Kitchen Project #131: Six Orange Cake

Bringing a cake from my dreams into reality and trip to a citrus farm

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

Today we’re toasting citrus season (which soon, we’ll be waving goodbye to!) with this ultimate Six Orange Cake, a juicy, bright and rich dream cake that I obsessed over for the best part of the year. I cannot WAIT for you to make this.

Over on KP+, the citrus theme continues with my recipe for spiced blood orange creme caramels. These are outrageously easy to make and have a divine, unctuous texture and rich flavour that is the perfect end to any meal. Click here for the recipe!

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc., the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £6 per month or just £50 per year (equivalent £4.10 per month). Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

PSST… I’ve written a book!

I can finally say that my debut book SIFT: The Elements of Great Baking out THIS YEAR!!! and it’s available to pre-order now. Across 350 pages, I'll guide you through the fundamentals of baking and pastry through in-depth reference sections and well over 100 tried & tested recipes with stunning photography and incredible design. SIFT is the book I wish I'd had when I first started baking and I can’t wait to show you more.

Dream a little dream of… orange cake?

Did you know that, on average, we blink about 15 times per minute? That equals about 15,000 times per day. A blink lasts between 100-150 milliseconds, meaning we spend about 41 minutes every single day with our eyes closed. Our brains are extraordinarily skilled at filling in missing information and striving forward on autopilot. It’s the phenomenon behind phantom limbs and the automatic filling-in of blind spots, where the brain compensates for a lack of visual information at near instant speed.

This might seem like a left-field start to a newsletter about baking, but I'm attempting to set the scene for the mental gymnastics that I have been going through for the last year. And it all begins with a photo of a cake.

In mid-2023, my friend, and fellow substacker,

travelled around Europe, researching and documenting recipes. During his brief stint in Valencia, he sat down at a local restaurant near his rented apartment and was served a slice of orange cake. He snapped a photo, enjoyed his cake (with much enthusiasm), and moved on with his life. A few weeks later, he was showing me through his travel photos when, suddenly, he stopped at the orange cake. My world turned upside down.After seeing this cake in July last year, I did not stop thinking about it. I haven’t developed such a deep and unwavering obsession with something I’d only seen on screen since discovering Buffy The Vampire Slayer at eight years old. And just like with Buffy, I was instantly and irreversibly bonded.

To me, it looked the perfect combination of juicy and velvety, finely crumbed with pure orange essence. I could taste it - imagining the soft syrupy base, the robustly wet centre, the tangy sweetness. It had enough move and groove in the crumb for the syrup to settle in, so it would be saturated throughout but with more structure than a tres leches. It had the richness of a cake, but the freshness of a just-cut orange slice. I knew everything about this cake from a single photo.

You see, the human brain is a playground of creativity: From the moment I saw this cake, it was like I had already tasted it. I was compensating and filling in gaps to the extreme - I could imagine how it felt in my mouth so realistically that it was like it had been me, not Jordon, who had eaten this cake. This cake was my blind spot.

I set a countdown - I was going to eat this cake. It was my destiny. But when? It made sense to save the trip for citrus season, when the oranges would be at their peak. After all, this wouldn’t be the first time I was trying it, but a revisiting of an old friend. I already knew exactly how it would look, what it would taste like. It wasn’t a first tasting, but a reunion! So, in early February 2024, I flew to Valencia and booked myself into the restaurant, ringing them to check they had the orange cake. “We just baked one today!” said the friendly voice at the end of the phone. Ticking off every second that got us closer to our orange cake destiny, we rushed through dinner to get to dessert. Finally, the time had come.

The trouble with pedestals is that they are actually quite fragile. I don’t know who coined the phrase, ‘you should never meet your heroes’, but they had a point. Creating an unfillable chasm of expectation for someone, something, or in this case, a cake, would always be a recipe for disappointment. It’s not that the cake wasn’t good - it WAS. There really was so much to love about it (The way it was sitting on syrup, meaning it had flavour throughout, was genius.) But it didn’t live up to the extraordinary heights I had assigned to it. And that wasn’t the cakes fault. It was mine.

However, the deep imprint of what my perfect orange cake could be was left in my mind. And I was not deterred - so, welcome to this very special, slightly deranged newsletter, where I try to recreate a cake from a memory that doesn’t actually exist. See why I started this newsletter about how weird our brains are?!

Today’s recipe

A symptom of our modern, social media’d minds, is that a great photo, or video is the currency that I, as an online food writer and recipe developer, have to trade in. I’m all too aware that a great dish might only be made if the photo is compelling enough; I promise I’ll always do my best to write recipes and take photos that write a cheque the flavour and taste will cash. So, after weeks of delving into the world of orange cakes, I’m thrilled to present my perfect ultra juicy, Six Orange Cake to you:

Over on KP+, the citrus party continues with my Blood Orange Creme Caramel recipe. A super satisfying and easy end to any meal, fortified with a blend of sugar and spices that is surprisingly complex for how simple it is to make:

Citrus heaven is a place on earth

A great orange cake needs to start with great citrus, so it’s no surprise that the heart of this recipe comes from Valencia. Despite being on the East coast of Spain, with orange tree-lined streets, 300 days of sunshine and perfect citrus growing conditions, Valencian bakeries and restaurants had a surprisingly small offering of orange desserts, cakes and bakes on offer.

I was also surprised to learn that the ‘famous’ Valencia Orange was first hybridized in California, USA, not Spain. The farmer responsible, William Wolfskill, named his new hybrid after Valencia, which was known for its prolific sweet citrus. It’s very possible, then, that these brand name ‘Valencian Oranges' are not available in Valencia at all, though a vast quantity of sweet orange varieties are. Thanks to the climate and geography, citrus thrives in Valencia. Harvested between October and early Spring, fruit grown in this region has an optimal flavour and has a ‘PGI’ (Protected Geographical Indication) designation to assure its origin and quality.

The history of orange growing in Valencia goes back to 1781, when the first commercial grove was planted. It makes sense, then, that the Todolí Citrus Foundation was established here in 2012. Founded by its namesake Vincent Todolí (a former director of the Tate Modern and Art Collector), the foundation is a botanical farm dedicated to the growing and preserving rare citrus. It may be the equivalent to the UK’s Brogdale Collections (which specialises in the growing of apples), except with heaps more sunshine.

The foundation preserves some 400 citrus varieties sprawling 40,000 square metres - from kumquats to bergamot, blood oranges to tangors, Citron to pomelos, it captures the rich history of citrus varieties. By looking beyond the commercially viable varieties, the foundation studies the development and biodiversity of citrus and tracks the evolution of the fruits, even discovering forgotten varieties. There is also a small museum and extensive test kitchen and research area on site.

I’ve wanted to visit the foundation since first hearing about it in 2022 and to finally visit was a dream come true. Due to my own administrative mix-up, I accidentally attended a tour that was entirely in Valencian. Fortunately, my friend and travel companion Claire could take notes and translate for us both. So, there we were, in the beautiful February sunshine (yes, really, it was glorious), we were guided through the groves, tasting our way through each category of citrus (citrons, pomelos, orange, lemon, lime) and marvelling at the vast varieties in the fruits.

Tracking the evolution of fruits is fascinating - these 400 varieties, which vary so extremely in size, texture and flavour, are derived from just three ‘mother’ fruits; Citrons, pomelos and mandarins. Citrus are good time fruits - up for mixing and matching in pretty much every single combination you can imagine; they are highly susceptible to mutation. (If you’d like to learn more about the history,

has written an excellent history of the Citron on her substack here) And as a result, the family tree, no pun intended, is diverse. From the entirely acidless citrus, to double crossed white fleshed pomelos, to blood citrus (where the juice is actually pigmented), to thin-skinned kumquats, to outrageously citric limquats, to the beautiful Buddhas Hand, to the antioxidant-packed shiikuwasha lime loved by Okinawans, the famously long-living community in Japan, I was overwhelmed by flavour. We were, sadly, too late for peak ‘caviar’ citrus, like finger limes, and Yuzu (my favourite!), so I’ll be back to try that in November and December of this year.I also learned a few excellent facts - did you know that all limes are technically yellow, but they are picked green?! And when you eat a kumquat, the sweetness and sugars fall to the base of the oblong fruit, so if you cut them up, you should always cut it vertically? And the first cologne (originating in Cologne, German) was made of citrus oils, primarily bergamot? And certain fruits have edible ‘albedo’ (more commonly known as pith), the white part of the citrus between the skin and the flesh, rich with pectin.

The Anatomy of Citrus

If this is the first time you’ve heard the word ‘albedo’, you’re not alone. It’s a new word to me, too. Eating the white pith, which is only faintly bitter and can be enjoyed thinly sliced (otherwise, it’s too tough), was a revelation. It reminded me that there’s a lot I have to learn about the best way to approach a citrus.

The very outer layer of the citrus is known as the ‘flavedo’. It comprises the colourful outer skin, aromatic oil glands, and a protective skin/cuticle. The ‘zest’ refers to the aromatic outer layer, whilst the ‘rind’ may include a little of the next layer, known as the ‘albedo’, the relatively flavourless (though possibly bitter) spongy white material that separates the fruit and flesh. The thickness of the albedo varies - citrons, for example, are majority albedo. The flavedo and albedo together make up the ‘peel’. Beneath the peel is the fruit flesh and pulp.

So where is the flavour ‘held’? A combination of zest oils and aromatic juice is usually the best way to represent the flavour of citrus. The best way to extract the oils is brute force - by grating, we are rupturing the oil glands. We can take this further by rubbing the zest with a mild abrasive, like sugar. You can concentrate the juices by heating and evaporating excess water, but I find this gives the citrus a stewed taste rather than a bright freshness that I crave.

The Family of Orange Cakes

The real question then, and the one I hope to answer, is how to translate that pure pleasure of fresh, juicy citrus into a baked cake. I pulled up the photo that had driven me so crazy with infatuation for the last few months and thought about how I could bring the orange cake from my dreams to our collective reality. I was aiming for a cake with a fine texture, a juicy top (and bottom)

I started by considering the iconic orange cakes that already exist - there’s a glorious landscape out there. From the impressive whole orange cakes (boiled AND fresh, we’ll get to that) to the syrup-soaked Greek orange cakes to the lemon drizzle adjacent loaves that swap in another citrus, I took inspiration from each of these and started my journey into orange cake land. Let me show you around:

Boiled Whole Orange Cake: I first encountered whole, boiled orange cakes at Ottolenghi. Extraordinarily simple, we boiled oranges until soft, blended with eggs, almonds and raising agents and baked. The result was a supremely rich and moist cake. I’ve since learned that this recipe is credited to Claudia Roden, first published in her 1968 cookbook ‘A Book of Middle Eastern Food’.

Whole Orange Cake: This cake, also known as ‘Sicilian Orange Cake’, takes a step out of the Claudia Roden recipe, forgoing the boiling and simply blending a whole orange (raw). This recipe is usually fortified with oil and flour, though it varies from recipe to recipe, compared to the boiled orange cake, which tends to stick to the same, four ingredient format.

Portokalopita: The traditional Greek orange cake is made with eggs, yoghurt, and lots of oranges with filo pastry. While I’m inspired by the final look of this cake (dense and juicy), I decided not to test any filo cakes this week as I believe these are their own category.x

Revani: Revani is a semolina-based cake popular in Greece that is soaked with syrup after baking. It’s not traditionally citrus, but the syrup is always aromatic and strongly flavoured - I was very inspired by the texture of this cake! ULTRA juicy. Thanks to

and Annie for teaching me about this cake!Orange drizzle/adjacent: The standard butter/sugar cake is fortified with zest and usually adorned with orange juice icing.

Cornbread - OK, this isn’t an orange cake. But looking at the cut-through texture of the original cake, I wondered if we could replace the liquid element of cornbread with orange juice for a citrussy cake. The low sugar would then be mitigated with a LOT of syrup. Maybe this could work??? Maybe???

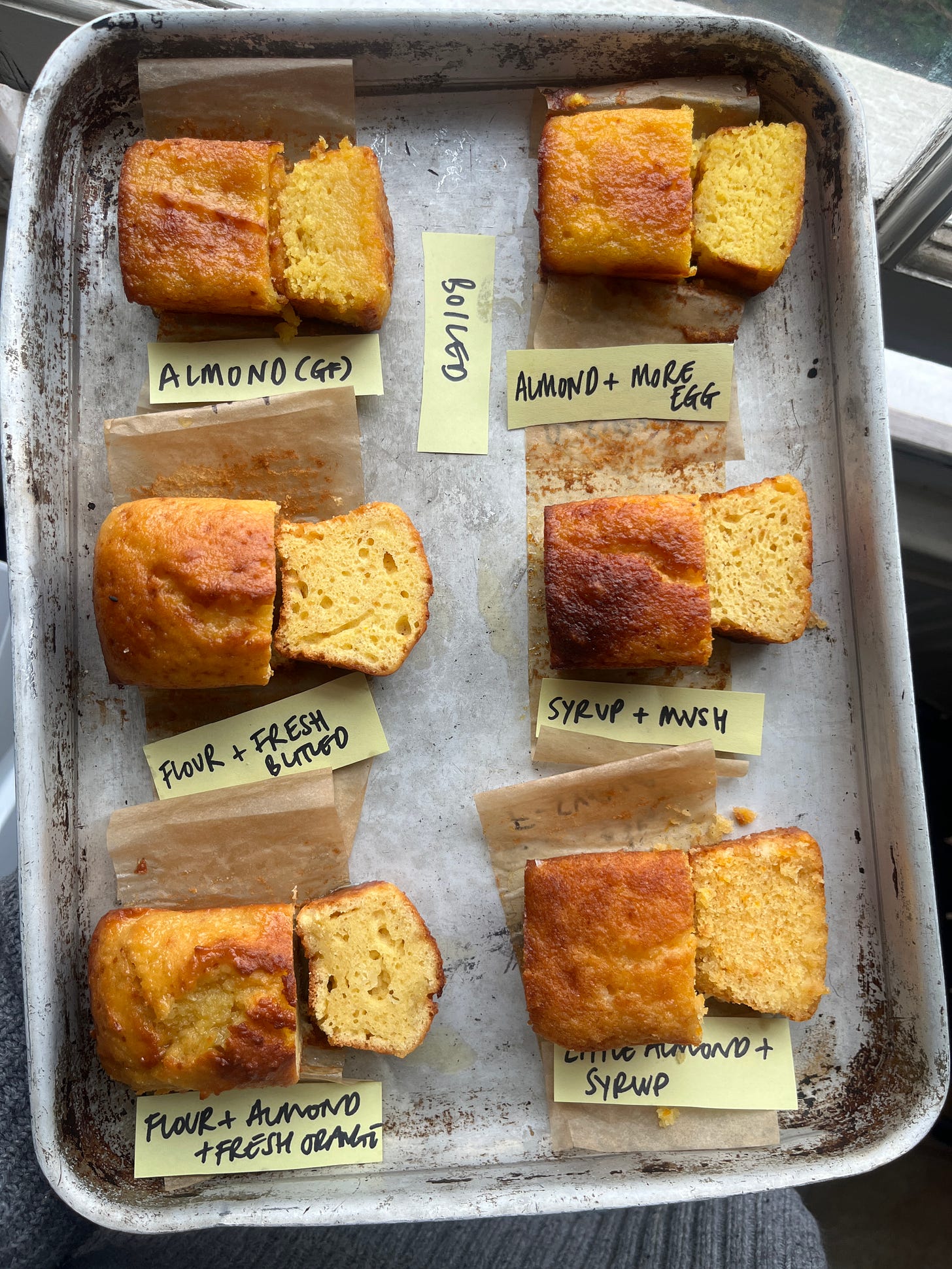

I mixed up a series of these cakes, with a few adjustments - I attempted replacing some of the sugars with an orange syrup, tested orange ‘mush’ (blended oranges leftover from juicing) as well as boiled whole and raw whole, as well as a variety of almond/flour combinations - to compare the flavour and texture.

The results

I wanted this cake to taste like biting into an orange, but cake. I know how stupid that sentence sounds now that I’ve written it out, but a goal is a goal. And though we got there in the end, there needs to be a content warning: Some of the cakes I made were real horror shows.

Though you might think blending a whole orange into a cake, boiled or otherwise, would lead to plenty of orange flavour, I’m afraid you are mistaken. The subtlety of these cakes, despite a gloriously moist texture, was a surprise. Comparing the boiled orange to fresh orange, the flavour was not too significant - the other ingredients, primarily the almonds, took centre stage. Though the flesh of an orange may taste impactful and flavourful, a lot is lost during baking.

There is an interesting point to be made here about the role of pectin in cakes - though you wouldn’t normally relate pectin to cakes, it does affect the crumb. Commercially produced cakes sometimes add pectin to help increase shelf life and improve moisture. It achieves this the same way it gels juices in fruit for jams, by binding with water.

Unfortunately, as we learned earlier, pectin is predominantly found in the albedo, which is flavourless. Meaning we need to weigh the benefits we get from the flavour with the benefits we get from texture. Why does everything always have to be a compromise?

The cakes made with syrup in the cake were delicate and moist, but again, the orange flavour was not as prominent as I’d hoped. The cornbread tests were interesting - instead of corn, I used a combination of flour and almonds (as much as I love polenta and corn flavours, that’s not what I was going for this week). The results were barely sweet breads, which, without syrup, were ‘not it’.

The best result was an almond enriched, but predominantly flour-based cake that used fresh blended orange flesh (no sigifnicant peel, but a little pith leftover from peeling) and a lot of zest. I went for butter, as the original had one. The result is a citrus-scented cake with plenty of structure, benefitting from a little pectin but focusing on the fresh orange flavour. The texture was great, but the flavour was not where I needed it to be. This leads me to…

The deal with syrup/types of syrup

This week I had to come to terms with the realities of cake making. For essential structure, a cake can only taste so much like something else - the crucial building blocks, the flour, eggs, sugar and fat, need to be prioritised. Certain rules need to be adhered to for a cake to be structurally sound. So although the idea of a cake tasting exactly like a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice, but having a pleasant crumb and texture, is slightly farfetched. The inherent flavours of our building blocks need to share the stage. This is where syrup comes in.

A syrup is an ideal vehicle for flavour. Not only can they be infused effectively, they can be added to a cake after baking to impart flavour after the essential structure is built.

To compare the viability of these cakes, and the role of syrup, I also made two versions and left one unsoaked. This allowed me to taste the orange level of the cake without the syrup, and taste the direct impact of the syrup. Unsurprisingly, the syruped cakes all had a superior flavour. But the quest didn’t end there.

The thing about syrup? It’s really, really sweet. And for it to permeate the cake properly, it needs to have the right viscosity. I tried soaking cakes with straight-up orange juice, and it turned the cake, rightly, to mush. Without altering the density of the liquid with sugar, the absorption is just all wrong. Think of sugar as a parachute, slowing down the movement of the liquid through the cake.

Syrup ratio

Looking at the lay of the land in syrup cakes, most cakes use a syrup that is equal parts sugar/liquid or more. And orange syrups sometimes use a combination of juice and water. I made several syrups to compare, and found that a 75% sugar syrup made with all juice, was, in my opinion, the perfect combination of fresh tasting and sweet, with a viscosity that doesn’t turn my cake to mush. To make the syrup zing, I use a combination of lemon and orange juice. The lemon helps the orange taste more like orange! And, as a final flourish, the method you’ll see below only heats up part of the juice to dissolve the sugar, mixing in the rest once it has cooled. This results in an optimally fresh-tasting syrup to maximise the flavour and avoid a too-cooked taste in the final cake. Zest is optional - it gives a slightly bitter marmalade-y flavour.

When to soak

The last thing we need to discuss is WHEN to soak your cake, and the relative temperatures of the syrup and cake itself. The potential combos here are as follows: Hot syrup + hot cake, hot syrup + cold cake, cold syrup + hot cake and finally, cold syrup and cold cake.

I found that hot syrup and hot cake was a disaster - the cake was so mushy and wrecked on top that it was difficult and unpleasant to eat. Though this might only be the case for my particular cake formulation, it was a no from me. I had the best and most controlled results from using cold syrup and cold cake (by cold, I mean maximum room temp) The structure of the cake was enhanced, not destroyed, and the level of absorption was at my perfect Goldilocks level. When you press the edge of the cake, you can HEAR the syrup - it is glorious.

One of the best parts of this cake is something I learned from the restaurant where this whole saga began - by sitting the cake ON the syrup, you get absorption from both the top and the bottom, without having to saturate the whole thing to the point of sogginess. (Side note: I asked the owner of the restaurant about the syrup at the bottom of the cake, and he said that it was baked on top of syrup - or there was an error in translation on my side - which, btw, DOES NOT have a happy ending. I tried a cake baked on top of the syrup, and although the base was divine, the amount of hot sugar that escaped and burnt on and around my oven was not something I can recommend)

The syrup makes more than you need to soak - you can dose individual slices by keeping a little to the side. The longer you keep the cake, the more it dries out at room temperature, so adding a little bit before serving looks beautiful and incredibly inviting.

The finishing touches

I tried a few variations for the final finish of the cake - from candied zest strips, to a marmalade/preserve jelly top. But for a zing of freshness, I don’t know that you can beat segmented oranges. To keep them looking fresh, I reduced the leftover syrup until it is spoonable (about 118c), which makes a perfect glaze. Though optional, serving with yoghurt is rather gorgeous.

Alright, let’s make it!

The recipe: Six Orange Cake

Serves 8

A note on oranges: Try to get the best quality, most fragrant oranges you can find for this recipe. Spanish if you can! I found it easier to locate better quality, but smaller oranges - of course, the AMOUNT of oranges in your cake will depend on the size. But for me, it was six or seven! About 1.5kg should be plenty. I used navel oranges.

Equipment: 1 x 8 inch cake tin

Cake ingredients

Zest of four oranges

185g Caster sugar

200g Butter, softened

1/4 tsp Flaky Salt

60g Ground Almonds

1-2 oranges peeled and blended to make 200g blended orange flesh (my oranges weighed around 200-225g per orange)

150g (about 3) Eggs

175g Plain flour

10g Baking powder

Syrup (this makes a bit more than you need,

3-4 x Oranges (my oranges weighed around 200-225g per orange)

1 x Lemon

225g Caster sugar

Pinch of salt

To serve

1 x orange, segmented

Thick greek yoghurt

The recipe

Preheat oven to 170c fan.

Wash the oranges briefly, then dry. Zest four of the oranges (about 20g) directly into the caster sugar. Use your fingers to rub the zest into the sugar to release the oils. Leave for 10 minutes for the sugar to fully draw out the oils; It will be very performed and turn a pleasant shade of orange.

Peel around 1.5 oranges and blend the flesh (you can leave some pith) - you need about 200g total. If you don’t have a blender, you can also just use 200g of freshly squeezed juice.

Whisk the eggs into the blended oranges and set aside. Sift the flour and baking powder together and set aside.

Cream the soft butter, almonds, salt, and zesty orange sugar together for 2 minutes until lightened. Scrape down the edge of the bowl, and then begin adding the orange/egg and flour/raising agents mixtures alternately in 3-4 additions. The mixture may look a bit split but don’t worry. We are trying to combine a lot of water and fat, so it will likely split - the cake will still be perfect.

Pour into a lined 8-inch tin and bake in the oven for 45-50 minutes until deeply coloured and a toothpick inserted into the centre comes out with just a few moist crumbs. There should be a deep, dark crust on the cake. You want this! Leave the cake to cool completely.

Whilst the cake is cooking, make the syrup. Juice the oranges - you want about 250g of juice. Juice the lemon - you need about 50g. Pour 200g of the juice mixture into a saucepan and add the sugar. Bring to the boil, then boil for 3 minutes. Take off the heat and leave to cool for a few minutes before whisking in the remaining fresh juice and a pinch of salt. Leave it to cool completely, and then taste - it should taste fresh and sweet! If desired, you can add more citrus zest here. It will have a more marmalade-y flavour if you add zest.

Once both the cake and syrup are cool, pour around 100g of syrup on top of the cake, allowing it to flow down the edges, too. Leave for 1 minute, then pour another 50g syrup on top. Leave for 5 minutes.

Pour 125g syrup on the plate you will serve the cake from. Carefully de-mould the cake (sorry, this is a bit sticky!) and use a spatula to help move the cake onto the syrup-laden plate. Lift the cake to let the syrup flow underneath for max absorption. Leave to soak for about 20 minutes at least before serving.

Keep about 50-75g of syrup to one side to additionally dose the cake when serving. You can also use it to ‘feed’ the cake as it dries in the coming days.

To finish, boil the remaining syrup until it reaches 118c or is very thick and syrupy. This will be the final glaze. Segment an orange, cutting each piece in half lengthways to make a beautiful thin segment. Lay on top of a pattern and brush with the thick glaze for extra shine.

Keep at room temp (will last longer without the segments!) for 1-2 days. To serve, spoon a little syrup onto the plate and place a slice on top. Top with more syrup, if desired. If desired, enjoy with yoghurt.

Sitting the cake on the syrup it so smart!!!

Hi Nicola, could the almonds be substituted for something else eg more flour (for nut allergy people)?