Kitchen Project #117: How to Pair a Pear

What actually IS flavour, anyway? + London pop-up next weekend!

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. It’s so lovely to have you here.

This week we’re diving into a big question: What is flavour? Is there a reason certain combinations are classics?! And what makes a great pair? What about pears?!

Over on KP+, I’m sharing a recipe for a really, really good biscuit: Sticky pear and ginger shortbread. You can add hazelnuts and chocolate, two kindred pear spirits, but it’s a flexible little cookie you’re going to LOVE (and it doesn’t spread). Click here to make it.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc., the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

Pop-up announcement: Pies & Soft Serve next Sunday, 15th October.

I'm THRILLED to be coming out of my Lark! pop-up hibernation with a very glorious event in East London next Sunday, 15th October: Pies & Soft Serve!

I love nothing more than collaborating with people I love and respect in the industry, and I’m excited to be working (again) with my unbelievably brilliant friend and mentor Verena Lochmuller, head of pastry development at Ottolenghi Test Kitchen, along with the genius ice cream makers Soft & Swirly!

We'll be open from 12 midday, celebrating autumn and serving seasonal fruit pies with soft serve, toppings and hot custard. I can't wait to announce the menu (going into testing overdrive from today), but expect an orchard full of joy wrapped up in the flakiest, butteriest pastry. We have limited numbers, so it'll be first come, first serve, and once we run out… we're out!

Find us at Soft & Swirly at Netil Market, 13-23 Westgate St, London E8 3RL. We'll open right at 12 when the market opens. We're right by London Fields / Broadway Market. There are so many fantastic traders down there, you'll be able to have such a feast. I share all the updates on my pop-up bakery insta handle @bakerylark so check there for all the info!

Finding flavour

When developing recipes, I often feel like my role (before being a chef) is to be a professional matchmaker. From pairing up complementary textures to introducing flavours and letting them co-mingle, I'm always looking to build a team greater than the sum of its parts.

But how exactly do these matches come together? Where do they come from? Is there a rhyme or reason that we encourage two ingredients together? Is it memory? Perhaps it's historical? Or maybe it's just because they seem like familiar bedfellows?

It's an intriguing topic. Certain couples go down in the hall of fame: Strawberries and cream, ginger and soy, apple and cinnamon, cheese and onion, peanut butter and jam, tomato and basil, honey and mustard. But what is it about these pairs that make them so successful? Is it their similarities or their differences? Surely there's a formula that explains it all to us?! There are certainly examples I've cited and come across in the past, like the way blueberry and coriander seeds contain linalool, a double-down effort resulting in an emboldened flavour. But is that just the beginning? Are there other soul mates that I should be matching all the time?

In the same way that I love knowing that an egg white will always whisk up into a glorious foam, this week, I wanted to understand if there was any certainty between flavours or aromas, any undeniably irresistible, intertwined destinies between certain ingredients. What makes a classic... a classic? With one of my favourite autumnal prizes, the pear, as my subject, I spent the week thinking about how to pair a pear. Shall we get into it?

Flavour vs. Taste

To start, we should break down the way we perceive food and the language around it. Though they might seem interchangeable, taste and flavour refer to separate things entirely. (Shout out to Claire Dinhut, a bonafide condiment expert, who first explained this to me!). Taste refers to the five basic tastes - Sweet, salty, bitter, umami, sour - while flavour refers to the entire eating experience, adding aroma (scent), the chemical reactions (heat) and all other sensations we experience into the mix.

It's estimated that >80% of our flavour experience comes from aroma and less than 20% from taste. Losing your sense of smell - as so many of us did during the pandemic - leaves food bland and lifeless, the joy completely removed. There’s also the importance of texture - whether something is crunchy, soft or chewy impacts our experience.

When we eat, we get two hits of aroma: Firstly 'orthonasally', when we get a whiff of something delicious externally, and secondly 'retronasally', when we experience aroma as we eat. Odours and aromas are potent triggers for memory and emotion because the olfactory system (olfactory is the medical term for anything relating to our sense of smell) has a unique structure.

Unlike our other senses, which take different routes to our brain, aromas are sent via the limbic system. This area of the brain is typically associated with memory and emotions, meaning scent has incredible power to influence our mood and emotional reactions. Every time we take in a scent, we file it away in a personal library - it's why I can't walk past a pre-heating deck oven, the previous day's flour burning off, without being transported to a bakery under a railway arch in Bermondsey, circa 2016.

Aromas (and noses) are not created equal…

Aromas, at their essence, are groups of volatile organic compounds transmitted by ingredients, materials, and people (!) that find their way to you and your olfactory system. These can be categorised by the particular notes of each scent (which we'll go into next) or may be referred to by their lasting power. For fragrances, these are known as 'head' (top notes lasting just 5-30 mins) to heart (middle notes which appear around 30 min) and base (bottom notes which appear after an hour or so). Head notes are the 'first impression' of a scent and tend to be vibrant fresh scents like citrus and herbs, while middle notes may be more floral or green and base notes tend to be more woody. These compounds appear to us at different stages because of their molecular weight - the heavier the compound, the longer it takes to evaporate and make its way to our nose.

Thousands of volatile compounds make up aromas, but scientists have identified many key players in our food and drink. From aldehydes, a variety of which appear in vanilla, cinnamon, almonds, oranges, olive oil and apples, to esters, which appear in force in fruity scents like pear, banana or pineapple, to terpenes, which represent piney notes in citrus and spices, there's a chemical compound responsible for your favourite (and least favourite) smells.

There's a hypothesis floating around the molecular gastronomy community: Ingredients that share aromas and molecular compounds are sympatico, guaranteed besties.

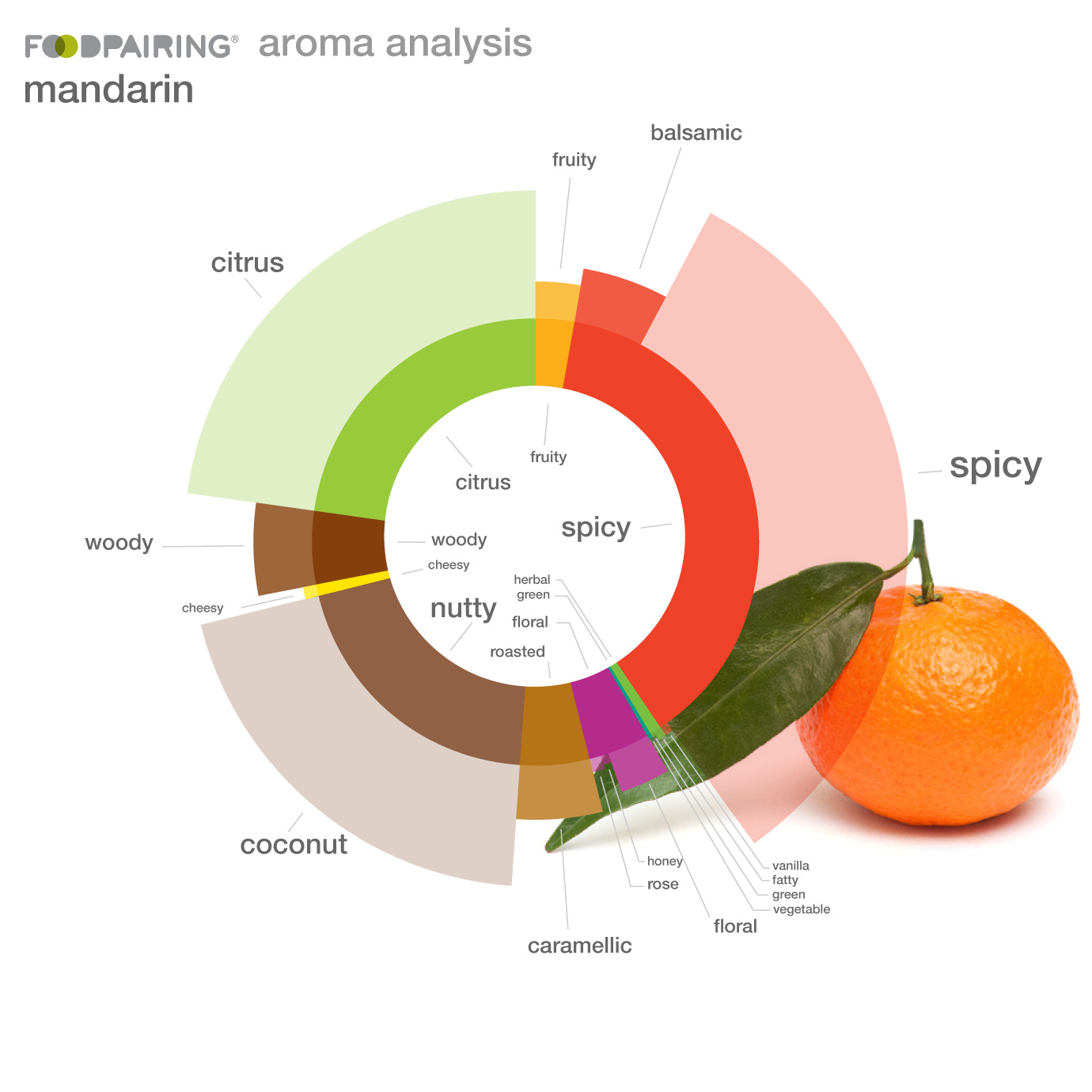

Was this the answer I was looking for? The key to every flavour…? A company called 'Food Pairing', which has also authored 'The Art and Science of Food Pairing', have gathered together a library of ingredients and matches, categorising the aromas (and their responsible molecules) into 14 types: Fruity, floral, herbal, caramel, nutty, spicy, animal, citrus, green, vegetable, roasted, woody, cheesy and chemical. Phew. So the story goes: Heston Blumenthal put together white chocolate and caviar and wondered what on earth was going on. With the help of a friend, they looked up the two ingredients and realised they shared a flavour molecule. The library and reference book is an extrapolation from that.

It's a fascinating and alluring system, but how can we apply this information? The research confirms a relationship between well-known pairings like ginger and coconut (both scoring aroma compound points for fruity and citrus), roast pork and plum, hazelnut and chocolate, and eggs and bacon; it also suggests a host of potential links that are unlikely to come to mind.

From raspberry and chorizo to feta and papaya to passionfruit and aubergine to mascarpone and doenjang (fermented soybeans) to dark chocolate and grilled lamb… how useful is it for us to know that these seemingly random pairings share compounds?! And what are we supposed to do with this information? I contacted Dr Rachel Edwards-Stuart, a London-based flavour expert and food scientist to get deeper into this topic.

A conversation with a flavour expert

Rachel has a remarkable story. I mean, find me another person with a degree in biochemistry who has also spent ten months studying the science of potato salad in a laboratory?! After graduating from Cambridge University, Rachel sought to find a way to blend her higher education with her 'higher purpose' (cooking). She contacted renowned molecular gastronomist Dr Hervé This, resulting in the aforementioned potato salad sojourn. She followed this with a PhD at Nottingham University, co-sponsored by Heston Blumenthal, no less, on the Science of Cooking, spending three years developing flavour and texture innovations for Blumenthal's restaurant 'The Fat Duck'.

During this time, Rachel took a particular interest in flavour perception. This has lead her to a series of a series of teaching, consulting and lecturing roles worldwide - in kitchens and classrooms alike. I was fortunate enough to ask her about the world of food pairing and what we can learn from it (and what might not be so helpful).

On whether matching flavour molecules is a reliable way to put ingredients together, Rachel immediately reminds me that "whether things go together or not is completely subject to personal opinion", offering that no one has the power, not even science, to tell people what will go well together. "You can't have a scientific equation that ultimately tells you what people will like." Well, darn!

So what, if any, relevance does sharing aroma molecules have? A research paper exploring the principle, commissioned by the Food Pairing company, revealed that ingredients in Western recipes tend to share aromatic affinities while East Asian food culture does the opposite. Analysing some 50,000+ recipes, the research revealed that in recipes originating from North America, a greater number of shared aroma compounds between two ingredients increases their likelihood of appearing. In contrast, in East Asian recipes, a shared number of aroma compounds diminishes the likelihood of ingredients being used together.

Rachel explained that the key to unlocking various combination is more about the context; While she wouldn't treat a common aromatic compound as gospel, she suggests it could be useful "for inspiration, like a writer's block tool." A few years back, Rachel developed a cocoa and brie topping for a consultancy gig after identifying similarities between the two ingredients via an aroma network tool. Though she thinks it was unlikely she’d have put the two together if it hadn’t been for the shared compounds, the combination still had to go through rigorous testing, adjusting and rounds of feedback. What works, and doesn’t, when it comes to flavour is simply not an exact science.

Although it would be convenient, there isn't a formula for flavour, no rules we can apply to everything, and no one-size-fits-all approach that will solve it all. And though 80% of our perception of something might be aroma, the 20% taste is fundamental - we need to balance salt, acidity, fat and sweetness to dictate the pairing. Sure, cheat codes like linalool in blueberries exist, but they may be the exception, not the rule. It's ultimately how we express these ingredients and not expect the aromas to do all the work.

Famous combinations

So, what of the most iconic combinations out there, what has landed them in the hall of fame? Rachel suggests that it could be down to exposure. "If I was to do a blind tasting of beef and horseradish now, I don't know that that would make it through. We're just so used to pairing them now. The same goes for turkey and cranberry." She explains that the theory goes if you try something at least 15 times, you learn to like it. This is often applied to fussy eaters - you must break down the barrier that the food just isn't scary.

Rachel also suggests that our habits can change and be influenced by the people we spend time with. "So much of what you end up liking is based on your upbringing and experience," she explains.

How does Rachel, a professional flavour expert and consultant, find combinations? "A lot of the decisions I make are based on texture and taste," she explains, as well as paying close attention to the trigeminal sensations, the part of the nervous system that provides sensation to heat (chilli, spice) and temperature."You wouldn't pair horseradish and chilli. It'd be a total trigeminal overstimulation nightmare!" she explains. Rachel is, of course, a supertaster, a term coined for members of the population hypersensitive to taste (around 25% of people) due to a higher number of taste receptors. (Note: another approx. 25% of people are considered 'non-tasters' with half the average amount of taste receptors!).

On the relationship between certain ingredients, like banana and clove (which share eugenol), Rachel reminds me not to underestimate the power of suggestion. "One of the things I do at [chef workshops] is to offer lemon-lime flavoured water. One is dyed yellow, and one is dyed green." It's no surprise that the yellow one is always thought to taste more lemon-y, while the green one is way more limey. So, that means if someone tells you their banana cake is ‘way more banana-y’ because of the cloves, before you’ve even tried it, perhaps your brain will find a way to fill in all that extra flavour!

So… what does it all mean?

Ultimately, it all comes down to your palate, literally. There is huge variation between our own sensitivities to the five tastes, while 30% of our olfactory receptors differ from person to person thanks to genetic variation, causing us to all perceive aromas (and flavour!) differently. I think this is why we find affinity with certain chefs, restaurants and books. By looking for people with similar taste and flavour sensibilities to us - that’s a version of flavour matching I can really get on board with.

Before we get onto the recipe, this week’s newsletter had quite a lot of research and paper reading, all of which I found SO fascinating. Click here for the bibliography and further reading!

Pairing pears

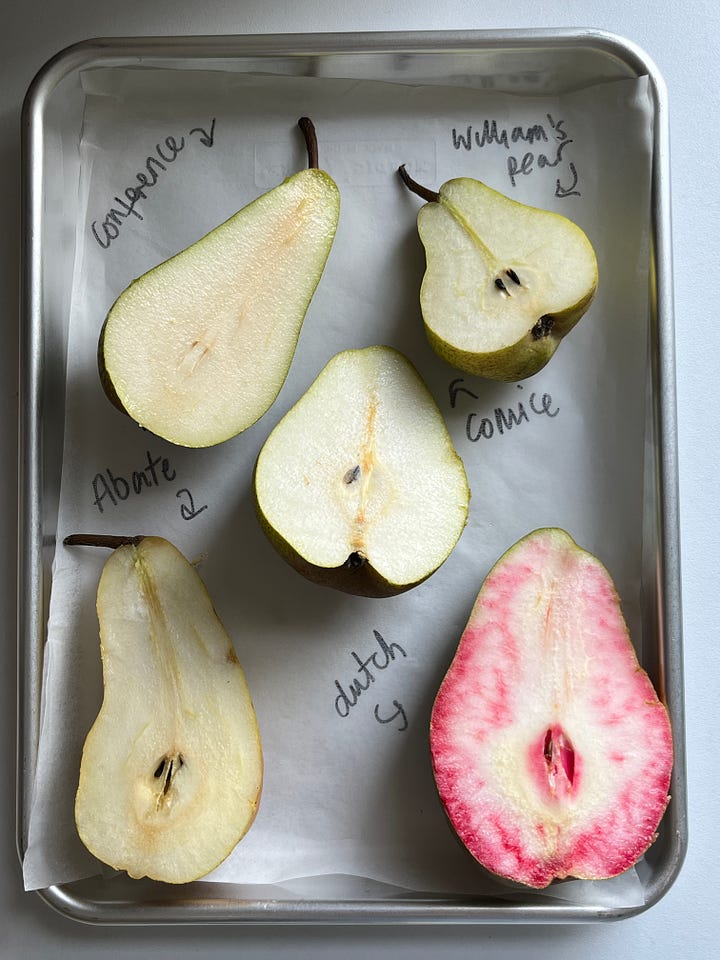

I love pears. I admit they have a subtle flavour and think much of my enjoyment of them is down to the texture. Famously difficult to capture at perfect ripeness - personally, I'm not a cruncher when it comes to pears - we are in peak season at the moment. Unlike apples, pears continue to ripen once they are off the tree, meaning we have a good supply of them all winter. Of course, some fare better in cold storage than others, but it makes pears a fresh friend for the whole of the season. For poaching and baking, I love the dependable conference.

So, what makes a classic pair for a pear? I asked the question on my Instagram story, and there were a few popular answers: Hazelnuts, apples, cardamom, chocolate, ginger, vanilla, rum, cheese (goats, blue) and honey were all suggested multiple times. And I agree, all of those combinations sound great. Is there a rhyme or reason? I consulted the food pairing book to find out if there were any particular shared aromas or whether these popular matches were just a coincidence.

According to the 'Food Pairing' book, 'Ethyl Decadienoate', also known as 'pear ester', is the dominant aroma molecule in pears. It has been detected in apples, passionfruit and bananas. It also suggested that pears share compounds with speculoos biscuits, dates, orange, rosemary, vanilla and oats.

When researching pear aromas, I also came across 'isoamyl acetate', which is sometimes referred to as 'pear oil' or 'banana oil' - though it doesn't actually naturally occur in pears, it's often used in pear-flavoured things, like pear drops or juicy fruit, along with banana flavoured goods, like foam bananas and milkshake powders. A similar compound 'ethyl acetate', is the most common 'ester' found in wine and is also used in pear drops. It's no surprise, then, that wine is such a popular poaching match with pears. Taking this as inspiration, can we use this as a jumping-off point to find other matches? Isoamyl acetate is found in beer, cider, rum, cognac and whisky, to name just a few.

Over on KP+

On KP+, I’ve taken a few of my favourite pear pairings - hazelnut, ginger, chocolate - and thrown them together into one delicious biscuit: Hello to my sticky pear shortbreads. We start by making a jammy pear reduction which nestles into a tender-rich dough that, remarkably, doesn’t spread at all. The pear cutter is extra, of course - these would be adorable in little rounds:

Poaching

One of the classic ways to prepare pears, of course, is poaching. Perhaps its old school to be presented with an entire pear, standing tall on a plate, without much dressing. But I think it’s a thing of beauty. I’m shocked I’ve never covered it on the newsletter, to be honest!

Poaching is a gentle method of cooking where we submerge ingredients in a liquid - often flavoured - and simmer until cooked to our liking. Poaching should take place at a low simmer, and the time it takes will depend on whether you are cooking pears whole or in halves (or smaller!). The best way to judge if the pears are ready is by piercing the flesh with a sharp knife. The pears will also look shiny, plump and translucent.

Poaching is a gentle transfer of the water and sugars inside the fruit and the water and sugars in the surrounding liquid, leading to the softening of the fruit's texture and an exchange of flavour between the fruit and the poaching liquid. As a result, the flavour of the liquid is left like a signature. The most straightforward way to see this is in the case of red wine-poached pears - you can't argue with the crimson colour.

Once poached, you can use the fruit in a multitude of ways: Since the pear is already cooked, the fruit is more stable when it comes to water loss. It won't 'wet the bed' when introduced into other recipes. You can poach pears up to five days in advance with no ill returns

How to pick a poaching liquid

There's a multitude of combinations for poaching liquids, and it all depends on what the next 'steps' for the pears are. While wine is a classic (with a little lemon juice, bay leaves and cardamom, it really sings), this week I fell in love with a fruity pale ale poaching liquid. Sent to me by my wonderful friend Ben at The Kernel Brewery (along with a bunch of barley malt I was considering for an infusion), the interplay of bitterness - shout out to last week's newsletter, hi Alexina! - with added vanilla lets the subtlety of pears shine. I’m not a beer person, so this revelation has pretty much shocked my to my (pear) core.

Cider would also be a good shout, but I do think apples and pears often get bundled together when they should be allowed to shine on their own. Another favourite liquid is tea - you can go wild here. Jasmine is wonderfully fragrant, while chamomile and Earl Grey make the most of the floral notes. While 1:2 sugar to liquid is a good starting point, I find pears are easily overpowered by sugary liquids, and I prefer 1:3.

Poaching sauce

I’d always suggest taking the chill off the pears before serving. You can do this for a few minutes in the poaching liquid as it reduces. You can spoon the poaching liquid as-is on top of the pears for a simple dessert, though reducing it and bubbling with fat - butter or double cream - makes something that feels really special through low effort. I can't argue with that.

For today’s recipe, I suggest adding ginger to the final reduction so we end up with a slightly spiced sauce, as well as a tiny drip of vinegar to help take the edge off the sweetness. A little fresh pour of beer right at the end adds a hoppy bitterness that is a fun foil to the syrupy sauce. Oh and serving with additional cold cream or ice cream is always a good idea.

Beer poached pears with ginger butter beer sauce

Serves 4

I used The Kernel Table Beer Pale Ale. According to my friend Ben, who is a brewer at the kernel, the tasting notes are “Light body, malty, with a bitter finish that doesn't dominate. Tropical fruits, oranges and citrus.” YUM!

Active: 10 minutes

Total: 1h (not including optional overnight rest)

Poaching ingredients

4 x Firm pears. I used conference.

600ml Fruity Beer – I used The Kernel which is a pale ale

200g Caster sugar

20ml lemon juice

4-6 strips orange peel, about 2g each

1 x vanilla pod, seeds scraped

Ginger butter beer sauce

400ml poaching liquid from above

20g piece of fresh ginger

25g Butter

¼ - ½ tsp Flaky salt

¼ tsp Cider vinegar

30-50ml beer (the same as before, if possible)

Method

Heat the beer, sugar, lemon juice, vanilla and orange peel together gently and bring to just below a simmer in a small-ish saucepan. You want to make sure the pears all fit and will be covered by the liquid. I like to do a test run with the pan by placing the unpeeled pears into the pan then cover with 600ml water to see if it’s a good fit!

Peel the pears, keeping the stalk intact where possible. If you are serving singular standing up pears, trim the base so it can stand up on its own. Place into the poaching liquid. If desired at this point, cut the pears into smaller pieces and remove the seeds and core– halves are lovely.

Make a cartouche – this is when you cut a paper circle with a little hole in the middle to let the steam out. Place it on top of the pears. If they are bobbing around, you can place a spoon or fork on top to help keep them submerged. If the fruit isn’t fully submerged, it might turn brown in places.

Bring the liquid to the most gentle simmer – just a few bubbles here and there. Poach the pears until you can pierce the flesh with no resistance. If needed, you can flip, turn and rotate the fruit. You can test this with a sharp knife or a toothpick. For whole pears, this might be 30-40 minutes, but I start checking after 20. For halves, you’re probably best to check after 15 minutes.

Turn off the heat. At this stage, you can leave the pears to cool in the syrup completely and store in the fridge for 5 days. If you want to eat them now, move the pears to a dish and and cover loosely to keep warm.

To make the ginger butter sauce, divide the poaching liquid. Scale 400ml of the liquid and put back into the pan. Pour the rest of the warm liquid over the resting pears.

Add the fresh ginger then turn the heat up to medium high and bring the liquid to the boil. Boil hard for 10-15 minutes or until it is very thick and syrupy and reduced to approx. 1/3 of the weight, about 120-140ml. Whisk in 25g of butter with the flaky salt then bring to the boil. Boil for 1 minute until well combined then finally whisk in the cider vinegar and a little beer, to taste. Check the flavour of the sauce – beware, it’s hot!!! Leave to cool slightly and thicken for a few minutes.

To serve, place the warm pears in the middle of a plate. Spoon the warm sauce on top and add extra cold cream, if desired.

Hi

Fun with softserve!!

This is me @francisfrancissoftserve

Wish I could come to England and try it. My husband is from London so I'm only visiting over Christmas to see his family. Do you have any plans for a pop up during the holidays?

Kind regards Pernilla

Such a good and comprehensive post - thank you! Love,that you mentioned tea🌱 I poach my pears in Oolong or Milky Oolong tea.