a guide of a classic pav that I made.

Small Pavlova (serves 4-6)

65g egg whites (2 large)

110g caster sugar

3g white wine vinegar

3g cornflour

Large pavlova (serves 8-10)

130g egg whites

225g caster sugar

6g white wine vinegar

6g cornflour

Filling suggestion

Large pavlova

600ml cream with the beans of 1 vanilla pod whipped to *THE SOFTEST* peaks (it should almost be running off the spoon still)

200g berries, macerated with 20% sugar, 20g lime juice and mint

200g berries, fresh

+ mint to garnish

I like to macerate half my berries in sugar so I then get some gorgeous syrup juices to pour on topSmall pavlova - halve the above

Method

Pre-heat oven to 130c (fan) or 120c (fan) if your oven is one of those aggressive ones

Whisk egg whites until soft peaks on a medium-high speed

Then lower the speed and start adding the sugar slowly, in small increments leaving a bit of space between - this should take around 2 minutes

Once it’s all in and turn the speed up to medium again. Set a timer for 15 minutes at least before checking if the meringue is at stiff peaks, is shiny and thick and that the sugar is dissolved. Rub the meringue in between your fingers to check. If not, continue whisking for 5 minutes at a time until combined

Mix the cornflour and vinegar together in a small bowl. When the meringue is ready, spoon a few tablespoons into the mixture and mix well - this is called a liaison batter

Pour/spoon the liaison batter back into the main meringue mixture and fold it / use the whisk to mix for 30 seconds until well combined

Shape your meringue as desired - tall crown (mallow!) or low wide (chewy!)

For small pavlova: Bake for 10 minutes on 130c (fan) then turn down to 100c (fan) for bake for a further 50 minutes. Turn off the oven and allow the pavlova to cool inside for at least 1.5 hours, ideally 3-6 hours, or overnight

For a large pavlova: Bake for 10 minutes on 130c (fan) then turn down to 100c (fan) and bake for a further 1hr20 minutes. Turn off the oven and allow the pavlova to cool inside for at least 1.5 hours, ideally 3-6 hours or overnight

Fill your pavlova with prepared fillings. BE GENEROUS. MAKE IT SAUCY! It’s best to do this just before serving for the chewy (it is THIRSTY and will take all the moisture it can get), or maximum 1-2 hours in advance for mallowy. You can make a further dent in your pavlova if desired to get more filling in.

I love your thoughtful instructions, I’m surprised you didn’t suggest putting sugar in food processor to make it superfine. I find this helps with the grittiness issue.

I made this today! As always, great recipe - I only had a tiny bit of weeping. The base didn’t stick but was soft - do you shape on one tray which you then place on top of the tray heating in the oven or do you transfer the pavlova itself onto the hot tray directly somehow without it collapsing?