Hello!

Welcome to another edition of Kitchen Projects. It’s so lovely to see you here.

Today we’re taking a big, gorgeous bubble filled jump into the world of bread: This super airy focaccia is one of my most requested recipes ever so I’m thrilled to be sharing it today with a deep dive into yeast, gluten. and all those good things.

Over on the KP+ this week, I’m so excited because my friend Jordon - a seriously talented chef who is currently making pasta at Burro e Salvia - has created TWO genius recipes to go along with this focaccia dough. Trust me, you want to be there. I’ve had a preview and it is truly magic.

Subscribing is easy and is only £5, so if you fancy supporting the writing as well as getting some extra content (more chat threads launching soon!) then click below:

Love,

Nicola

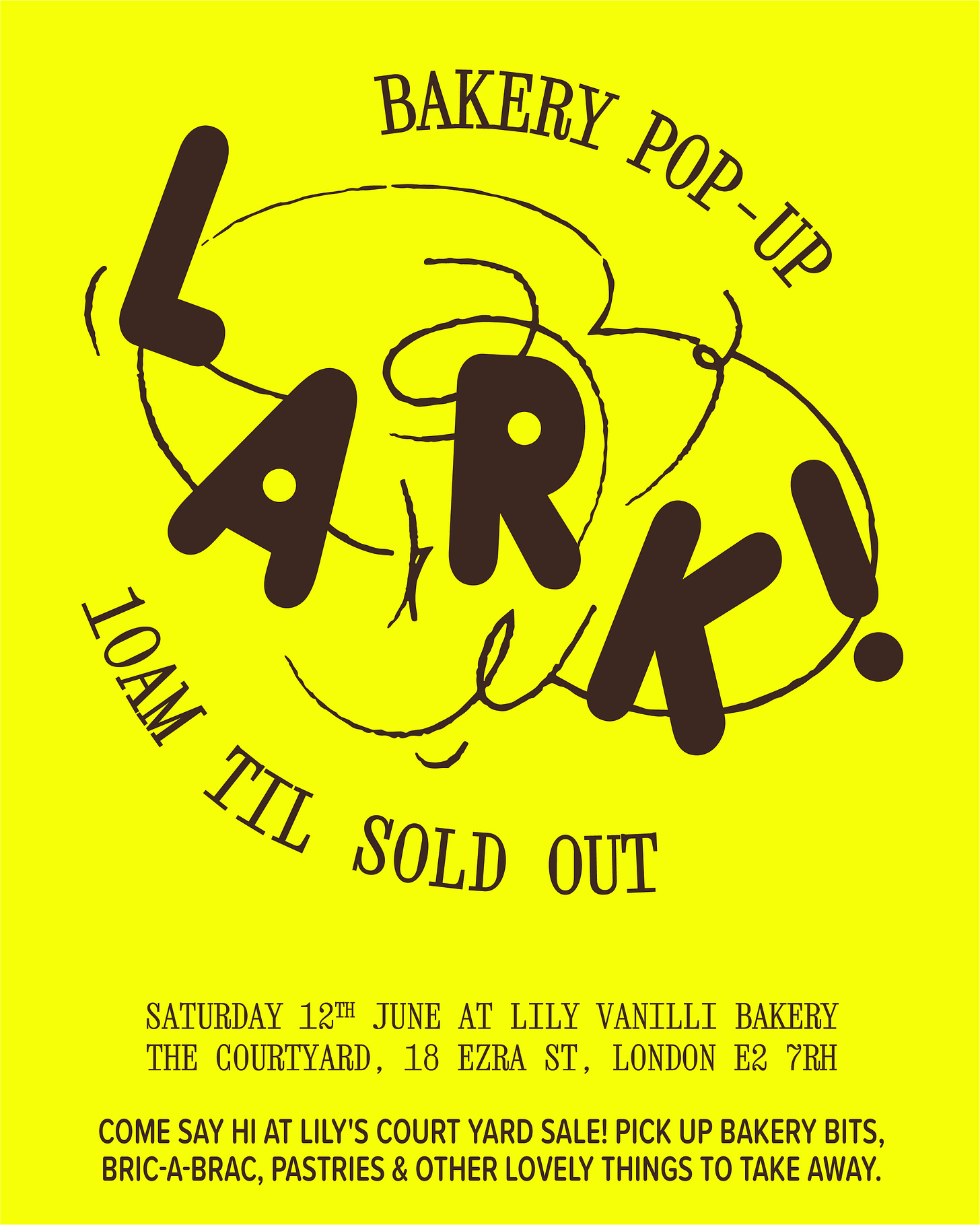

Introducing… Lark!

Before we get to this week’s newsletter, I wanted to share some news with you guys before anyone else... I’ve launched a brand new IRL baking project-baby: Lark!

Lark! was originally supposed to open in Scotland in a full-time location earlier this year. Long story short (I learnt a LOT and more on that another time), it wasn’t meant to be. So instead, Lark! will be a pop-up bakery instead, with an ever-rotating seasonal menu of treats and goodies, PLUS fun collaborations with other chefs.

The first ever pop-up will be next Saturday 12th June at Lily Vanilli’s bakery in Columbia Road from 10am until sold out! I’ll be announcing the menu on the @bakerylark instagram soon, so please do follow along the journey. Really hope to see you there.

BTW, the main Sunday newsletter will be on break next week as I’ll be in the kitchen prepping for the pop-ups. For my KP+ gang, I’ll be sharing a special recipe from the pop-up menu with ya so look-out for it!

A focaccia made of dreams

As we head toward summer of picnics and outdoor suppers, I think focaccia pretty much qualifies as an essential skill.

If you’re interested in bread but not sure where to begin, focaccia is a sort of home-run crowd-pleaser that’ll never let you down, especially with this method. Your friends and family are going to adore you even more.

I developed this focaccia a little while back with the sole aim of making it the most airy, juicy, delicious and bubbly focaccia ever.

To get it there, I started with a base recipe by my brilliant friend Stewart (follow him here). Stewart, a brilliant baker and KING of 2am fancy-ass omelettes (night shift essential) brought this super high hydration focaccia to my attention during our time together at Little Bread Pedlar.

His focaccia was always next level with it’s multi-step mixing process and long cold fermentation. And although it was already pretty much perfect, I decided to experiement with the base and add poolish - a pre ferment - to take the texture and structure even further. ALRIGHT, let’s go deeper.

So…. What IS focaccia?

Focaccias come in all shapes and sizes - you have the fine textured, cakey kind or the mad bubbly kind, which is more popular here in London. But no matter which you prefer, the most important thing about a focaccia is that it is rich with olive oil. And really good olive oil if you can.

Today’s Focaccia is the ultra bubbly kind and it is seriously wet. Adding hydration to your bread has become popular over the years, but it can make a dough very hard to work with. The best thing about focaccia is that you get to enjoy the fruits of an ultra hydrated shattering-crusted crumb without having to worry about the shape. We want it to be wild.

But for a dough to be able to take on that much hydration, you need a LOT of strength and Focaccia is extremely buff. We’re going to the bread-gym today, basically.

One of the things I want to achieve with Kitchen Projects is to add techniques (preferments, cold fermentation) to your wheelhouse that you can apply to ANY recipe. I want you to feel confident to split off part of your water and flour and pre-ferment it, to add a prolonged cold ferment, to play around a few different flavour building strategies. Even if your recipe doesn’t explicitly state it, I want you to feel confident to play around or adapt little parts of recipes when you see them.

Let’s make a bread

When you think about bread, the most important thing to remember is you are trying to balance gluten development with fermentation. AKA you’re trying to make sure you have enough structure to capture the gases produced by yeasts.

The nice thing about focaccia is that the goal is for it to be basically a liquid. That means you don’t have to worry about it being a bountiful loaf shape - you want it to lie flat and just be bubbly. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have to be well developed.

Focaccia has a low % of yeast, but a little goes a long way. Although the yeast will eventually colonise the whole of your bread dough, we combine a slow fermentation process (including cold proofing, which slows things down) to keep this in check.

Here’s a breakdown of the process/bread tactics we’ll be going through together that you can add to any recipe:

Poolish - aka a pre-ferment. We’ll be taking a portion of our water and flour from the recipe and mixing it with a little tiny bit of yeast and leaving it for 12 hours - the result is a bubbly, aroma filled mass

Autolyse - This is a technique where you mix your flour, yeast and water together (sans salt) and leave it for 30 mins to fully absorb and hydrate, building gluten as it goes. Although some bakers will say autolyse is when you mix just flour and water together (no yeast), we’ll be including our yeast today

Holding back the salt - During the autolyse, the salt is held back. Salt is a water hog so you’re allowing the flour to fully hydrate. As well as this, holding the salt back gives the yeast a chance to get going without salt retarding it

Stretch n folds - A gentle way to get involved with your dough - this bit feels so good

Cold fermentation - An exercise in strength and flavour building

Let’s talk pre-ferments

We had a little chat about pre-ferments during the Rhubarb Bun recipe (which, btw, you should DEF be making with strawberries now) and you may remember that pre-ferments benefit your dough on multiple levels: Head start on fermentation and flavour.

Today I am delighted to tell you about the poolish: A poolish is a wet pre-ferment. It is made with 100% hydration (equal water and flour) and a small amount of yeast. The (g) weight of yeast is less important than you think - it just needs to be enough to digest the flour in the poolish but not so much it’ll be OTT once you add it into the rest of the mix.

This is then left overnight to get bubbly and flavourful and then introduced into the dough. A poolish, in particular, is known for providing additional extensibility (stretching!) to doughs so is often used in croissants to add both flavour and ease for the laminating process. Basically, it will improve your bread massively with very little effort.

What’s the deal with yeast?

When formulating a bread recipe, thinking about what it looks like will give you an idea of how much yeast to use.

On the back of yeast packets and in bread recipes everywhere, 7g dry yeast to raise 500g flour seems to be standard - this is just over 1%-2% of the flour weight. That’s standard for anything from bread rolls to loaves.

For something flatter, like pizza or focaccia, the yeast content is much lower. According to the book ‘Mastering Pizza’, it’s anywhere from 0.02% - 0.05%.

However, this can be a bit confusing - an errant search on flatbread recipes on Google has recipes for pita breads and naan breads at 1.4% - much higher than the flatbread % from the pizza book. So what’s going on there?

TIME!

Many modern recipes are designed to favour speed. Irrespective of the final product, recipes are generally developed so that only an hour or two of rising (aka waiting) is required.

Even flatbread recipes (which clearly don’t need as much rising power as a white tin loaf) rarely deviate from the standard 7g to 500g ratio and simply cut the second rise short. You could comfortably slash the yeast weight in half without any ill effects - unless you count waiting around as an ill effect, of course.

So, to sum it up, it’s not so much about the amount of yeast (as long as there’s some) but how you handle it.

Understanding yeast vs. sourdough

To understand yeast %, we need to have a quick recap on what yeast *actually* is: A diverse microorganism.

Yeast is a fungi that digests sugar and, as a by-product, produces CO2, ethanol and ‘flavour compounds’. WTF are flavour compounds? Well, specifically, it’s a bunch of organic compounds like esters, aldehydes and alcohols. Non-specifically, it’s the things that make your bread taste like… well, bread. These compounds are aromatic and give bread the tangy and fruity notes we know and love.

But before we go deeper on that, you need to be able to sort your commercial yeast from your wild yeast and understand the differences there.

Commercial yeast aka the fresh yeast and dry yeast you can buy in the shop is a single strain of yeast. It was isolated, laboratory grown and tailored over the years to be extremely efficient in raising bread.

Wild yeast, however, does not play by the rules so much. Rather than just one strain of yeast being present, a sourdough starter will have a whole gang of yeasts, populated from the air around wherever the starter is being made. These yeasts just aren’t as reliable, efficient or speedy as their commercial counterparts. Fortunately for naturally leavened bread, it isn’t *just* yeast that is responsible for the raising when it comes to natural fermentation: A sourdough starter also contains LAB - lactobacteria.

These naturally occurring lactobacillus are also responsible for fermenting the dough and producing CO2 as well as being responsible for the ‘sour’ flavours associated with the bread.

In fact, when it comes to sourdough, LAB outnumbers yeast! But it’s that interactive effect of the yeast and the LAB that give a compounded effect of fermentation in the form of bread structure and flavour. That’s why sourdough bread has so much depth in it’s flavour.

We won’t be covering sourdough today, and instead will figure out how to get the best out of commercial yeast. Although it is fast and reliable, it does lack complexity. This is why bakers over the years have established techniques and strategies to coax flavour out of the fermentation process. Yes you can raise a bread in an hour, but are you really getting the best out of it? Life is always full of trade-offs, but flavour usually wins, right?

The journey of yeast

To understand its impact on flavour, it’s important to understand the transformational journey that yeast goes through during breadmaking:

Yeast is mixed into dough

The yeast begins to eat / process the sugars present in the carbohydrates (flour), it begins to create useful by-products for breadmaking...

As the dough is aerated during kneading, the yeast undergoes AEROBIC respiration because oxygen is present and it produces CO2 + water. The bread rises fast when it is undergoing this respiration but it isn’t as flavourful

When there is a lack of oxygen present, the yeast switches to ANAEROBIC fermentation, where CO2 + ethanol + flavour compounds are the by-products. It is bit slower but provides more flavour

As it respires / ferments, the gases produced by the yeasts are captured by the gluten network, creating a network of structure and airpockets within the dough

The higher the temperature, the more yeast activity there is and the more CO2 is produced (it rises more)

When the dough is stretched and folded or divided and shaped, these airpockets are redistributed or collapsed entirely (deflated). The yeast will continue to ferment and produce by-products and the bread will rise again as CO2 is captured in the gluten network. It will continue to do this until it runs out of nutrition and there’s nothing left to for the yeast to process, getting continuously more sour

Eventually, the yeast has produced so much ethanol that it can no longer function

Further to the above, a dough can be deflated several times and re-shaped before the yeast is no longer able to rise the dough. This article suggests upward of 10 times you can still have success (depending on the circumstances inc. environmental factors and temperature) but just because you CAN… doesn’t mean you should, ya know

How to favour flavour

So, from the list of actions by the yeast above, why not just add additional rises to your bread, knocking it back over and over again until the desired level of flavour development is reached?

Well, you could. But it’s more sensible to use some other tactics. My favourites? Pre-ferments and long cold fermentation!

As we’ll discuss in the poolish section below and in the rhubarb buns KP, pre-ferments provide a layer of flavour and jump start on strength-building.

Cold fermentation, however, and the reason why this focaccia takes 3 days, is a great lesson in both patience paying off and flavour. To understand this, we have to remember that yeast is a fungi and loves a warm environment and that temperature is really the only real thing that speeds up fermentation. Useful as it is if you’re in a rush to get the bread filled with CO2, it doesn’t favour flavour.

Cold fermentation will slow the yeast activity right down which is a good thing, because when the yeast isn’t going absolutely nuts digesting sugar and producing CO2, it is really helpful in a flavour creating process called the… wait for it… Alpha Amylase Reaction.

I know, it’s not a catchy name. But you don’t need to know it by name. You just need to know that it’s an action where complex starches are further broken down into sugars and flavours are made. Although this does happen if you just left flour and water on its own, yeast - when under control in a cold environment - can provide some useful enzyme action to coax those flavours out, and provide new dimensions for your bread.

Building strength

I know we’ve been through this before but let’s quickly recap: Flour contains proteins - Glutenin and Gliadin - that, in the presence of water, form gluten bonds. Gluten provides structure, shape and stretch to your dough. The presence of gluten allows a dough to be both elastic (holds its shape) and extensible (stretches). Although mechanically kneading the dough can help build strength in the dough and organise the gluten bonds, gluten will form very happily on its own. Here’s an excerpt from the rhubarb cream buns post from a few months ago that goes into the details:

“Flour – once hydrated – will immediately begin to form gluten bonds and, in a process known as ‘autolyse’, the enzymes present in flour will begin to break down the proteins which makes the dough really stretchy and developed. As the yeast processes the sugars, the CO2 expands which has the effect of very gently ‘kneading’ and stretching the dough. Cool, right?”

For today’s recipe, we aren’t going to totally leave the bread alone but we are going to be gentle. I personally love the folding and stretching process of the focaccia - it feels SO good to get your hands covered in olive oil and gently stretch the dough. While most of the gluten developing is happening without our assistance, we support the strength building with a series of gentle movements that are surprisingly effective given how minor they look.

When you’re stretching and folding you can try a few different techniques - as long as you are gently stretching the dough, it doesn’t matter! You’ll notice in the GIFs below I use a few techniques, from lifting the whole dough up out the bowl and rounding it in my hands, or by stretching and folding each corner of the dough until it is degassed, or performing a coil fold (lifting up in the middle and placing it back down on itself).

Getting the best texture

Cold fermentation is also useful in helping get the absolute best texture from your bread. Although your dough may look extremely hydrated and happy as-is, you’ll have to trust me that it goes up a level when it spends time in the fridge. Left for a prolonged period of time, the gluten is fully hydrated through autolysis creating an even stronger gluten network that provides an even more dramatic and noticably improved structure to your bread. Since we are shaping focaccia AFTER the cold proof, we get to benefit from that ultra strong gluten development and well-aerated structure aka bubble town.

Does this need to be a three day process?

Well that depends. You want to make a focaccia in one day? DO IT. But i’ll show you how it will change.

I made three doughs to demonstrate this. All were made with the same recipe, same number of folds and in the same environment.

#1 was made with an all-in method - everything mixed together all at once then fermented at room temperature and baked on the same day

#2 was made with a poolish but fermented and baked on the same day

#3 was made with the all-in 3-day full blown method - poolish, cold fermented then baked

Visually, the crumb of doughs 1 & 2 are similar - the blistering on the crust is least extreme in dough 1 - the dimpling doesn’t seem to move or expand during baking and you can clearly see finger divots throughout - it’s sort of flat, like volanic rocks. The crust is also quite dull:

Compare this to the light and airy crust of doughs 2 & 3. Although the internal structure of 1&2 are similar, the blistering (as well as the flavour) is seriously improved with the help of a poolish. The crisp is much thinner and crisper and the divots have expanded giving a more interesting terrain:

So, now we’ve discerned between the poolish and no poolish methods, it’s time to move onto the role of cold fermentation by looking at the internal structure. The improvement is significant with the cold fermentation! Just look at the difference in this crumb:

So, YES, the three day process does make a genuine difference and I’m not telling you to do something I wouldn’t always do myself. The poolish brings the flavour but the cold fermentation brings the bubbles and structure. I promise it’s worth it!

When to add olive oil

You know how when we’ve made sweet doughs together in the past, we wait to add the fat until some gluten development? That's because if added too early, the fat coats the flour proteins making it hard to create gluten. Some focaccia recipes have the olive oil added right at the beginning but I prefer to slowly fold it in throughout the stretch and fold process. This gentle method ensures the structure of the dough isn’t affected by the large quantity of oil but you’re still getting plenty of flavour in.

An oil enriched focaccia crumb is something of beauty especially when you’re doing something with high hydration - the crumb is both tender and chewy with thinly stretched crisp walls from the large irregular pockets of airbubbles - it’s a joy to eat.

Don’t forget to use good olive oil and don’t scrimp! I rarely scale the olive oil that I use for the focaccia, choosing to do it by eye instead. Though the full quantity is somewhere around 75ml-125ml, I just add olive oil when I can no longer see any! Once it's been absorbed by the dough, I just add a little more. It’s helpful for the stretching process, too, so your hands don’t get stuck!

The deal w/ salt

When you’re salting your focaccia, you have a few routes to go down. Salt doesn’t burn, but there are a few ways to get it on your bread.

The first and most obvious solution is just to err…. Sprinkle it on your bread pre baking, obviously. Classic. Works a treat. But there’s a couple of other techniques I've collected over the years if you want to step it up a notch.

Salt, applied pre-baking, doesn’t have the same diamond glint as salt applied after baking. The solution? Spritz your focaccia with water once it comes out of the oven and then sprinkle with salt. The water will evaporate on the hot focaccia so dw about it going soggy, but in the process the little diamonds of salt will stick.

Another solution is to create a brine, aka a salty solution that you cover your bread in - a watery, oily, salty mixture that keeps the bread moist and seasons it tremendously. You can read more about the technique here in a piece by the iminitible Samin Nosrat.

When it comes to salt, carefully consider your other toppings: Capers and olives are fabulous but watch out for making the focaccia OTT. It’s a fluffy bread and can take a lot of seasoning but you’ll know when you go too far, especially if you’re then going to be adding salt rich fillings like charcuterie, etc, to it later.

The maximisation of bubbles

So, it’s day three, you’ve made it all this way and you’ve moved your cold dough into the oiled tray. Can you bake it right away? Sorry…. But no.

If you baked your dough without dimpling, you’d get a lovely olive oil rich bread with a pretty regular crumb - nice, but not what we’re looking for. We want BUBBLES.

You’ll need to get the dough warmed back up to room temperature (about an hour) then leave it until it is totally bubbly and relaxed (another 30 mins - 1 hour, unless its warm!). Now and only now can you get your hands in there and do the famously enjoyable focaccia dimpling process. ASMR vibes for sure.

Although it might not look like it, there is actually a bit of a method to this. We aren’t actually trying to create divots in the bread - we are trying to redistribute the CO2 throughout the dough. So oil up your hands and use the pads of your fingers (not pointy!!!) to spread the dough out - as you press, bubbles of air will expand up into the dough and reveal themselves - it’s definitely a fun part of the process.

To really maximise things though, I like to dimple the bread and then… walk away. Leave it for 15-20 mins and then dimple it again just before it goes in the oven. I think you get the best bubbles this way!

Adding toppings

When you’re adding toppings, remember to really push them deep into the dough otherwise they’ll pop back out during baking and be more likely to burn.

At the bakery, we always used to keep our toppings pre sliced (onions) or pre-picked (rosemary) and in oil so they are ready to go into the oven and wouldn’t burn during the hot cooking process. It’s also worth thinking about whether your toppings would benefit from pre-cooking. I personally love to pre roast tomatoes - I think the final result is much better and you’re much more in control of all the juices and the final texture. I like it squishy!

Temperature

Although you may not feel like putting your oven on or making your own bread when it’s so warm outside, summer is the best time to do it! When your environment is warm, fermentation is at an all time high. Your yeast will thank you and you’ll be rewarded with the kind of bubbles that dreams are made of.

The deal with flour

It’s worth noting if you want to get max volume and outrageous bubbles, you need a flour that has enough protein (and the right kind of protein) to support the structure. At LBP, we used to use a very strong Shipton Mill flour called ‘ciabatta flour’ but at home I’ve always had good results with the Marriages Canadian or really, any supermarket own brand ‘strong white bread flour’. If you want to use a different flour then you should go ahead but expect a different result - whilst the process will still maximise flavour and gluten structure, your bread is always working within the limits of what it’s made of: The flour itself!

Ok, let’s do this!