Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

Today is a very exciting day as we welcome a new voice to Kitchen Projects - Bronwen Wyatt *screams*. You may know her as Bayou Saint Cake, with her iconic cakes and flavour combinations coming out of New Orleans. I’ll introduce her properly below, but I know she is the perfect person to teach us about cornbread.

On KP+, Bronwen has shared an alternative cornbread for your table - Smoky Poblano and Cheddar with fried sage butter. I KNOW. How lucky are we? Click here for the recipe.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc., the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £6 per month or £50 for the whole year. Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

P.S. I am still on tour in the US - my book SIFT came out this week and I’m currently writing to you from LA where I’ve been making pastries at Botanica with the brilliant Tessa Faulkner - we open at 9am + specials back on the brunch menu today. I’ll be at Now Serving tonight (November 17th) with Nicole Rucker before heading to the East Coast. My talk with Natasha Pickowicz on Tuesday 19th at Archestratus in Brooklyn is sold out, but there will be a signing line (info here) so we can still meet!!! AND for my midwest besties, I’ll be heading there next and will have details on my guest pastry and book signing at Diane’s Place soon!

Introducing: Bronwen Wyatt

While I’m sure plenty of you will already be familiar with Bronwen Wyatt and her work as Bayou Saint Cake, I’m thrilled to re-introduce her today.

Not to sound completely insane, but I’ve been lurking Bronwen’s instagram page for a long time. How many times did I shake my fist at my screen, furious that I couldn’t transport myself to New Orleans to get a slice of (or a whole cake, let's be honest) of Bayou Saint Cake? Too many to count.

Bronwen, simply, is a masterful pastry chef with *the coolest* style. If you haven’t already fallen in love with her sleek-yet-ruffly cake designs and gorgeous flavour pairings, you’re in for a treat.

Earlier this year, Bronwen decided to close her baking business and focus on writing and teaching on her specialist subject, with her own substack and running online classes. Though I’m sad I didn’t make it to Louisiana in time to get a slice of cake, I’m thrilled that she will be joining us here on Kitchen Projects in the coming months, ready to take on some of the most classic Americana bakes.

Today’s piece on Cornbread is a perfect introduction to her razor-sharp palate, enthusiasm for tradition (but never forgoing flavour for the sake of it!) and glorious curiosity. It’s a reflection Bronwen’s deep rooted love and knowledge of Southern ingredients. I learned so much reading this piece and…. I need to stop talking about how excited I am and just LET YOU READ THIS BRILLIANT WRITING.

Welcome Bronwen… over to you!

All About Cornbread

When I was growing up in Maryland, my Texan mother would always make cornbread in a cast iron skillet. It always featured yellow cornmeal, a crumbly texture, and crisp bottom crust. I’d eat my slices slathered in butter and honey. As I got older and started baking on my own, I favored sweeter cornbreads with tender, cakier crumbs - more reminiscent of Jiffy mix or the cornbread you’d get on the side at the rotisserie chicken restaurant Boston Market. This isn’t really surprising, considering my voracious sweet tooth, even though I knew, of course, that “real” southerners don’t put sugar in their cornbread. I don’t even remember learning this - it’s one of those things we absorb from the air in our humid summer childhoods.

But is that actually true?

I was so pleased when Nicola asked me for a deep dive into cornbread. It’s a dish I make all the time, often as a side for chili, the way I usually had it growing up. Here in the south, a cornbread’s texture can run the gamut from the hyper-traditional, featuring no wheat flour or sugar, to the fat yellow squares of sweet, tender cornbread you might find on the side at an all-you-can eat buffet. I’m firmly in the camp that both styles have their place in the canon, but I was eager to understand why we have such broad regional differences in such a simple dish.

Nearly everyone I spoke to for this piece, from the north and south alike, admitted to putting at least a little sugar in their cornbread. Others favored honey or molasses, or our more esoteric southern sweeteners, cane syrup or sorghum. Most everyone also used a combination of cornmeal and wheat flour - another deviation for cornbread purists. I commend folks who are passionate about preserving southern foodways, but the truth is a lot of the traditional cornbread I’ve had is a bit punishing - gritty and dense, and unpalatable without a hefty dose of butter. These unsweetened cornbreads are often eaten as a side dish, dipped into the jus running off a pile of braised greens (colloquially called pot likker), or crumbled into a bowl of milk for breakfast. Still, I was determined to understand the appeal of traditional, unsweetened cornbread made without wheat flour.

A History of Cornbread

Early colonizers in America found that corn, our continent’s only, precious native grain, fared better in the hot, wet climate of the American south than the more delicate European wheat. Long a staple food of the indigenous people of North and South America, it fast became a crucial part of the diet for European and enslaved African Americans. Early cornbreads were unleavened mixtures of cornmeal, salt, and water, sometimes enriched with pork fat. With the advent of the first commercially available leaveners in the 1860’s, southern cooks began to add baking soda to their cornbreads, activated with buttermilk. Like the cornmeal itself, buttermilk lasted longer in the heat and proved a more sensible pantry staple if you didn’t have refrigeration. When my great-grandmother Berta Lou, born in Collin, Texas in 1896, referred to “bread” or “milk”, she always meant cornbread and buttermilk - bread made from wheat was “light bread”, and regular milk was “sweet milk”.

Along with chemical leaveners, the late 19th century also introduced the first roller mills, which dramatically altered the texture of the cornmeal. Bakers started adding eggs to their cornbread, and as wheat flour and sugar became cheaper and more readily available, they made their way into many home recipes as well. In 1930, Jiffy produced the first commercial baking mix in the United States, and the ubiquitous blue box became for many the standard family cornbread. Two Louisiana chefs I talked to for this story both sheepishly admitted that they grew up on Jiffy, which does, indeed, contain sugar.

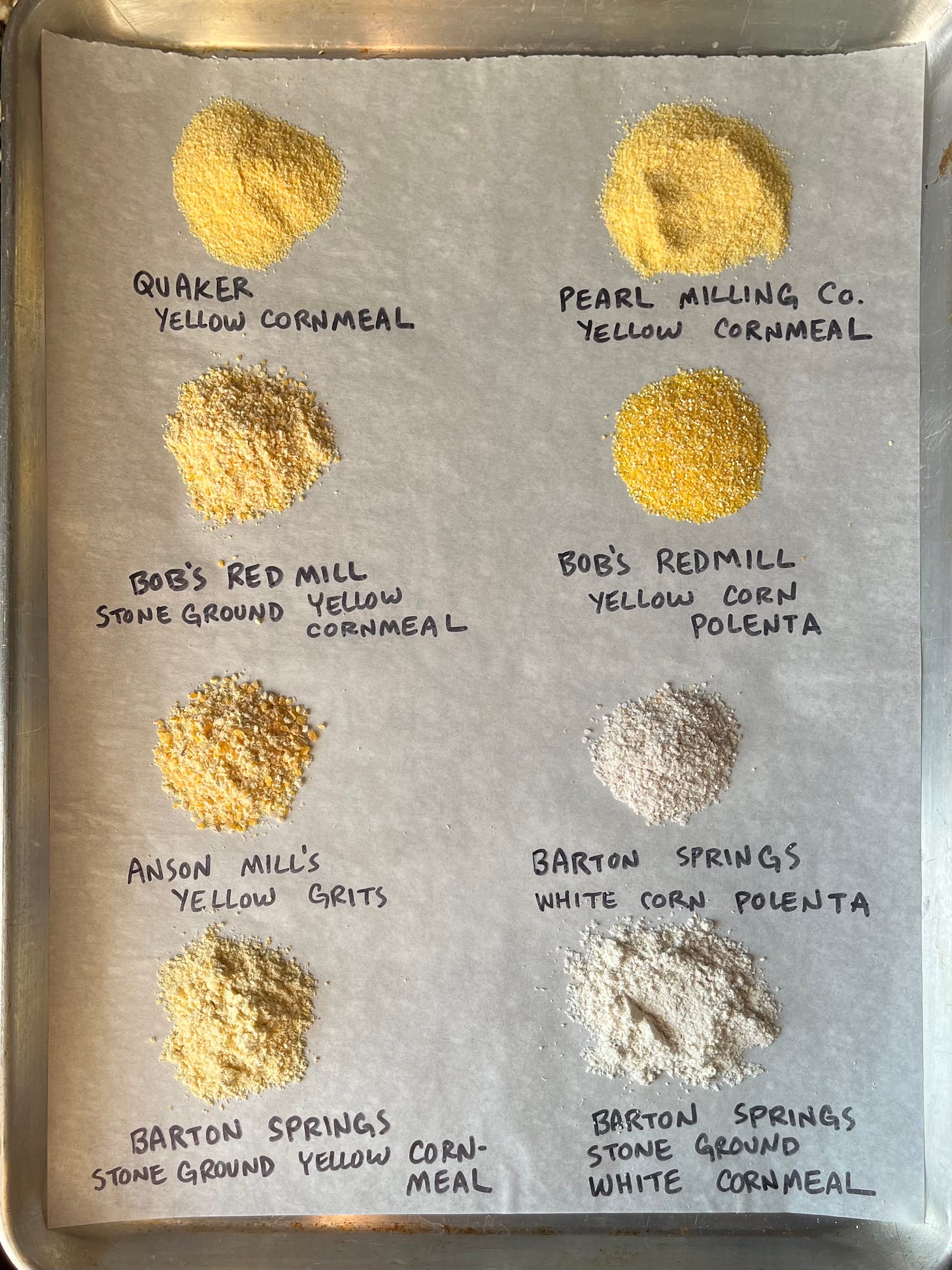

Comparing cornmeals

In his piece “The Real Reason Sugar Has No Place In Cornbread”, Robert Moss argues that the types of cornmeal we can commonly buy today are a far cry from the stone-milled grains of yore. In the United States, cornmeal is often characterized by its application. Here’s a brief overview of options from an American perspective:

The common names for ground corn’s various culinary uses, whether it be polenta, grits, or cornmeal, usually refer to the particle size of the grain (though there can be a tremendous amount of overlap among the different types).

Cornmeal is usually derived from one of two types of corn - flint or dent, the former rarely sold in stores in the US. Most of the cornmeal grown and milled in America is yellow dent corn, though some mills offer white cornmeal as well.

The majority of cornmeal found here is roller milled, resulting in a consistently coarse or fine grain size, depending on the product. Cornmeal meant to be cooked on the stovetop, like polenta or grits, is coarser than the type Americans bake with, which is sold here as “fine cornmeal”, “medium cornmeal”, “enriched, degerminated cornmeal”, or, confusingly, just “cornmeal”.

In Louisiana, you’ll rarely find bagged coarse cornmeal sold as “polenta” - it will almost always be called grits, which can come in either yellow or white varieties. Technically, polenta is supposed to be made from flint corn, and grits from dent corn, but many brands will label their coarse cornmeal interchangeably.

On the very finest end of the spectrum is corn flour, which in the south is generally used for battering and frying and is not the same as cornstarch (I’ve learned this is not true in the UK, where the names corn flour and cornstarch are used interchangeably). In the States, cornstarch is a pure white derivative of the starch in the corn kernel, while corn flour is the whole kernel, ground to the consistency of wheat flour.

NB. For the purposes of this recipe test, I’m leaving aside the topics of masa and hominy - I feel like I’m already going too deep in the weeds!

Stone Milled Cornmeal… is it worth it?

If roller mills produce a consistently-sized cornmeal grain, Moss argues that stone-ground cornmeal results in a diversity of particle size. I ordered several bags of stone-ground cornmeal from Barton Springs Mill in Texas to confirm, and it’s true - the cornmeal ranged from powdery to coarse within one bag. It’s this texture, says Moss, that produces a plush, tender cornbread without the addition of wheat flour. Further, large commercial roller mill operations harvest their corn crops early and dry them with forced air, while smaller stone milling operations may have the leisure to allow their corn to ripen fully in the field. And because stone milled cornmeal preserves the whole kernel of the corn, it has a more robust, sweeter, and corn-ier taste. The term “enriched, degerminated” cornmeal holds a clue - the oily germ and bran has been removed, making the product more shelf stable but depriving it of the full corn flavor.

Skeptical, I made a batch of traditional, unsweetened cornbread with stone ground white cornmeal, and reader, eaten straight from the oven while still warm it was a revelation. It rose tall, with an open crumb and true corn flavor. Far from gritty, this cornbread felt properly hydrated. I can understand how bakers, hungry to return to the memory of this cornbread, might add sugar and wheat flour to mimic the properties of the stone ground cornmeal. My recipe development goal was set: I wanted to develop a cornbread like this: barely sweet, deeply corny, with a moist interior and a crisp bottom, but that could be achievable even without access to beautiful heirloom stone milled cornmeal. It must also include buttermilk - the acidity deepening the flavor and making it more complex, a must in my opinion. Also, I want Berta Lou to approve.

The Elements

The inconsistency of the grain size in the stone ground cornmeal led me to think more deeply about the texture of the crumb of this cornbread. The finer the cornmeal grain, the more readily it will absorb liquid. But coarser cornmeal tends to be more flavorful. Glenn Roberts, the owner of the beloved Anson Mills in South Carolina, takes it a step further, arguing that the powdery element of the stone ground cornmeal allows it to properly interact with chemical leaveners, creating a higher lift and less dense crumb. This is why bakers might add flour to their cornbread when using roller milled cornmeal - to achieve a lighter product.

The cooking method might afford another clue to my ideal cornbread’s texture. Traditionally, fat, usually bacon grease or butter, is heated in a cast iron skillet which you pour the cornbread batter into. One recipe even notes that the batter should sizzle and bubble at the edge, producing a crisp bottom crust -but could it also give a head start to the hydration of the coarser grains in the cornmeal, tenderizing them? Last, could I push this even father by soaking the cornmeal in buttermilk before incorporating the rest of the ingredients? A bakery I worked at years ago adopted this method, soaking multiple batches of cornmeal in 12 quart cambros for the massive amounts of cornbread we’d bake off every morning.

The ratio of liquid to dry ingredients in cornbread recipes is remarkably similar across the sources I referenced (ranging from the 1950’s Junior League of Baton Rouge community cookbook to the Joy of Cooking, and more). Cornbreads featuring wheat flour had a roughly 50/50 ratio of liquid to dry ingredients, while all-cornmeal recipes featured 63-70% liquid. For my initial tests, I’d maintain the larger ratio of liquid, and play around with the types of cornmeal.

The tests

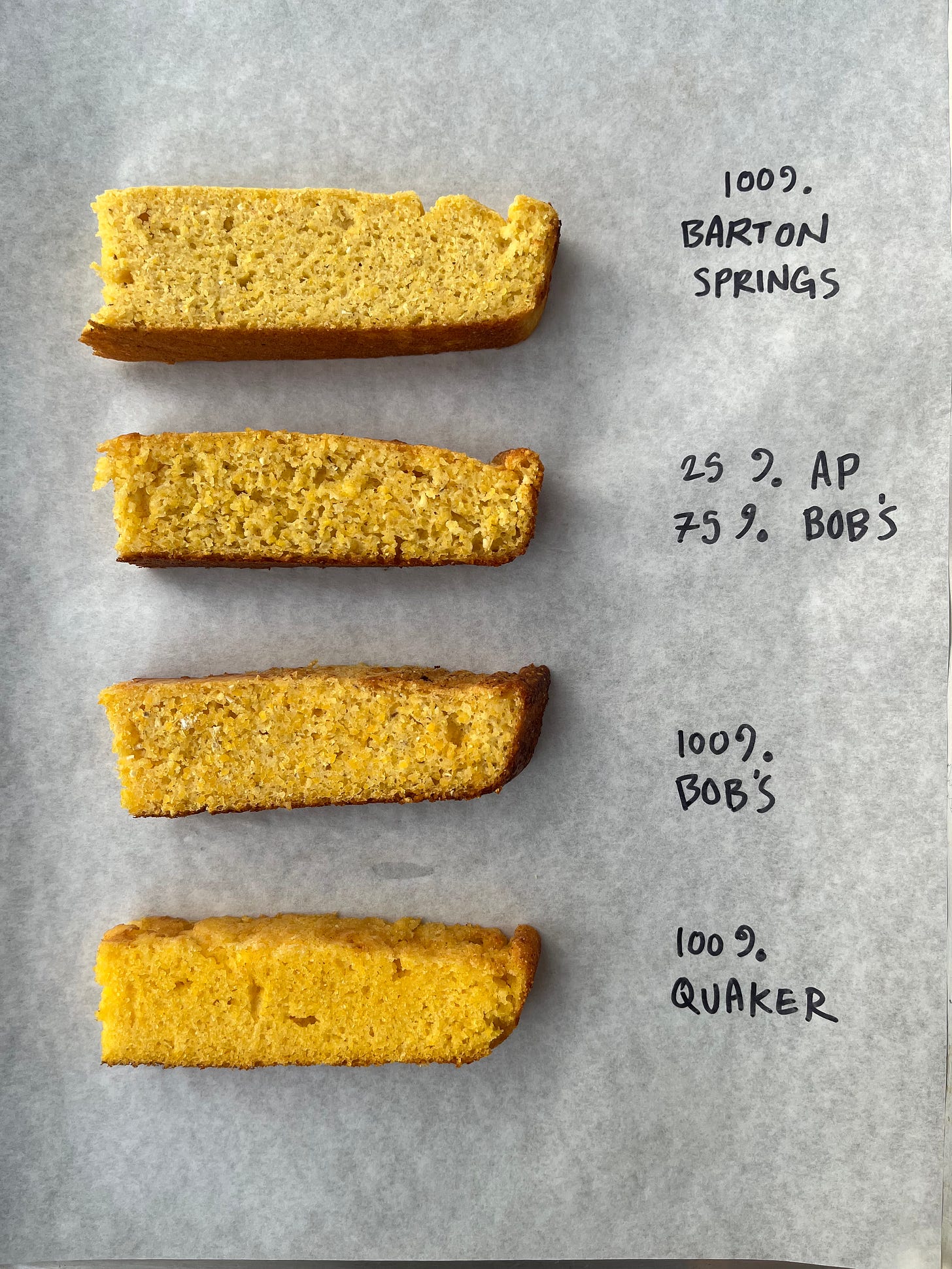

Test One: A purist’s cornbread

My first task was to confirm the theory that stone ground cornmeal resulted in a higher rise and sweeter taste. I made three batches of cornbread using an identical, traditional method and ratio - meaning no sugar, no wheat flour, and cooked in a hot cast iron skillet - and compared the texture. For my initial test, I used the gorgeous, premium Barton Spring’s stone ground yellow cornmeal, Bob’s Red Mill stone ground yellow cornmeal (the only stone ground product widely available in stores), and Quaker brand enriched, degerminated yellow cornmeal (by far the finest and most uniform of the bunch). The difference in both flavor and texture was remarkable. The cornbread made with the degerminated cornmeal was, frankly, horrible - like a sour, congealed baked polenta. Bob’s Red Mill produced a fluffier product, but the flavor I was seeking wasn’t quite there, and the pronounced buttermilk tang felt distracting. The heirloom stone ground cornmeal was the winner, but even then, after snacking on it over the course of a few hours, I started to feel like it wasn’t quite right. Fresh from the oven and slathered with butter, it was delicious, but as it cooled it lost a lot of its luster.

Later, I brought a sample platter of the day’s bakes to a dinner party and my suspicions were confirmed. The group of northerners and southerners alike agreed: they didn’t like the unsweetened cornbreads, preferring the boxed mix I provided for contrast over even the heirloom variety. A baker friend argued that the sugar-sweetened breads tasted more like corn. Only one pal, a former editor at Southern Living, liked the unsweetened version, telling me it reminded her of her Mississippi grandmother’s recipe. But was attempting a recipe married to tradition the right path if most people didn’t actually find it enjoyable?

Test two: Welcome back wheat and sugar

My recipe development goals now shifted - I wanted to find a version of a cornbread that was reminiscent of the old-fashioned type, but suited for a contemporary palate. Like many bakers before me, I turned to wheat flour and sugar to modernize my cornbread - the wheat flour to lighten the texture, and the sugar to boost the corn flavor. Most modern cornbread recipes feature a 50/50 ratio of cornmeal to wheat flour, and rarely indicate using one type of cornmeal over another.I’d start at 25% wheat flour, to preserve the more rustic texture of the traditional cornbread. I’d add enough sugar to tenderize the crumb, allow it to hold more moisture, deepen the corn flavor without overpowering it and help with browning. I’d sub out some of the buttermilk for sweet milk to mellow the tang and balance the flavors. I also eased back on the total amount of liquid and added a touch more leavener for a lighter crumb.

My next batch hit the mark, featuring an open, rustic crumb, balanced acidity, and deep corn flavor with just a hint of sweetness. Compared to the 100% cornmeal version, it had a lift close to the heirloom cornmeal despite being made with a mass-market brand, and a prettier golden-brown color. Even better, it maintained its moisture the next day, with a markedly superior texture than the unsweetened, flourless version. Convinced I was on the right track, the next step was to play with the fat and the baking method. I’d also try a batch with soaked cornmeal to see if I could push the corn flavor even further.

Test three: Fat, Pans and the deal with soaking

I made a batch using bacon fat instead of butter, tried out a round in a 9” cake pan without preheating it, and soaked the cornmeal in the buttermilk for the next trials. The bacon fat produced a gloriously crispy crust but the flavor in the cornbread itself felt overpowering - if you happen to have it around, it’s perfect for greasing the pan, but stick with butter for the batter. Soaking the cornmeal did produce a more-moist interior, but I found that I missed the crunch of having a few kernels of coarser cornmeal in the mix - part of the reason using the stone ground cornmeal produced such a superior cornbread in the first place.

Lastly, the cornbread baked without pre-heating the pan produced a much lighter bake and a taller crumb, but I missed the textural contrast. The juxtaposition between the tender interior and crunchy crust is one of my favorite things, and worth hauling out your cast iron pan for. As the cake-pan baked cornbread cooled, the crumb took on a dryer mouthfeel, giving some modest credence to the idea that pouring the batter into a very hot pan gives us a jump start on hydrating the cornmeal.

Last, I wanted to see if I could mimic the texture of the stone ground cornmeal with a product that might be more readily available in Europe. I found a bag of yellow coarse cornmeal labeled “polenta” at one boutique grocery store in New Orleans. I left about 30 grams of it alone, and ground the rest in batches in my spice grinder until it was a reasonable approximation of the stone ground cornmeal - a mix of fine powder and medium-sized particles. While not a perfect mimic of the stone-ground product, it made a delicious cornbread, if perhaps a tad grittier than previous batches.

After I finalized my recipe, I made one final batch, once again using the Barton Spring’s stone ground cornmeal. It’s still remarkable to me how much the consistency of the cornmeal affects the height of the cornbread - one again, the Barton Springs cornbread rose taller and fluffier. This time, with the addition of the wheat flour and the sugar, it held on to its moist, tender texture for far longer than the more traditional version.

Alright, let’s make it.

RECIPE: Cornbread

Ingredients

233 grams / 1 ¾ cups stone ground cornmeal (or home made, see description in previous paragraph)

77 grams / ½ cup + 2 tablespoons all purpose flour

20 grams / 1 tablespoon + 2 teaspoons sugar

1 ¼ teaspoon kosher salt (I used Diamond Crystal)

2 teaspoons baking powder

¼ teaspoon baking soda

2 eggs

255 grams / 1 cup + 2 tablespoons buttermilk, preferably full fat

160 grams / ⅔ cup whole milk

56 grams / 4 tablespoons butter, melted (for the batter)

30 grams / 2 tablespoons butter or bacon fat (for the pan)

30 grams / 2 tablespoons butter, melted (for brushing on top)

Plus: Flaky salt, for serving

Method

Preheat the oven to 450°F / 230°C conventional / 210°C fan

In a medium bowl, combine the cornmeal, flour, sugar, salt, baking powder and baking soda. In another bowl, combine the eggs, buttermilk, and milk.

Five minutes before you are ready to combine your wet ingredients with your dry ingredients, place a 9” cast iron skillet in the oven. My own cast iron skillet features steep sloping sides and is 2” in depth - if your own has slightly different proportions you may need to keep a close eye on the cooking time. One tester found that the cornbread cooked faster in their broader, shallower pan. This recipe will work best if your skillet is well seasoned - if your own skillet has some sticky spots, rub a little high-heat oil into the bottom before placing it in the oven.

After five minutes, add 30 grams of butter to the pan and return it to the oven.

Add the wet ingredients to the dry ingredients, mixing them together with a whisk until just barely combined. Drizzle in the 56 grams of melted butter and give the batter one more quick stir.

Carefully remove the preheated skillet from the oven and give it a swirl to evenly coat the bottom with the melted butter, which may be taking on the first hint of a nutty brown color at the edges. Scrape the cornbread batter into the pan and return it to the oven.

Bake for 23-25 minutes or until the cornbread is a light golden with some darker dapples of golden brown speckled across the top. Brush with the remaining melted butter and, if you like, sprinkle it with a little flaky salt.

Storage instructions:

Cornbread will keep well for up to three days at room temperature. I typically keep my own in my cast iron pan and top it with the accompanying lid to keep it fresh, though you could also tip it out of the pan and wrap it in beeswax cloth or plastic wrap. If you’re making yours ahead of time for a Thanksgiving stuffing, you can wrap it tightly and freeze it until you need it.

Really appreciate having metric and imperial measurements in the recipe. I weigh out dry ingredients in grams, but salt, leaveners and liquids I still tend to do imperial.

Loved this Bronwen! Absolutely delicious and I made it with a migraine and feeling like death so it’s also very achievable! Sam loved the article too! Lots of nodding and “ahh yess!” as he read it 🌽