Kitchen Project #127: Plant-based Meringues 🌱

It is VEGANuary afterall. A new Baking Remix column by Brian Levy!

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

I’m utterly thrilled to introduce you to the latest edition of Brian Levy’s Baking Remix on today’s newsletter. This time, Brian is investigating the world of meringue through a plant-based lens. It is vegan-uary, after all.

For KP+, Brian has brilliantly married together his plant-based meringue recipe with his plant-based whipped cream recipe from December to create the most gorgeous mont-blanc, perfect trio of creamy, crunchy and.. chestnutty. Click here for the recipe.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc., the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month or £50 for the whole year. Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

PSST… I’ve written a book!

I can finally say that my debut book SIFT: The Elements of Great Baking out THIS YEAR!!! and it’s available to pre-order now. Across 350 pages, I'll guide you through the fundamentals of baking and pastry through in-depth reference sections and well over 100 tried & tested recipes with stunning photography and incredible design. SIFT is the book I wish I'd had when I first started baking and I can’t wait to show you more.

Marvellous Meringue… no eggs required

by Brian Levy

In today’s edition of Baking Remix, we’ll take a close look at meringue. Its sugary clouds were egg-white-dependent until very recently; chickpea cooking liquid, later coined aquafaba, was discovered as an alternative less than ten years ago (more on that below)! That means there’s still plenty of exploring to do with legume-powered foams. It’s the new year–a season, however fleeting, during which many people veer towards plant-based and generally lighter foods–and there’s no better time to dig into these featherlight confections.

About the Egg

The “Incredible Edible Egg” marketing campaign pushed by the American Egg Board beginning in 1976 does not, in my opinion, oversell its subject. Eggs truly present a dazzling array of potential uses. Consider the multiple options for simply boiling a whole egg (Soft-boiled? Hard?), not to mention the poached egg, the omelet, the scramble, etc., etc. Then there’s mayonnaise, citrus curd, custard—to all of which egg yolks lend their emulsifying and thickening powers. There’s sabayon, meringue, nougat, and macarons, which depend on egg foams for their lightness and texture, be it chewy, crispy, or frothy. (And those are just some of the egg’s edible applications; I’ve also used egg yolks for the millennia-old inedible application of tempera painting.)

Egg Whites

Let’s separate the egg here and focus on the white, leaving the yolk for a future post. The white comprises about two-thirds of the average “large” egg’s contents; that’s 33 grams for a 50-gram egg. The white itself, according to Harold McGee in On Food and Cooking, is made of 90% water and 10% protein, “with only traces of minerals, fatty material, vitamins...and glucose.” The white exists to offer cushioning (think waterbed) between the shell and the embryo, along with a quarter of the egg’s total nutrients. In addition to their nutritive value, the white’s particular proteins provide “a chemical shield against infection and predation…” And for our culinary purposes, this amalgam of proteins and water positively foams with potential.

Egg Whites + Sugar = Meringue!

Meringue is perhaps the purest culinary manifestation of the egg white’s power to develop and maintain a foam structure. As usual, for the scientific explanation of how meringue works, I’ll paraphrase McGee here. When we whisk egg whites, we agitate the proteins they contain in such a way that they “unfold and bond to each other.” At the same time, air is being incorporated into the mix, and the rearranged proteins suspended in the egg whites’ water hold both the air bubbles and their liquid bubble walls in place. Stable as an egg white foam may appear, it would eventually break down if not for the addition of heat and sugar. Heat activates the ovalbumin protein that “more than doubles the amount of solid protein reinforcement in the bubble walls.” And sugar gives meringue stability, gloss, body, and (once baked) crispness. Baking also means the water in the bubble walls evaporates and leaves behind a solid foam structure. There are no less than eight types of protein in an egg white, each with a unique function, both natural and culinary, so it’s little wonder that uncovering a substitute in the plant kingdom has been a challenge.

The origins of meringue--both the word and the recipe--are a bit sketchy. According to Patrimoine Culinaire Suisse, the first confirmed use of the word in French dates to 1691, but a detailed narrative may be gone for good; the Museum of Culinary Art of Frankfurt claims to have possessed a number of meringue-related documents that were destroyed during the Second World War. In any case, meringues are typically classified as either French, Swiss, or Italian.

French meringues are the simplest: one part egg whites to two parts sugar, whipped to a glossy white mousse and baked dry to crispy, voluminous clouds.

Swiss meringue uses the same ingredients, but they’re combined (and, traditionally, whipped) over a bain-marie, which dissolves the sugar and, once baked, yields a firmer, less crumbly meringue relative to the French. It can also be put to use in recipes such as that for buttercream.

Finally, for Italian meringue, sugar is added to egg whites in the form of a boiling syrup at around 120°C / 245°F, producing a silky, stable mousse that requires no baking and can be used for all manner of confectionary ornamentation. Because of its stability, Italian meringue is preferred by professional patissiers for use in the batter of macaron shells. In French, the noun meringue refers specifically to the baked confection. In their unbaked state, egg whites beaten with or without sugar are described as montés en neige (literally, whipped to snow).

Whatever we call it, egg white foam figures into countless desserts and confections (not to mention cocktails), and cracking the door open to plant-based alternatives via meringues means also inviting in plant-based flourless chocolate cakes, macarons, meringue-topped pies, baked Alaskas, and more. As always with finding alternatives to animal-based ingredients, it’s just a matter of cracking that initial code that allows for limitless possibilities.

Tricks of the Trade

It is possible to overbeat egg whites to the point where the foam destabilizes and curdles. Over the centuries, techniques have been developed to help avoid this end: using a copper bowl, adding acid in the form of lemon juice or cream of tartar. These issues are related to the specific protein bonds of egg whites and do not apply to the plant-based substitutes we will attempt below.

Allowing egg whites to age (i.e., allowing some of their water content to evaporate, therefore slightly concentrating their proteins) or adding meringue powder are techniques for ensuring a strong, stable foam structure. I don’t find either necessary, as I have always found meringues made with egg whites to be reliably strong. Although I did not try it, I imagine that concentrating other foam-encouraging elements such as the starches and proteins in chickpea aquafaba would offer extra strength to the resultant meringues. But, again, I have not found such a precaution necessary.

The tests: Plant-Powered Meringue

With all this talk of eggs, it’d be no surprise if you’ve forgotten that my goal here is to not use them—and to still end up with billows of French meringue. The point of the egg talk is: whatever alternative we use has a lot to live up to.

THE CONTENDERS

Aquafaba (from canned chickpeas).

The discovery that the liquid from a can of chickpeas could take the place of egg whites to make certain foams was made in France, according to The Washington Post, by an opera singer and vegan food blogger named Joël Roessel. (You can see the page where he logged his experiments here.) That was in December 2014. Roessel’s discovery caught on, and in the months that followed, the term aquafaba was coined (from the Latin aqua, or water, and faba, or bean) and subject-specific Facebook groups popped up, including Aquafaba (Vegan Meringue – Hits and Misses!), which would eventually have over one hundred thousand members. By May 2016, both The Washington Post and The New York Times had published stories about this exciting new ingredient.

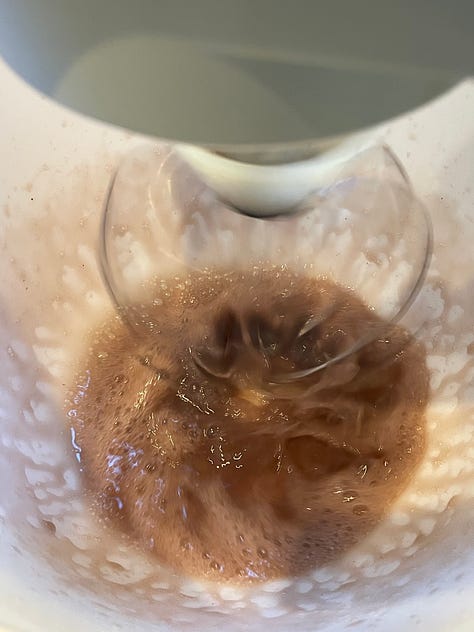

But how does aquafaba work? For once—gasp—no such subject could be found in the 2004 2nd edition of On Food and Cooking. Searching for answers in March 2016, the administrators of aquafaba.com published the results of a lab-performed nutritional analysis of the liquid (95.4% water, 1.6% starch, 1.3% sugars, 1% protein). And McGee chimed in for both the Post and the Times pieces with his theory: “the key” to aquafaba’s performance, he told reporter Jane Black, “is its viscous mixture of protein and dissolved starch, which slows down the collapse of a foam, as well as chemicals called saponins,” which are “known for their ability to stabilize bubbles…” In my unscientific imagination, there’s some unique alchemy that occurs with the combination of boiling water, the starches and proteins of the inner chickpea, and the seed’s almost slimy, collagen- or seaweed-like translucent skin. (And if you’ve ever boiled a chickpea-flour pasta, you know how difficult it is to contain its expansive foam.) There’s no other bean that has that same skin–others are thinner or thicker, tougher or more brittle–and my intuition, for whatever it’s worth, tells me this skin is the key to chickpea water’s stable foaming potential.

A Pea Protein Powder Formula.

I always keep unflavored pea protein powder around for plant-based experimentation, mostly for instances in which I would otherwise use milk powder. It has a fairly neutral flavor and dissolves pretty well. Given it’s sourced from a fellow legume and that an egg white’s foaming ability comes from its proteins, I confidently hypothesized that pea protein powder mixed with water would be an easy alternative to aquafaba that wouldn’t require finding a use for canned chickpeas.

Chickpea Aquafaba + Pea Protein.

I also considered that if my pea protein experiment were not successful, perhaps fortifying canned chickpea aquafaba with a dash of protein powder would give meringues a more stable structure and a glossier finish (Given that aquafaba lacks the relatively high protein content of egg whites, I thought that protein might be the key to meringues made with the latter’s pearly finish).

Canning or Cooking Liquid from Other Varieties of Beans.

Echoes of the suggestion that water from beans other than chickpeas works as aquafaba, too, reverberate throughout the internet, but far more scarce are accounts of persons who’ve actually put other bean waters to the test. To try for myself, I pulled my dried Christmas lima beans from the pantry and bought all varieties of canned beans I could find in the local grocery store: butter (a.k.a. lima), red kidney, and black.

A Chickpea Flour Formula.

Like pea protein powder, chickpea flour is an ingredient I always have in stock, mostly for making the Mediterranean pancakes called socca or farinata. (Note: chickpea flour is not necessarily the same as gram flour, as the latter can be made with some proportion of chana dal rather than chickpeas.) Considering we know aquafaba from chickpeas works as a substitute for egg whites, it didn’t seem a stretch to imagine that chickpea flour mixed with water would have similar if not identical properties. And at least one person on the internet claims it works!

TESTS AND RESULTS

The Control: Meringue française

To test my potential egg white alternatives, I employed each in the simplest of meringue recipes: the French meringue, which is traditionally made with equal parts (by weight) of egg white, caster (granulated) sugar, and icing (powdered) sugar. The egg whites are whipped to a foam, the caster sugar is added as they continue to gain volume, and, finally, the icing sugar, which is fine enough to quickly dissolve and contains 3% cornstarch to help reinforce the meringue’s structural stability, is folded in.

Aquafaba (from canned chickpeas).

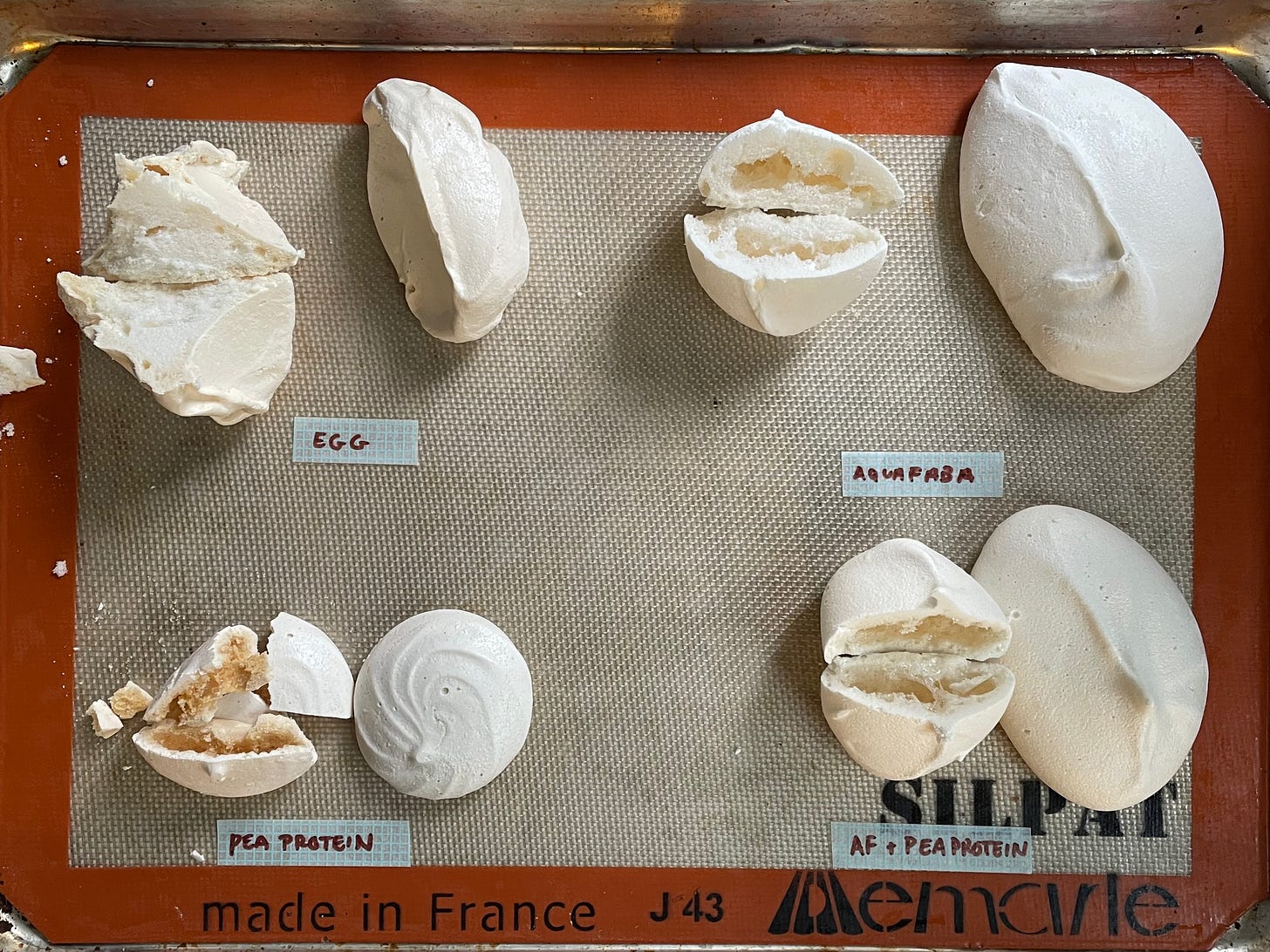

No surprises here; aquafaba meringue whipped up in a matter of minutes and was easy to pipe and spoon. Baking produced meringues that were very similar to those made with egg whites, with these subtle differences: the finish of the aquafaba meringue’s shell is flatter, less pearly, and the mouthfeel is slightly less satisfying in that it doesn’t have a certain tongue-coating creaminess that egg whites offer. Another difference: aquafaba meringues spread slightly more than their egg white counterparts, losing some definition in their height and gaining circumference. Editors note: Plant-based meringues tend to be more hollow, in my experience.

A Pea Protein Powder Formula.

I attempted to mimic the protein-to-water ratio of egg whites by combining 14 grams of pea protein powder with 86 grams of water. With multiple tests, I variously combined them at room temperature; I boiled them together; I added boiling water to the powder. No combination proved perfect, but my best results came from adding boiling water to protein powder. After whipping with sugar for a long time, 10 to 15 minutes, a solid enough foam had formed to shape mounds and bake. But the result was disappointing: brown and hollow inside, with a grainy texture and unpleasant vegetal flavor.

Chickpea Aquafaba + Pea Protein.

I thought protein might be the missing link to keep aquafaba meringues as structurally sound and glossy as their egg white analogues, so, although I didn’t like the ingredient on its own, I hoped that the pea powder protein would supplement aquafaba where it fell short. While adding a dash of protein powder did result in meringues with a subtle shimmer, it unfortunately added an unpleasant grit to the texture.

Canning or Cooking Liquid from Other Varieties of Beans

I had no success with my attempts to make meringues using the water of canned beans other than chickpeas. My attempts with butterbeans, red kidney beans, and black beans all produced enough foam to get my hopes up but all eventually let me down when they failed to get beyond a weak froth or collapsed with the addition of sugar. Of the three, black bean water got the furthest along. But sooner or later, all (literally) went down the drain. My two-birds-with-one-stone attempt (not chickpeas and not canned) was with dried Christmas lima beans. After soaking them, I cooked them with a minimal amount of water. I cooled and strained the liquid then tried to bring it to life in the mixer, where it got frothy enough to become opaque but made no progress beyond that.

A Chickpea Flour Formula.

I tested chickpea flour as I had pea protein powder: I mixed it with room temperature water, boiled water, and I boiled it together with water. I whipped the resultant liquids whole, I whipped them strained. Nothing went beyond the frothy opaque liquid stage.

CONCLUSION

I’m always hoping to figure out something new, to prove that the obvious and established solution isn’t necessarily the best one… But in this case, it was.

The best vegan alternative to egg whites for meringue is canned aquafaba, the liquid strained from a can of chickpeas. I had big dream for other egg-white alternatives and had hoped that some other formulation would do the trick and thus eliminate the need to open a can and find a use for its solid contents. But alas, nothing I tried came close.

My personal mission aside, the good news remains that aquafaba is a highly effective if still rather mysterious substitute for egg whites in foam-based sweets like French meringues. The only notable differences I observed between aquafaba meringues and egg white meringues are minor visual, flavor, and mouthfeel differences. Egg whites offer a more pleasing, perfectly smooth and glossy finish, and they retain their shape more perfectly while baking; aquafaba meringues have a barely tangy aftertaste, which becomes fairly imperceptible once they’re combined with other elements; and egg white meringues have an edge over aquafaba meringues in terms of mouthfeel, in that the former has a silky smoothness on the tongue as it melts.

Once I’d concluded through my French meringue tests that chickpea aquafaba was the best substitute for egg whites, I tested Swiss and Italian meringues using aquafaba. Both were successful. And, in fact, working with aquafaba adds an unexpected shortcut to Italian meringue: because aquafaba doesn’t congeal when heated as egg whites do, it can be combined with sugar and boiled directly in a saucepan, and then the mixture can be whipped–no separate sugar syrup necessary!

On to the recipe…

PLANT-BASED FRENCH MERINGUE

Makes 12-15 6-cm / 2 ½-inch meringues

Ingredients:

70g (5 tablespoons) aquafaba (liquid from a can of chickpeas, strained through a fine-mesh sieve)

½ tsp vanilla extract

70g caster sugar (a.k.a. granulated sugar)

70g icing sugar (a.k.a. powdered sugar)

Method

Prepare a pastry bag with a round tip (preferably a 1.3-cm / ½-inch tip or similar). Line a half sheet pan with parchment or a Silpat. With a rack positioned in the middle of the oven, heat the oven to 95°C / 200°.

Using a stand mixer with its whisk attachment affixed, whip the aquafaba and vanilla on medium-high speed until it is fluffy-foamy, with no remaining visible liquid, about 2 minutes. With the mixer running on medium speed, gradually sprinkle in the caster sugar over the course of a minute or two. Continue to beat on medium-high speed until stiff peaks form, 5 to 10 minutes. Remove the bowl from the mixer and remove the whisk attachment from the bowl. Sift the icing sugar over the meringue, and gently fold it in using a flexible spatula.

Transfer the meringue to the pastry bag and pipe 6-cm / 2.5-inch mounds, about 3.5 cm / 1.5 inches high, onto the lined sheet pan. Bake for 2 ½ hours, until they feel very dry and light. Let cool completely in a dry spot (humidity is the enemy of baked meringues!) before proceeding to the next step or storing in an airtight container.

The oven is likely the driest spot in your kitchen, so if humidity is a problem for you, turn the oven off after 2 hours and let the meringues cool along with the oven. You can leave them in there for as long as overnight, but doing so will eliminate the pleasant interior chewiness produced by a shorter bake.

Kept in an airtight container in a dry, cool environment, these meringues will last up to 5 days or more (the drier and crispier they are initially, the longer they will keep).

NOTE: To make this recipe the traditional way, simply replace the aquafaba with 2 egg whites (about 70 grams).

To turn this vegan meringue into a plant-based pastry masterpiece, check out KP+ now for Brian’s recipe for Mont-Blanc, the chestnut and cream confection of dreams:

This was a fascinating read. Thank you for sharing! Has anyone tried making meringues without sugar? Will the meringue collapse in the oven or will it hold its shape, just taste terrible? I make fancy cakes for dogs and want to make some sugar-free meringues (egg whites are totally fine) for decoration

This was fascinating from beginning to end! My mother made some wonderful meringues (she often added chocolate chips to hers!). As an avid chickpea lover, I’d like to try the aquafaba recipe you share and taste test it against the egg white version. Would it work equally well with aquafaba made from dried beans?