Hello,

Welcome to today's edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here! With this heat wave, there was really only ever one option for this weeks newsletter…

Telling the story of ice cream and sorbets is not easy, but it is fun. Frozen desserts really are the most scientific out there. Today I'll guide you through the general theories behind it, finishing with two sorbet recipes - no ice cream machine required! Although I'll share the technique and experiments on no-churn ice creams below, the recipe for no-churn apricot ice cream sandwiches (with a brown butter oat biscuit and passionfruit) is available on KP+, as well as a link to my sorbet calculating spreadsheet.

What's KP+? Well, Kitchen Projects+ aka KP+, is the level-up version of this newsletter. It only costs £5 per month, and your support makes this newsletter possible. By becoming a member of KP+, you directly support the writing and research that goes into the weekly newsletter and get access to lots of extra content, recipes and giveaways, including access to the entire archive. I really hope to see you there:

Love,

Nicola

The age of the ice cream machine… or not

'This year', I say, every year, 'this year will be the year I buy an ice cream machine.' So guess what, my friends? Once again, it is NOT the year.

I'm not sure why I'm so hesitant to buy one - they are reasonably affordable, providing you love ice cream, and would surely give you endless returns for your investment. I, like most of us, have limited space in my kitchen. Despite spreading out over a floor-to-ceiling shelving unit and a butcher's block with racks and drawers, a set-up that shamefully sprawls into the living room, I still can't find room in my house - or heart - for an ice cream machine.

Ice cream machines work by churning / aerating mixtures whilst freezing them. As the mixture freezes, the churning action breaks down large ice crystals, producing that creamy smooth texture we know and love. At the same time, air is trapped in the network of crystals, which increases volume. It's this agitation that prevents iciness. Ever put a slightly melty tub of ice cream back into the freezer, only to come back to it later days later and find it… crunchy (not in a fun way?) That's what happens to ice cream base that is frozen without agitation. So, though an ice cream machine is a fantastic tool, I don't have one… so THAT method is out.

So, what are the other options? Well, I *do* have a food processor. And that does a pretty good impression of a pacojet. What is a pacojet? The pacojet was invented in the 90s and has fast become a chef's favourite tool - it works by very finely shaving frozen blocks of ice cream into very thin sheets - basically pureeing it. This process has been called, by the inventors of the pacojet, 'pacotizing'. Virtually anything can be effectively pacotized - even a poorly balanced ice cream recipe would come out creamy and beautiful. So, although your food processor at home might not be able to process bases quite as finely, it does a pretty good job!

Got no food processor? You can always try the classic 'no machine' method - freezing your ice cream in a home freezer, then removing it every 30 minutes and agitating it with a fork until it is smooth and almost entirely frozen. Basically, you're acting as the lo-fi churn in an ice cream machine. Also, the process takes about 4 hours, compared to about 15-20 mins in a machine.

Of course, you could always make a parfait or semifreddo (recipe here from last summer!), but I'm happy to tell you there's a whole world of frozen desserts at your fingertips. For today's newsletter, we'll run through the defining factors of churned ice creams and sorbets, as well as the science of no-churn ice creams too. I'll do my best to give you an overview, from the ingredients to the ratios.

Let's do this.

Understanding the ‘stuff’ of ice cream and sorbet

Most frozen dessert formulations have common ingredients. The base is either fruit puree for sorbet or milk/cream for ice cream. It may be enriched with egg yolks for flavour and its emulsification qualities (it helps bind everything together and give a firmer texture to your finished product). There is ALWAYS sugar, for sweetness and for its crucial role in 'scoopability'. Then, finally, there are flavourings - this is anything that doesn't affect the basic structure of the ice cream. From infusions to jammy ripples to solid chunks of chocolate. But what is going on with all these ingredients? How exactly do they work together to give you a dreamy frozen pud?

And what of no-churn ice creams? Have you ever wondered why condensed milk is the bedrock of so many no-churn ice creams? I did too. And after years of pondering/accepting, I think I've finally worked it out. To put it inelegantly... It's full of 'stuff'. This 'stuff', meaning sugars, milk solids and fat, helps create a smooth frozen texture as it interrupts the rough, ice crystal structure that water forms below 0c. To understand how important this 'stuff' is, we must first understand how ice cream is made, no matter the method.

Classic ice cream is churned - churning is the process of agitating a mixture whilst freezing. As ice crystals form as the temperature is lowered, they are broken up and dispersed into smaller and smaller crystals, resulting in smooth ice cream. For no-churn ice cream, as in ice cream that won't get agitated as it's frozen so won't benefit from those ice crystals being broken up into smaller and smaller fragments, we are putting that texture entirely into the hands of the ingredients/formulation. This is where all that aforementioned 'stuff' comes into play.

If left to its own devices, water freezes at 0c into a hard icy block. This happens because the low temperature causes the molecules to slow down so much that they settle into place, forming crystals as they line up. But these aren't nice, smooth crystals; quite the opposite - these are jagged, stabby crystals with pointy tips that 'crunch' when you eat them. Just look at these super close-up images! Deadly! As well as this, you'll know from making ice cubes that water goes from clear to cloudy. That's because water will freeze as soon as it passes the 0c threshold. Since this will be from the outside inward, impurities and air bubbles get pushed to the middle.

Ice fighting tactics

So, you can tell that free water is a total pain - free water is the enemy of smooth frozen desserts and needs to be occupied. Fortunately, there's a team of icy-fighting ingredients at your disposal. Let's go deeper.

Fat, usually provided by double cream or yolks, is essential because it coats ice crystals, preventing them from expanding and creating those jagged networks, though it does need the help from sugar/milk solids, which we'll cover next. As well as this, fat is essential for mouthfeel, melting as it hits our palate, coating our mouths pleasantly, and adding its own flavour. Since fat is such a good carrier of flavours, our experience of eating a frozen dessert changes depending on the proportion of fat to other ingredients - sorbet, which is fat-free, has an immediate, intense flavour that is very 'clean', whilst ice cream tends to have more of a slow-release.

When you freeze double cream, the water and fat will separate, clumping together in their respective tribes. As the water freezes, the jagged crystals literally splice through the milk fat - brutal, right? From a texture perspective, it takes much longer to go solid because it is only half water. So, at 0c, only half of the mix will be frozen, so it will be semi-solid. It's not until you get to temperatures of -30c that over 90% of the mix has been converted into solid, so the double cream will be as solid as ice.

There can be, of course, too much of a good thing - overly fatty mixes may split when agitated, leaving chunks of solid butter throughout the ice cream. Since no-churn ice cream is not agitated after the initial mix, the risk of the emulsion breaking is smaller, so it can have a higher proportion of fat than a standard churned ice cream.Milk solids are basically leftovers once all the liquid is removed from dairy. These solids refer to a few things - fat, as above, but protein (whey, casein), lactose - a sugar - and a small number of minerals. Solids are important in ice cream because they reduce iciness by absorbing water - this prevents water from freely moving to hang out with other water and form chunky ice crystals. Fruit solids, basically fibres, are also key and have the same role

Sugar - in the form of sucrose - is a key part of the story, too. Beyond sweetness, sugar has several roles - firstly, it adds 'body' aka solids (as mentioned above). Secondly, sugar determines the softness of the ice cream - it does this by depressing, i.e. lowering the freezing point. It is also known as an antifreeze.

Freezing point depression is a term you often hear in ice cream making. The temperature that a liquid turns into a solid is the 'freezing point'. With water, that's 0c. So, 'depressing,' ie. 'lowering' the freezing point, means it needs to be colder for a liquid to turn into a solid. How much the freezing point is depressed aligns with how 'soft' or scoopable the ice cream is when frozen.

Sugar effectively lowers freezing points because it totally disrupts the structure. Sugar, dissolved in water, prevents water from making the hydrogen bonds required to become solid by literally getting in the way - without hydrogen bonds, liquid water cannot form ice crystals! Instead of forming hydrogen bonds with other water molecules, they form hydrogen bonds with sugar. Sugar molecules physically interrupt the structure, holding the mixture together but preventing ice crystals from getting bigger and, therefore, crunchier on the palate!

It’s worth noting that salt is also an antifreeze, but it can't be added in large amounts due to its potent flavouring abilities. Alcohol is also an antifreeze - ethanol, the compound found in wine, beer, spirits etc., doesn't freeze solid until -114c, so adding a portion of booze into your frozen desserts can also provide softness.

Why condensed milk works in no-churn ice cream

The type and amount of 'stuff', including sugars, fat and milk solids, vary between dairy products. Whole milk, for example, has low fat (3%) but comparatively high lactose (5%) and protein (3.4%). Double cream, on the other hand, has 45%-50% fat, but very low lactose and whey, less than 1.5% each. Our special ingredient condensed milk has 8% fat, 7.5% whey, around 12% lactose, and a big chunk of added sucrose, about 40% depending on the brand.

So, understanding how packed condensed milk is with ice disrupters is the key to its success as an ingredient in no-churn ice cream. No-churn ice cream utilises milk solids and fat to provide a smooth texture without the need for agitation, whilst churned ice cream has a higher proportion of water - this has a lighter mouth feel and airiness we know and love from classic ice cream. BUT, it requires the crystals to be physically broken down during the freezing process to work.

A basic formula for churned ice cream is: fat + sugar + milk solids + water + agitation = smooth ice cream. For no churn ice cream, it's more like more fat + more sugar + more solids + less water = smooth ice cream.

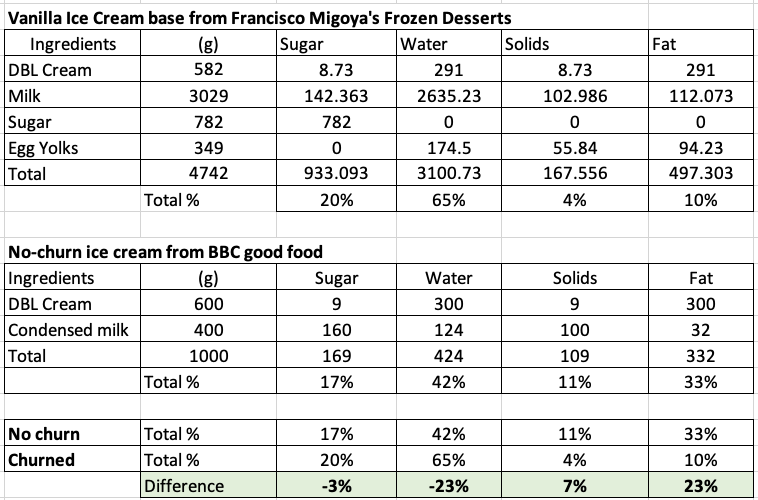

Let's compare a 'classic' vanilla ice cream to a 'classic' no churn recipe:

There is 23% less water in the no churn, 3% more sugar, 7% more solids and a massive 23% more fat! So, when agitation is involved, we can afford to have more water (stabby ice crystals!) in our formula and less fat which may, when churned, split out of the mix. As well as this, we are also relying on more milk solids for that silky mouth feel.

The deal with fruit

Fruit is rich with flavour but not much else! Most fruit is at least 80% water - the rest comprises naturally occurring sugars and solids (fibres, etc). Being majority water, it is not naturally predisposed to being a lovely smooth frozen product, so it needs a lot of help to prevent it.

Since sorbet is fat-free, we can't rely on butterfat or lactose's ability to temper those crystals. That means we need a higher proportion of solids (in the form of fruit fibres) and sugar to get a non-icy product, predominantly sugar. For context, sorbet needs around 20%-30% sugar in the final product, whilst ice cream has around 10-12%. As we explore in KP+ today, no churn ice cream needs even more.

As well as sugar, the 'creaminess' of sorbet is determined by those all-important solids. Fruits high in fibre, like mangoes, or high in pectin, like stone fruit and strawberries, are already equipped with enough body/solids to make a rich-textured sorbet. Pectin improves viscosity and like sugar, helps to decrease the size of ice crystals.

Fruit is not a natural bedfellow for no-churn ice cream with all its water content. However, with the help of a spreadsheet, it's all possible. Over on KP+, I'm sharing a recipe for apricot no-churn ice cream as well as the perfect cookie to eat it with - brown butter oat cookies. Who doesn’t love an ice cream sandwich?

Exploring the ratios

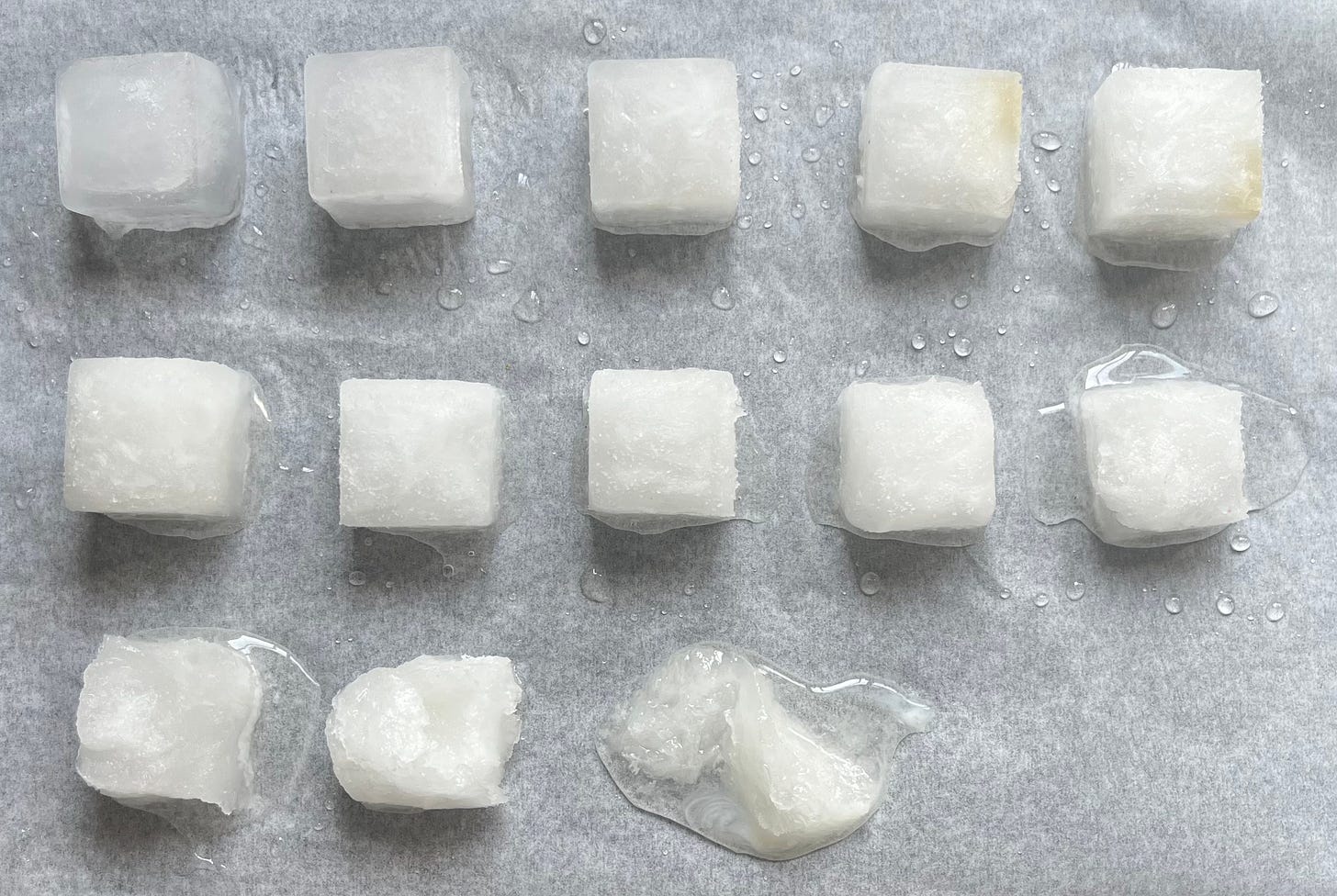

So, now we know what the key factors are. But what are the limits of the ratios? I mixed up a few tests to find out.

The role of sugar

As we know, sugar is a critical factor for texture (and more practical than salt and alcohol as an antifreeze), so I tested the effect of sugar on water, strawberry puree, milk and cream. Many recipes warn of adding 'too much' sugar, so what is the limit? At what point does the sugar interfere so much with the structure of those four products that it simply cannot set?

Sugar + water

As you can see, the water can hold pretty good shape all the way up to 90% sugar to water concentration. After that, it is pretty much slush and reverts to a syrup very quickly. I used a table knife to slice through the tests - at 40% sugar, I could easily slice through it with very little resistance. This makes sense since the guideline for sorbet is 25%-30% sugar.

Sugar + strawberry puree

The fruit puree was more sensitive to sugar, probably because there were already existing sugars and fibres interrupting the water's ability to freeze hard. At 20% sugar, you could easily slice through with a table knife, and by 40%, it was ‘callipo’-y! Since the strawberry puree already has about 9% naturally occurring sugars and fruit purees, which interrupt the water freezing solidly into ice.

Sugar + Milk

Since milk is around 87% water, it, too, is more sensitive to sugar - it takes less sugar to interfere with the freezing since the solids/sugar are already playing a part. Above 50%, it was pretty squishy. It was easily sliceable at 25% sugar to milk.

Sugar + Cream

This was fascinating - the range of sugar cream can take before being utterly un-freezable is below 50%. This is because there is really only 55% water to begin with in cream and lots of fat to interrupt the ice crystals forming. It was also incredibly smooth - the 10% - 25% samples were DELICIOUS as well. I used this info to figure out a super easy no-churn ice cream on KP+ - check it out here.

Effect of alcohol

As we know, alcohol is an antifreeze - this is useful for managing texture and helping scoopability. Many recipes warn against adding too much alcohol should your mixture not set. But how much is too much?

I was surprised at how well all of these held up - those grave warnings of too much alcohol playing havoc with the setting are, I think, a bit dramatic. Although it was quite slushy at the higher proportions, it wasn't totally useless.

The final word on balancing sorbets

One of fruit's most charming but annoying things is the year-to-year changes. I still remember the flat peach I ate in 2015 - I have no idea where it came from, but I've never had a better one. When it comes to fruit, we are at the mercy of nature. Many kitchens choose to use commercially made fruit purees - Boiron is a popular brand - to not deal with the faff of the mercurial fruit crops. I get it! So, how do we manage this?

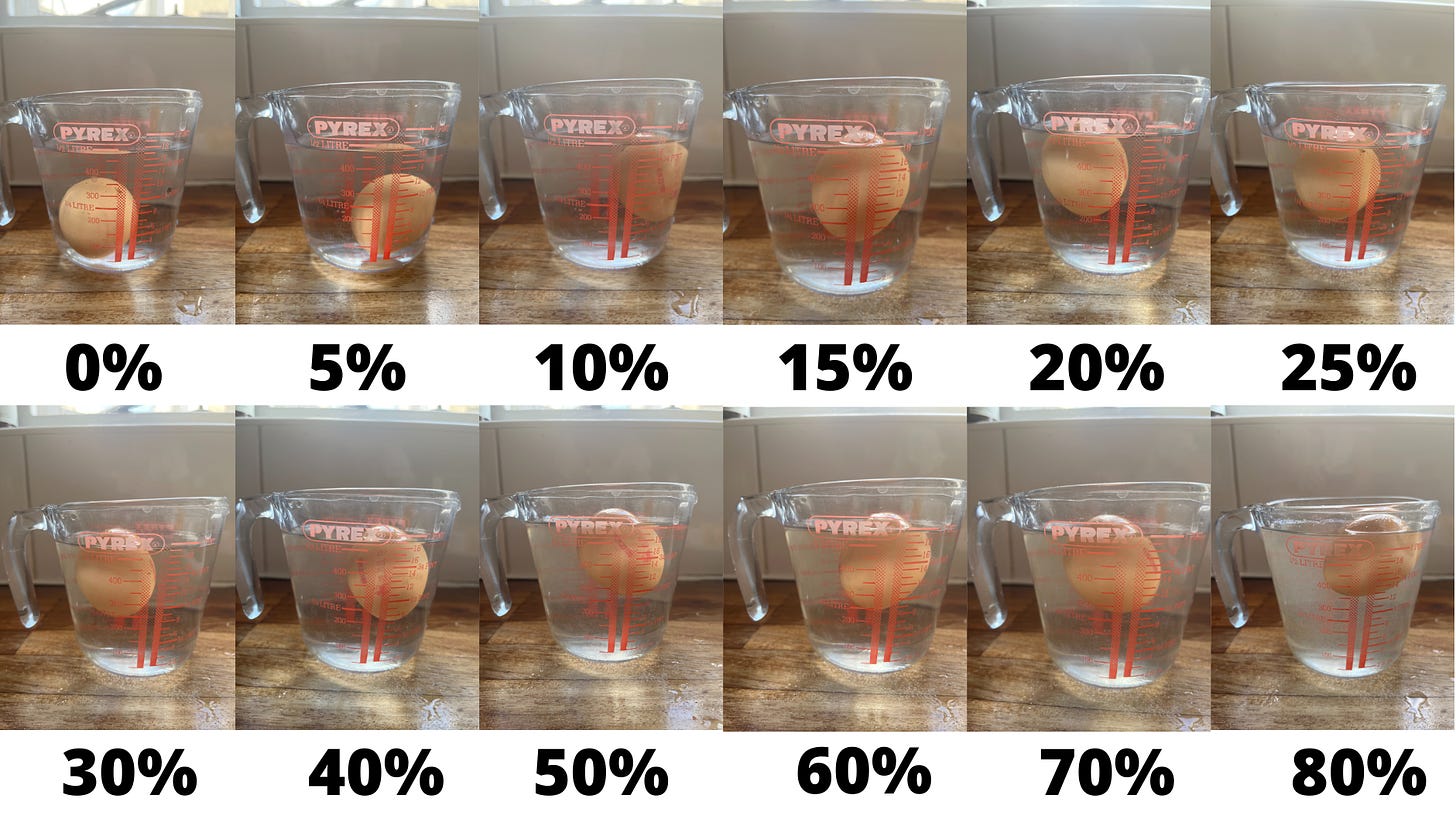

One tool in ice cream kitchens is the refractometer which measures sugar concentration in 'brix', which means how dense the liquid is with sugar (1% sugar = 1 Brix etc.). This is handy if you are working with market fruits - the sugar from year to year may change between crops - you could simply puree your fruit and then add sugar until it reaches that magic 25%-30% sugar content, which gives you a thick creamy sorbet. Less accurate, but still legit, is the egg trick. A fresh egg is filled with air so when there's around 25% sugar concentration, the egg will float and a 1inch section of the shell should be visible from above. This is sort of helpful - it won't tell you if you've got too much sugar, but it will give you a pretty good indication you're in the right place. I put this to the test:

As you can see, as the sugar concentration increases, the egg does float higher and higher. However, the discernible difference between a palatable 25% and an OTT 80% isn't that significant. So, use this trick, but with caution!

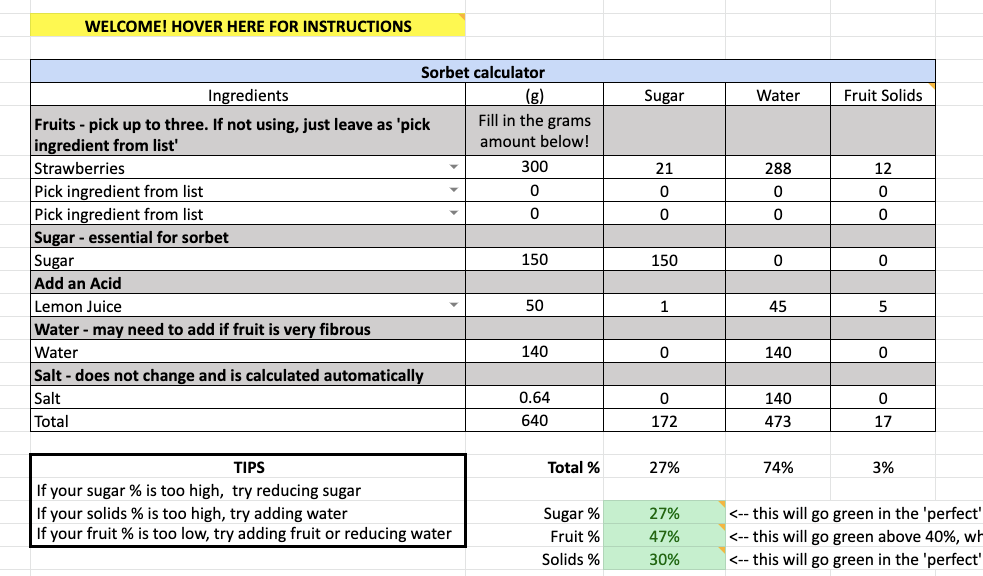

Prefer something a bit more technical? Well, for KP+ subscribers, I've built a sorbet calculating spreadsheet. Using information from Francisco Migoya's 'Frozen Desserts' book and Harold McGee's 'On Food and Cooking', you can build your own formulations! Click here to subscribe and access the spreadsheet of joy:

Want help making your own sorbet recipes? Join KP+ to access my handy sorbet calculator!

Alright let’s make them!

Roasted strawberry and Watermelon sorbet

Makes around 500g sorbet, or 1/2 a litre

For the first of today's recipe, I mix sugar directly into the blended and passed fruit. Depending on the fruit's water content, some recipes may benefit from making a sugar syrup or adding water. Fortunately for watermelon and strawberries, there's already plenty of water for the sugar to get busy with. I've also included a formulation for straight strawberry sorbet - you'll see here I've had to add more lemon juice/water to up the hydration. And, as always, don't forget to add a tiny bit of salt!

Roasting the strawberries intensifies the flavour - the watermelon is a calm backdrop to the jammy strawberry flavour. Add lemon juice to taste, but at least 20ml.

Roasted strawberries ingredients

130g strawberries

13g caster sugar

Rest of sorbet ingredients

250g watermelon (weight once juiced and passed through a sieve)

All roasted strawberries from above, blended and passed through a sieve to make 125g

100g caster sugar (can be reduced to 90g, taste your fruit it may be sweet enough)

30g lemon juice

1/8th - ¼ tsp salt

Method

First roast the strawberries - add sugar to strawberries and toss, then roast in a 150c oven for 30 minutes until shrivelled and syrupy. Leave to cool then blend all and pass through sieve

Puree watermelon then pass through a sieve to remove seeds / excess pulp

Mix together the strawberry puree, watermlon puree, sugar, salt and lemon juice. Check for seasoning and adjust if needed

Freeze in a leak-proof freezer bag (I like this because you can get it to lay super flat/thin and it freezes faster!) or container for 6-8 hours until completely solid

Break into chunks, then blend in a food processor until you reach a scooping consistency - use the warmth of your hands around the side of the bowl to help if needed

Serve immediately or return to the freezer for several hours. You may need to reblend after 24-36 hours for the best texture

If you have no food processor, use the classic 'no machine' method - freezing your ice cream in a home freezer, then removing it every 30 minutes and agitating it with a fork until it is smooth and almost entirely frozen. Basically, you're acting as the lo-fi churn in an ice cream machine. Also, the process takes about 4 hours, compared to about 15-20 mins in a machine.

Pure strawberry sorbet

Makes around 500g sorbet, or ½ a litre

For this recipe, the strawberries need a little extra water in the form of a syrup.

300g strawberries (weight once green stem removed)

150g caster sugar (can be reduced to 140g, taste your fruit it may be sweet enough)

50g lemon juice

140g water

¼ tsp salt

Method

Dissolve sugar and lemon juice in water with salt

Blend strawberries then pass through a sieve to remove pulp/seeds

Mix together sugar syrup and strawberry puree well. Taste for seasoning and adjust if needed

Freeze in a leak-proof freezer bag or box for 6-8 hours until completely solid

Break into chunks, then blend in a food processor until you reach a scooping consistency - use the warmth of your hands around the side of the bowl to help if needed

Serve immediately or return to the freezer for several hours. You may need to reblend after 24-36 hours for the best texture

If you have no food processor, use the classic 'no machine' method - freezing your ice cream in a home freezer, then removing it every 30 minutes and agitating it with a fork until it is smooth and almost entirely frozen. Basically, you're acting as the lo-fi churn in an ice cream machine. Also, the process takes about 4 hours, compared to about 15-20 mins in a machine.

Thanks for reading! This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. The best way to support my work is to become a paid subscriber and help keep Sunday’s free for everyone.

Yet another brilliant 'deep dive', thank you! The effort and wonderful 'nerdiness' that you put into KP is just great. Also, KP+ is the best use of £5 a month I've ever found and I've been around a very long time....

The detail on this is so great Nicola. Fantastic job