Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. It’s so wonderful to have you here.

Today we complete our journey into puff pastry together with a deep dive into a curious type of puff: Inverted. I’ll be showing you how to get the best out of your puff when you bake it and put this inverted style head to head with the classic.

Over on KP+, I’ll show you how to turn your caramelised puff sheets into a beautiful Rhubarb and Custard Mille Feuille. Subscribing to KP+ costs just £5 and you get loads of extra content whilst supporting the writing of this newsletter, so please click here to check it out:

Lots of love

Nicola

Flip and reverse it

Inverted puff pastry is the definition of ‘trust the process.’ When you embark on the journey of inverted puff with me, you’ll probably be wondering what on EARTH this forsaken stuff is. I mean, wrapping butter around dough? It sounds both ridiculous and amazing, I’ve always thought.

In case you’ve never come across it, inverted puff pastry flips the pastry lamination process: First, butter is combined with flour to create a buttery block, which is wrapped around a dough block. Lamination then continues as normal. Sounds weird, I know, but there really is a method to the madness.

If you google ‘inverted puff pastry’ and ‘why’ (this is something I’ve done quite a lot, to be honest) you’ll find articles that tell you that it makes a ‘lighter’ or ‘more buttery’ or ‘richer’ or ‘flakier’ pastry. And believe it, sure! But WHY does it make a ‘lighter’ or ‘more buttery’ or ‘richer’ or ‘flakier’ pastry? I’m going to do my best to investigate this today and compare the OG puff and the Invert Puff and see where we get to.

As well as this, I’ll be showing you one of the best ways to eat puff pastry: Caramelised and compressed. We’ll go through the best practice on baking it and getting the best golden sheen.

Over on KP+, I’ll show you how to take your puff and turn it into a beautiful rhubarb and custard mille-feuille:

Later on in the week on KP+, I’ll share my recipe for the most delicious arlettes - ultra caramelised, spiced biscuits that blow palmiers out the water (no offence palmiers, but arlettes are kind of a big deal).

Ok, let’s go.

Head to head

To figure out the whole classic vs inverted thing, I made two doughs - a classic puff and invert puff - so we can compare the two side by side. To create my invert puff recipe, I simply played around with my classic puff pastry recipe, trying to keep it as similar as possible to the original.

To start, I moved a proportion of the flour to the butter to make the butterblock ratio 75% butter and 25% flour. I then adjusted the hydration of the dough block to be in line with the classic puff (the detrempe has 40% water to flour, bakers percentage). Since the dough block is now smaller, quantity of water required to mix the detrempe is smaller, too. Here’s my final recipes, side by side:

As you can see, the side by side numbers for a 500g block hasn’t changed too radically, the numbers have just hopped around a bit!

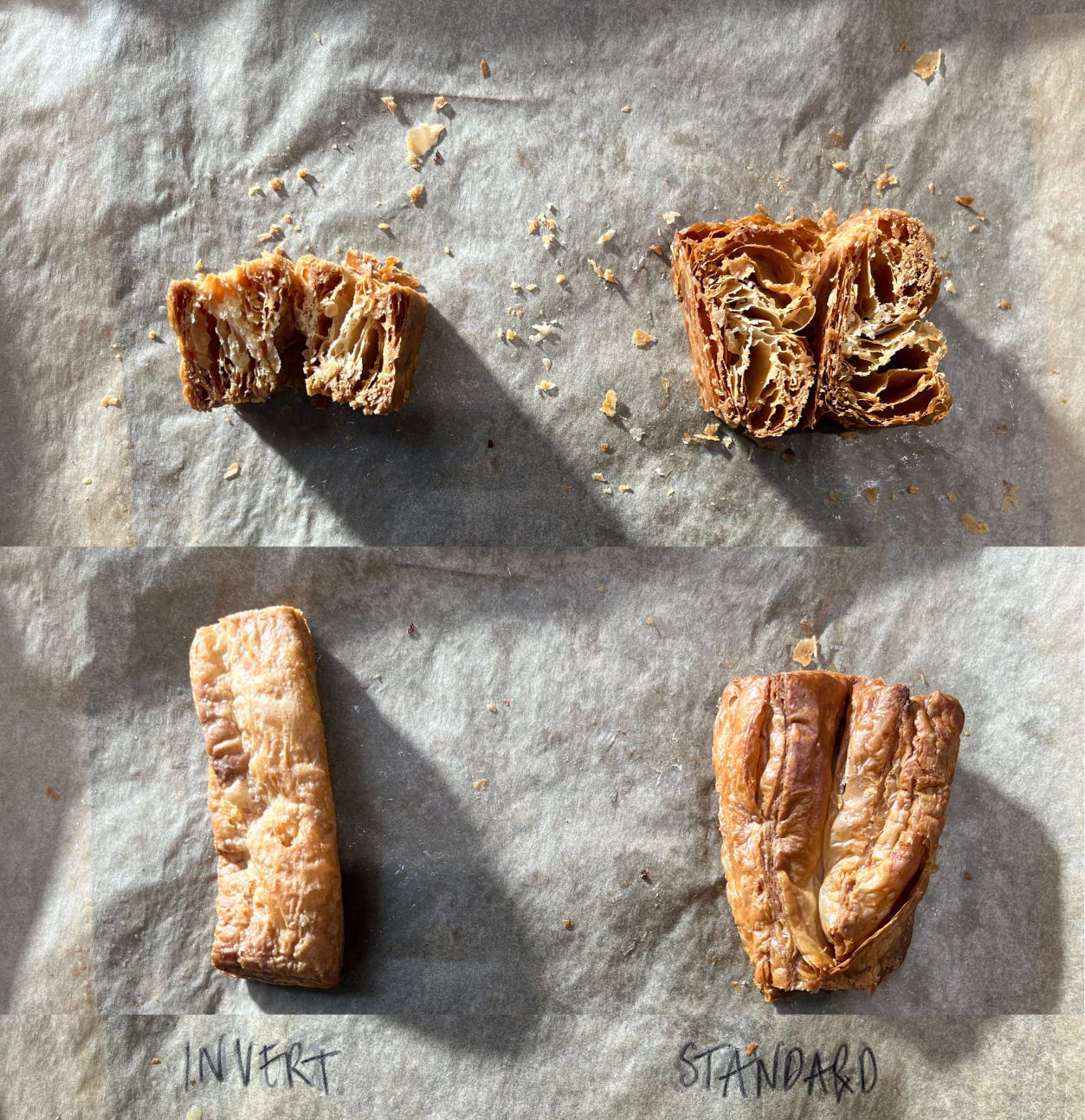

I laminated the two pastries in exactly the same way and then baked. Here’s the results:

Pretty radically different, right? The inverted puff on the left has held its shape and risen very neatly in an organised manner. The classic puff, on the right, went a little crazy. When I ate the pastry side by side, I couldn’t really tell the difference - the inverted puff had a more dense mouthfeel. So, where inverted puff really shines is its ability to hold shape. So, why? Let’s figure it out.

The impact of the butter dough

Remember how in Puff Pastry 101 we talked about how to count layers? Well, that becomes more important when we are talking about invert pastry and understanding the differences.

With regular puff, the layers follow dough / butter / dough, which means that out of 100 layers (for example), the dough / butter will be at a ratio of 2:1 dough to butter. With invert puff, the layers follow a butter / dough / butter ratio, which reverses the ratio ultimately.

When you fold regular puff pastry, each time you fold the pastry, dough will touch dough. This means that the dough layers will be slightly thicker. For invert puff, the butter layer will touch the butter layer, resulting in slightly thicker butter layers. This will contribute to the behaviour of the dough as it bakes, and may be why people tend to think invert pastry is ‘more buttery’.

Although the whole doubled ratio thing sounds really dramatic, this doesn’t actually mean that the invert pastry has double the butter as the two recipes are almost exactly the same proportionally. It does, however, greatly affect how the pastry behaves in the oven, as shown in the post baking pic above. Let’s go deeper

First things first: Gluten

Invert puff has overall LESS gluten: Although the two recipes are exactly the same in quantity, the way that the ingredients are combined is radically different.

Take the rub-in method for example - butter and flour are rubbed together so the fat coats the starch molecules, preventing strong gluten bonds from forming. We are essentially coating the flour in fat as we bulk our ‘butter dough’ which prevents the formation of gluten. As a result, the invert puff has comparably less gluten formation than regular puff.

We love gluten because it allows us to build structure in our bakes. But the downside of gluten strength is its elasticity and memory: Gluten strands can be stretched, but like a rubber band, they will try to return to their original shape. So, when it comes to invert, there is less warping and shrinking due to the relatively fewer gluten bonds - the pastry holds its shape better.

Butter stability

The ‘butter dough’ in inverted pastry is not pure butter - it has been mixed/tempered with flour. By mixing butter with a proportion of flour, we are increasing the range of temperatures that the butter dough is stable. Plain butter which will become greasy and smear very easily, whereas butter tempered with flour can hold its own. Even though the first fold can be *painful*, it is actually much easier to roll out as a result - it isn’t quite so sensitive to temperature changes and is nicely pliable when you’re working with it. In fact, the dough will - counterintuitively - feel firmer and have more integrity.

Also, butter that has been mixed with flour simply does not crack and splinter as easily during lamination due to it being less sensitive to temperature changes. You can also roll the dough more firmly without fear of too-cold butter splurging out. As well as this, you’re more acutely aware of how the butter is feeling. When you are rolling regular puff, it’s harder to be in touch with the butter - it’s sealed in dough, after all - whereas with invert puff, if your butter is getting too warm, you’ll know right away, since the sensory clues are right in front of you. This results in more even lamination meaning a much neater final product.

As well as this, butter that has been tempered with flour has a more controlled rise when it melts. As a result, the pastry rises more evenly. Let’s have a look. When pure butter melts, it splits into milk solids, fat and water. It melts rapidly and quite unevenly:

When butter mixed with flour is melted, it does so evenly and relatively slowly (it takes three times as long as regular butter) and before its all melted, the flour starts frying like a pancake:

When your inverted puff pastry bakes, the butter/flour layer melts in a much more controlled fashion resulting in organised and even layers, rather than the classic puff which expands more quickly and in more random directions.

The deal with hydration

Before we get onto the baking, it’s worth mentioning the importance and role of hydration in the final product. For starters, water is instrumental in creating gluten . This means less water = less opportunities for gluten formation. Secondly, one of the reasons pastry shrinks in the oven is because of the proportion of water present in the dough. When dough goes into the oven, the gluten strands harden and the water evaporates, which can result in a change of shape (or shrinkage). Whilst resting the dough properly in between folds is important, the formulation plays a role too.

Let’s compare the hydration of a standard puff and an invert adjusted puff recipe: A classic puff recipe has overall 22% hydration whilst the invert has just 17% hydration. That is a change of 5%, which is the equivalent difference of almost 25% - pretty significant! This helps explain why our classic puff and inverted puff look so different when baked. The classic puff, to put it bluntly, is wet and wild, whilst the inverted puff is much more controlled.

Baking the puff

For some pastries, we want puff pastry to fly; We want it to glow up rapidly (think GDR, sausage rolls etc.) but for other occasions, it’s lovely to have all the layers without the height. The result is an ultra flaky bite that shatters in your mouth. To achieve this, we need to compress the puff as it bakes. But what gives us the best results?

I tried three methods for baking my puff pastry sheets:

A - Compress pastry with tray

This is the classic method - puff pastry is baked between two identical (if possible) trays to restrict the rise

This is the method we would use in professional kitchens, but I think professional pastry trays are a lot heavier than trays that we have at home!

Results: Lovely, but quite thick because the pastry trays I have at home just aren’t really heavy enough to prevent the layers from lifting. I think this pastry would work as a single layer in a dessert, but for several layers of pastry, I think it could end up being too much

B - Compress pastry with tray plus weights

The classic method but with some extra weight on top! A pyrex filled with baking beans/rice to weigh down the pastry or something like a cast iron could work, too.

This worked quite well but as the pastry was compressed so much that some layers were forced to merge and heat couldn’t properly penetrate, it took a long time to bake. As well as this, there was a lot of excess butter on the tray which had leaked out during baking as it had nowhere to evaporate

The pastry was still good to eat but a bit dense

C - Let pastry rise then compress with heavy tray mid way through baking

Once the pastry has risen for around 10-15 mins, a tray with heavy tray / pyrex filled with baking beans is added on top for the rest of the bake

This technique an attempt mitigate any potential underbaking issues

Resuts - I think this gets you the best of both worlds. The pastry is not overly compressed but it also isn’t too tall and you get a head start on caramelisation

One issue with baking puff pastry, especially when it’s compressed, is underbaking - the layers of pastry can fuse together and a thick layer of undercooked dough - it’s pretty unpleasant to eat so you need to make sure your hold your nerve and bake the pastry for long enough There’s no real going back once its out the oven.

To mitigate this, we’ll pre-heat the oven to 200c (fan) to give it some intense heat as soon as it goes in, then bring the temperature down as soon as it’s in and bake at 180c (fan) until its cooked through, around 45-50 minutes total.

How does regular puff / invert puff compare when baked?

Once baked in the method above - with both compression and caramelisation - there is no discernible difference between regular puff and invert puff. I noticed that, when cutting, the inverted puff held together slightly better (likely due to the less chaotic layer structure), but in terms of flavour or level of caramelisation, there was no difference. Although I’m doing my best to convince you to make your own pastry

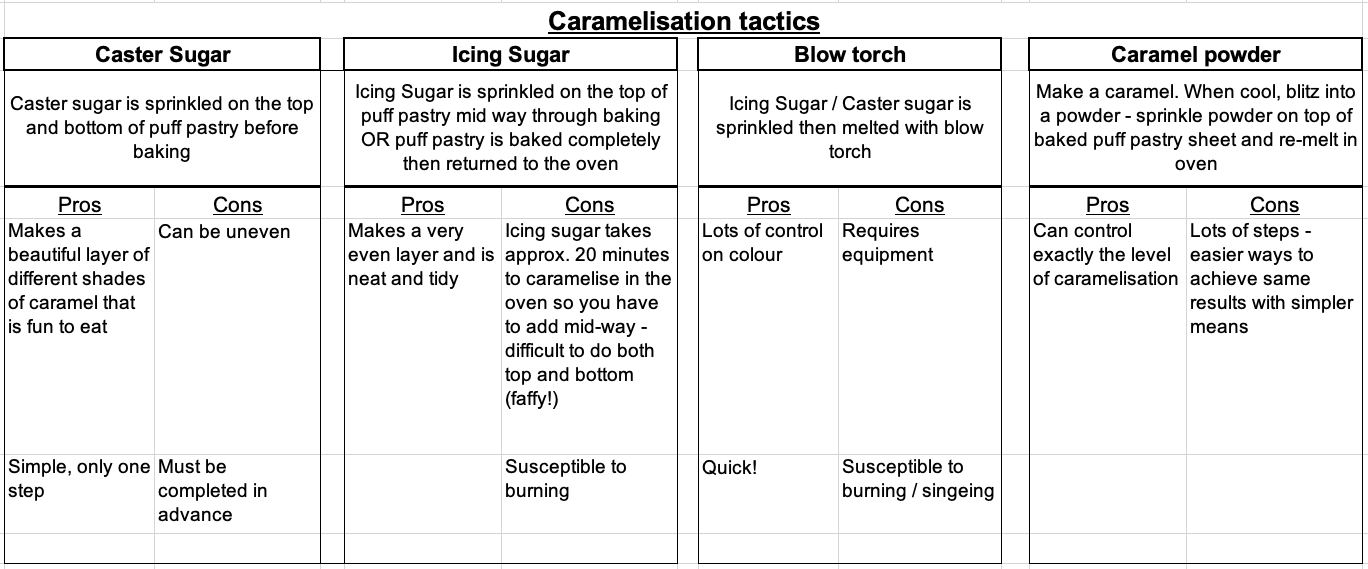

Caramelisation tactics

Puff pastry is already delicious. Puff pastry coated with a layer of caramel? The BEST. There are a few ways to go about caramelising your puff pastry. You can either caramelise it during the bake or after. I tested out all the tactics and here’s the review.

For ease, I’m going to choose caster sugar as my fighter of choice. I love the slightly strange caramel patterns it makes and I love the different levels of caramelisation, it makes it more interesting to eat. If I wanted it perfect, icing sugar is the way to go, but faffing around with hot trays is not something I enjoy doing at home, so caster sugar it is.

One thing to be aware of is the bottom is going to bake much quicker than the top - so you are welcome to flip your pastry half-way through baking, no matter which method you pick - I prefer just to have the base a bit darker than the top, but I guess I’m not a perfectionist.

Another way to lock-in

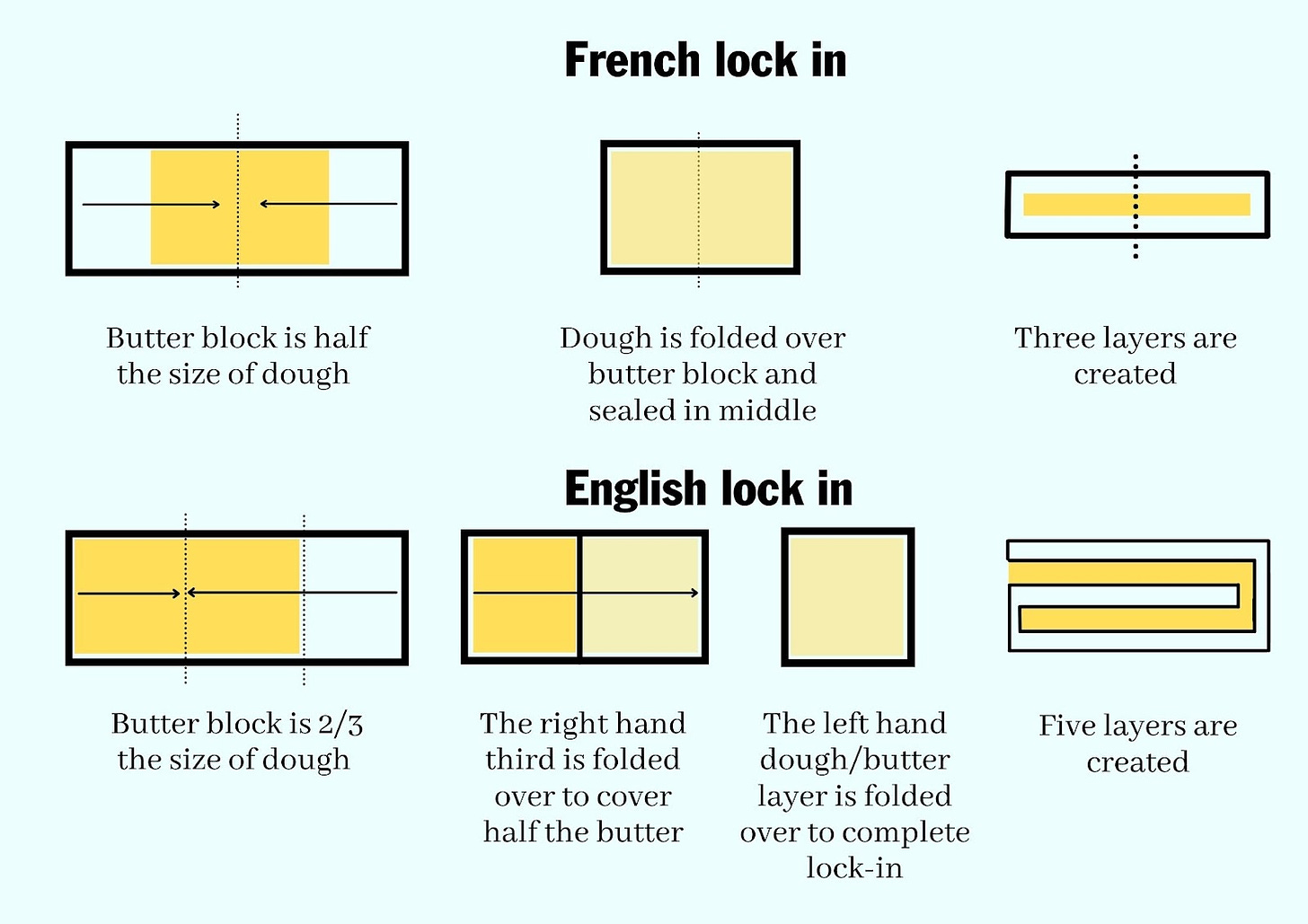

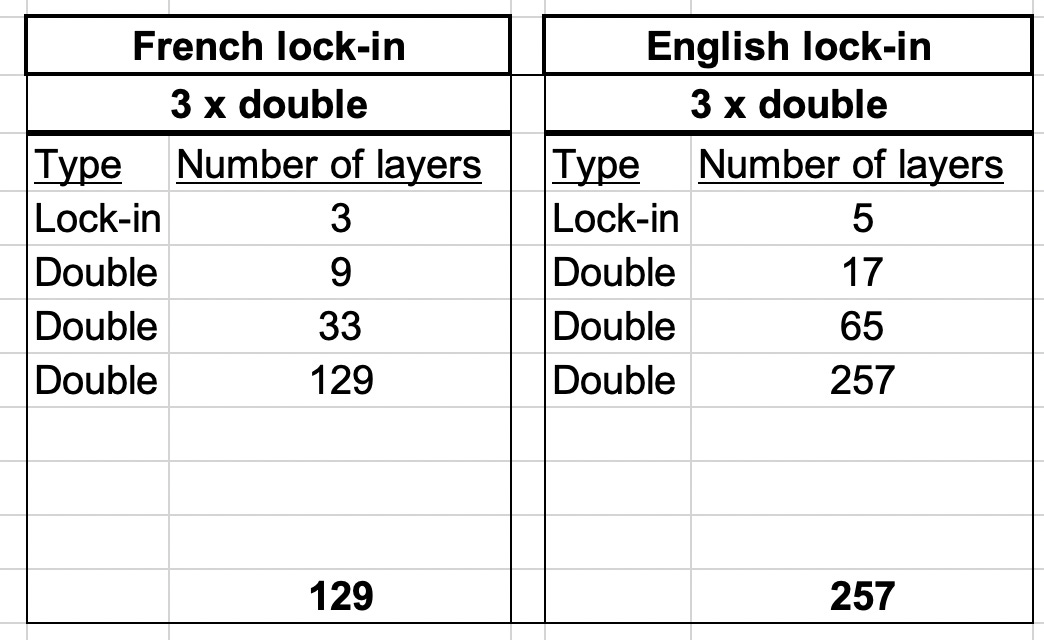

One of the other tricks we have up our laminating sleeves is the way we ‘lock-in’ the butter. The lock-in is important as it establishes the number of layers that make up the foundation of our pastry.

I’ve been shown several ways to lock-in butter during my career, but the two most popular are the French, which we’ve covered, and the English, which I’ll show you today.

French lock-in requires the butter block to be half the length of your dough. Then the edges of the dough are brought together and sealed to create three layers.

English lock-in requires the butter block to be two thirds the length of your dough. Then the butter-less dough is brought half way across the butter. The other half is then folded on top, creating five layers.

Here’s a visual:

This small change actually creates a significant difference on the layers. Let’s have a look at the maths:

So, picking an Engish lock-in is basically a shortcut to extra layers! So, if ultimate flakiness is what you’re after, try an English lock-in next time and get double the layers for the same amount of work.

Alright, let’s make it!

Inverted puff pastry

Makes 500g

100% Butter, very rich pastry which rises less

Detrempe

140g strong bread flour

7g sugar

5g salt

2g vinegar

55g water

60g butter

Butter block

140g butter

60g strong bread flour

80% Butter, still rich but taller and airier

Detrempe

200g strong bread flour

7g sugar

5g salt

2g vinegar

85g water

50g butter

Butter block

160g butter

60g strong bread flour

Method - detrempe - you can also make this in the mixer

Put all of your dries into a bowl and mix

Breadcrumb the soft butter into the dries using your finger tips

Create a well in the middle of your dries and slowly pour in the water bit by bit, mixing with a fork so you are combining the liquid/dries carefully

Once everything is combined, turn onto your work surface squish together until just combined - don’t overwork at this stage

Pat into a approx 15cm x 25cm rectangle and wrap (I like to use a sandwich bag) and rest in the fridge for at least 2 hours

Method - butter block

Mix butter until homogenous then stir through the flour until completely combined

Smear the butter/flour mix onto greaseproof paper and squash into a approx 15cm x 40cm rectangle - use your detrempe to measure it. The detrempe should be 2/3 the size of the butter block

Leave to chill - around 30 mins to an hour is usually sufficient

Method - English lock in

Ensure your detrempe is 2/3rd the size of your butter block. Use your butter block to measure the size

When you are satisfied it is the right size, check the butter block is pliable (if not, roll over a few times with your rolling pin) and then unwrap it, leaving it on its paper. Then stick your dough on top, so it covers 2/3 - you can always fix the size, but its good to go in neatly

Now perform a your english lock in, which is a bit like a single/letter fold: Bring the top third down over the middle, then bring the bottom third up, using the paper to help you. The butter will likely crack and look awful but don’t worry! Just go with it and remember - trust the process

Rotate 90 degrees and roll out the block to 3 times its length - you can do it inbetween paper and use as much flour as you need. Try to keep it in shape

Brush off excess flour and perform a double turn

Chill for at least 1 hour

Perform a double turn, using as much flour as you need - though it should already feel pretty good!

Chill for at least 1 hour

Perform a double turn (also take a moment to marvel at how smooth this pastry feels!)

Your invert is complete! Chill overnight, or at least 2 hours

Method - Bake

Roll your puff pastry out to 2-3mm, taking plenty of rest breaks to get the best shape. Continuously lift your pastry up and off the table to see if it shrinks back. If it shrinks back, the gluten is too fired up. Just put it into the fridge to rest and return 20 minutes later. I measure it against the baking tray to make sure I’m getting the right size

Pre-heat oven to 200c fan

When your puff pastry is the right thickness, sprinkle a tray with 20g caster sugar and place the pastry on top, then sprinkle 30g caster sugar on top

Reduce heat to 180c and bake for 15 minutes - it will probably shrink a bit, but don’t worry. This is normal!

After 15 minutes, place a piece of greaseproof paper on top followed by a heavy tray. I use a standard baking tray with a pyrex filled with baking beans

Bake for an additional 30 minutes

After 30 minutes, check to see if it is baked - you may want to go for another 5-15 minutes / remove the tray if you are struggling to get caramelisation in the centre of the pastry - it should be gleaming and golden!

You can bake your puff up to 2-3 days in advance and keep well wrapped before using for mille feuille, or vanilla slice!

Wanna turn your beautiful puff into a rhubarb & custard mille feuille? Click here for all the deets.

Love puff pastry, especially homemade. Can't wait to try the inverted kind. Haven't had the courage to give it a go yet. 😊

Great Article !

Thank you for going so deep into the process 🤓.

I have a question regarding the folds.

In your process your are making 3 X double after locking. But in your layers counting it’s 1 locking + 4 double. I guess I’ve might missed something about this part. Would you monde to clarify for me.

Thank you !