Kitchen Project #195: Molehill Cake

A peek into a Polish kitchen with Piotr Klosowski

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

Today, I am very excited to introduce you to London-based baker Piotr Klosowski. Piotr and I first met across a shaping table at Little Bread Pedlar in London - we made thousands of croissants together, and bonded over our love of baking. I’m thrilled that Piotr is joining us today for his Kitchen Projects debut to tell us all about Molehill Cake (Kopiec Kreta), the most charming cake featuring chocolate cake, whipped cream, and bananas that is beloved in Poland. I’m obsessed! So cute!

On KP+, Piotr has drawn inspiration from the Molehill Cake and developed a cocoa-crumb-studded banana blondie. Click here to read it!

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc. the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and costs only £6 per month or £50 per year. Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

ps. It’s official… Sobremesa, a culinary retreat in Southern Spain hosted by Milli Taylor at the stunning Rancho del Inglés, is back for 2026! I’ll be baking, teaching and cooking there in May AND August, and I hope to see you there. Find out more on www.ranchoretreat.co.uk. Bookings go live next week!

On Molehill Cake

Poles love their cakes. On discussing the Molehill cake with Nicola, when met with the question ‘What sort of occasion would you make this cake for?’, I was slightly taken aback, needing a moment to think about my answer. After all, a cake doesn’t need an occasion!

Of course, there are the beautifully decorated, multi-layered cakes with syrup-spiked, lighter-than-air sponges and playfully coloured creams reserved for special occasions such as birthdays, weddings, christenings, or other milestones. All other cakes are simply for eating, at any time - it is the cake that makes it an occasion. It might be a little treat with your 11 am coffee (turns out my parents, who have never been to England, have adopted the tradition of ‘elevenses’), or perhaps a friend makes a spontaneous visit - a sentence that not only shows my age, but also how small-town-esque the small town where I was raised is. It was considered quite impolite not to have a cake ready for guests.

When I was a kid, the most important day of the week was Sunday. At 11 am, there was a family visit to church for mass. The highlight of the day was walking home afterwards via our town’s only patisserie; the big brown letters ‘CUKIERNIA’ on the side of a grey-ish building have always caused a Pavlovian reaction (though hardly ever from pavlova) of excitement in anticipation of an imminent sugar rush.

The queue was usually long, which turned out to be an advantage, offering an opportunity to thoroughly browse the pastry case and choose the “one thing” I was allowed to get. The choice was always overwhelming - eclairs, sliced and piped full of vanilla (flavouring) crème pâtissière and chocolate glaze, jam doughnuts (pączki) and cream cheese doughnut holes dusted with icing sugar (pączki serowe), enticing brown-crusted, deep fried crullers with gloriously sickly sweet glaze (gniazda), an array of roulades, sheet cakes sold by the kilo, shortcrust tartlets with cream and fruit, cavity-inducing meringue-filled profiteroles and multiple types of cheesecake (sernik), with or without raisins, some latticed, or adorned with almond flakes and fried candied peel. But one thing you’d never find in a patisserie is a Molehill Cake (kopiec kreta). That was very much a treat reserved for making at home.

on KP+ today: Cocoa Crumble Banana Blondies

Inspired by Molehill Cake, Piotr has developed a cocoa crumble banana blondie, full of mix-ins with gooey-terrazo energy.

What exactly is Molehill cake?

My family home didn’t have many cookbooks. There were a few Reader’s Digest issues on healthy eating and a couple of books on traditional Polish cuisine. Like most families, we had “zeszyt”, a battered school exercise book filled with all sorts of recipes: cut-outs from newspapers and magazines, recipe ideas cut from the backs of packaging, handwritten notes from neighbours, friends or family. However, the subject of this article, Molehill cake (kopiec kreta), is not one of those recipes. In fact, the history of this cake is about as unromantic/prosaic as it gets.

It was introduced to the world as a boxed cake mix produced by Dr Oetker, the German company best known for its baking powder (and other baking ingredients and decorations), cake mixes, and frozen pizzas. It first hit the shelves in Germany in 1999 under the name Maulwurfkuchen as part of a product line called “Trend Backmischungen” (Trendy baking mixes). In 2002, it made its debut in Polish supermarkets alongside two other cakes with equally creative names: ‘Kilimanjaro’ (Molehill’s close sibling, which replaced bananas with tinned peaches) and ‘Blue Lagoon’ (an unhinged cousin with blue jelly, chocolate palms and dolphins).

In the most basic terms, Molehill cake is a chocolate sponge with its top sliced off, filled with sliced bananas, whipped cream and chocolate chips. The top of the cake is crumbled over the cream to resemble a molehill.

Molehill cake quickly became a popular staple in homes across the country. Twenty-three years later, and the boxed Molehill cake mix is still available in Polish supermarkets - including those here in the UK. It has since been adapted into many, many versions, including black cocoa, cheesecake, summer berries, or, the most outrageous/hilarious addition, a Shrek mound.

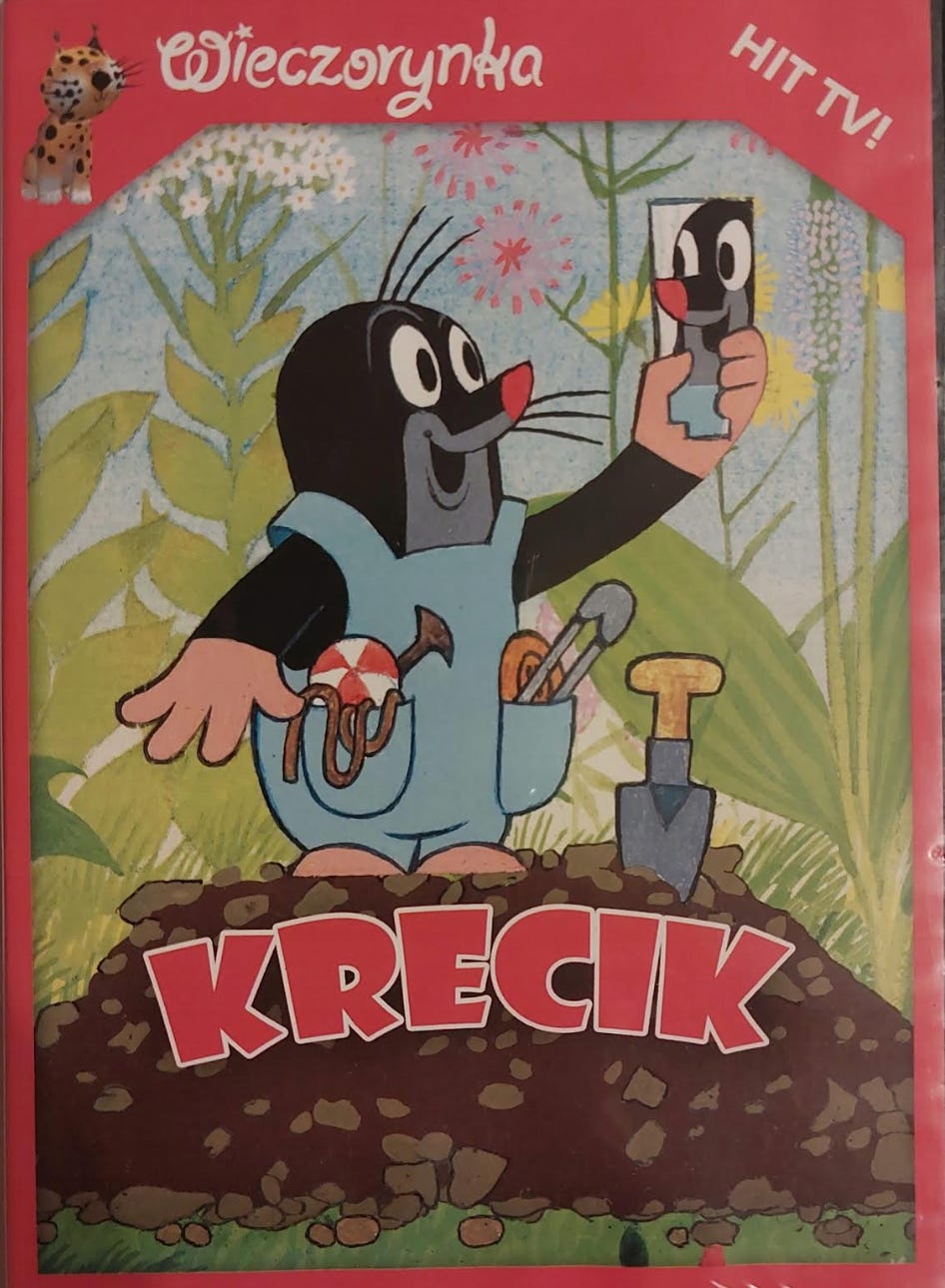

So what is it about Molehill cake that made it so successful, particularly in Poland? For one thing, compared with most Brits, Polish people have a positive view of moles. Rather than seeing them as garden-wrecking invaders, we Poles have an image of a happy and resourceful little fellow with a red nose, wearing blue dungarees. That’s all down to an old Czech cartoon called The Little Mole (Czech: Krtek, Polish: Krecik) created by Zdeněk Miler in 1956. Generations of Poles grew up watching this little mole and his comic adventures; our perception of this little creature changed forever, and seeing a mound of soil generally carries a positive association (apart from avid gardeners).

Another reason for the cake’s success lies in its simplicity and the high reward-to-effort ratio. Somewhere during the assembly of this cake, the magic happens, and the finished product tastes greater than the sum of its ingredients.

Making a mountain out of a molehill

I’m not exactly sure whether it’s boredom or curiosity that drives me to constantly tweak a recipe. Baking and pastry tend to attract certain types of people - often artists and perfectionists, both of these groups are well known for never being satisfied with the outcome of their labours. Professionals often go to great lengths, tweaking a recipe, looking for minuscule differences that may not be perceptible to the average consumer, especially when there is no control sample for comparison. Is complicating a cake really worth it? Can minuscule differences combine to create one big tasty difference in the end product? Perhaps, but in the case of our molehill cake, do refinements add to the experience or detract from its homely charm?

The Cake

The base of the Molehill cake is a chocolate sponge made employing the ‘muffin’ method. Unlike the creaming method, which aerates the fat and sugar before adding the dry and liquid ingredients, the muffin method combines the dry and wet ingredients in separate bowls, then mixes them swiftly to avoid gluten development. The result is a tender, ultra-moist, fluffy sponge. The best-known chocolate sponges made with this method are Devil’s Food cake and Guinness cake.

During my time at Giddy Grocer, an independent greengrocer in Bermondsey that champions British produce, I used to riff on a Guinness cake, using locally brewed stout from one of the many artisan producers on Bermondsey’s Beer Mile. The cake was one of our bestsellers, and there was never a week I wouldn’t be whipping up a batch.

For almost two years, new changes were constantly introduced - some out of necessity, like using regular yoghurt in place of Greek or using a different beer. Some changes made sense from a taste perspective, such as adding a portion of dark brown sugar, coffee powder, or vanilla powder (spent vanilla pods were left to dry out and then blitzed in a spice grinder for a small flavour contribution in cookies and cakes). Unfortunately, it is hard to see the difference in flavour without a control sample, so I never really knew if the changes were worth my time. Until now!

The tests

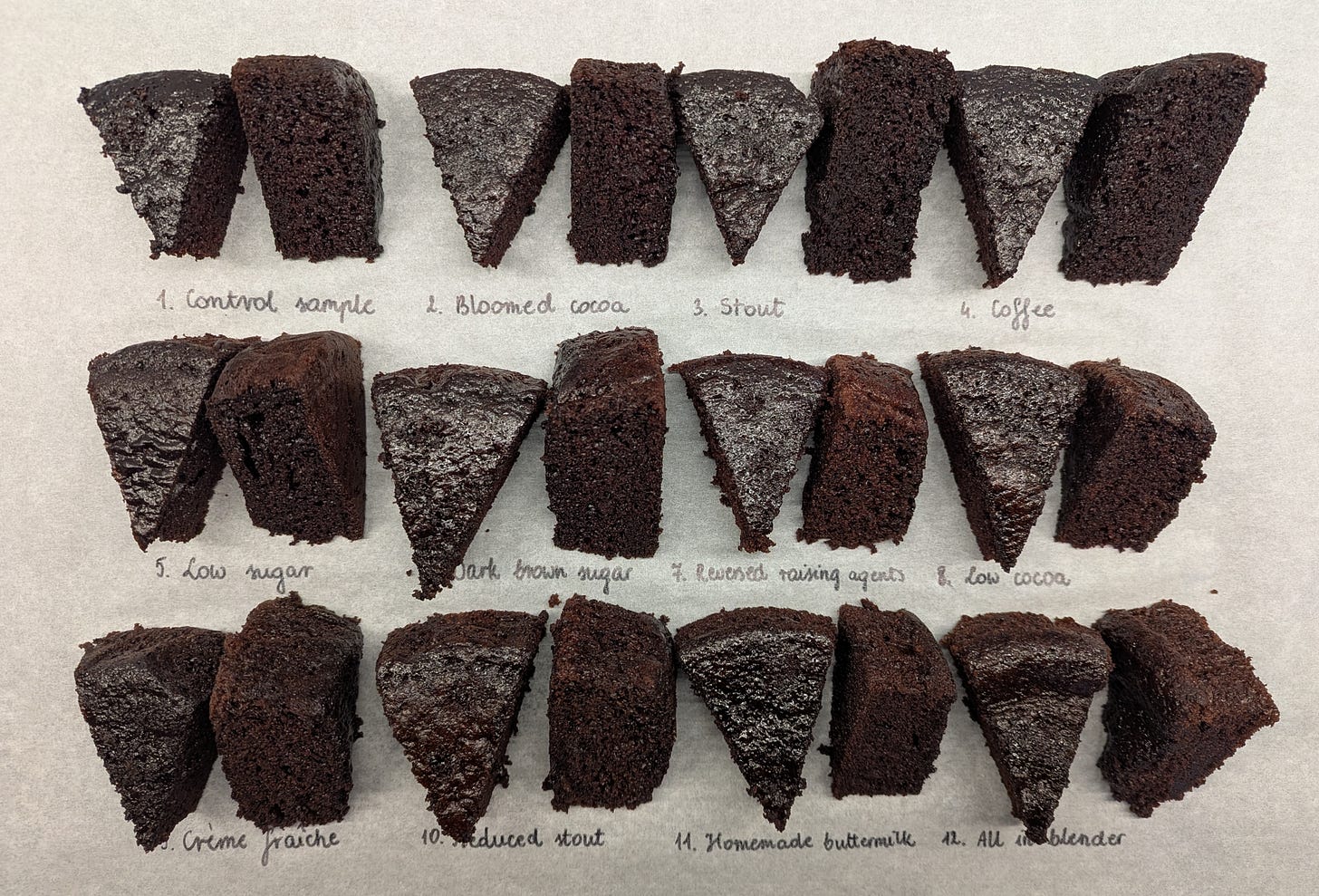

I began by making 12 different versions of the base recipe, each cake with only one variant changed. Here are my findings:

Control sample: made using my staple recipe- full of cocoa, sugar and lots of yoghurt and boiling water to keep it nicely moist. It has a very open, springy crumb and a definite/pronounced cocoa flavour.

Bloomed cocoa powder: For this cake, I combined cocoa powder with hot liquid to release flavour compounds and achieve a deeper chocolate flavour. The base recipe contains a good amount of liquid, which is heated up before being added to other ingredients, so it’s an easy enough step to add. Surprisingly, the resulting cake had a slightly dimmer, yet a bit more rounded cocoa flavour.

Verdict: The difference was so minimal that I wouldn’t bother with it again.

“Thin” liquid - coffee/ stout/ reduced stout (3, 4 and 10.): When making this cake for the Giddy Grocer, I would generally use a local beer to add a depth of flavour and maltiness. However, given the high proportions of cocoa and sugar, I wondered how noticeable the difference really is, especially since a can of beer might be the most expensive ingredient on the list.

Verdict: Good news! Adding stout definitely changes the flavour, even though without a control sample, it would probably be harder to pinpoint the difference. Using coffee was equally noticeable and pleasant. Bad news- in the process of boiling and reducing stout, a lot of the beer’s flavour compounds disappear, the resulting cake was extra sticky, almost doughy, but lacking any extra flavour.

Amount and type of sugar (5 and 6): Most recipes for muffin-method chocolate cake call for a high sugar-to-flour ratio, often balanced with copious amounts of cocoa, coffee, and beer. High sugar content increases moisture and improves the cake’s tenderness, and even though it is not a noticeably sweet bake, I wondered how critical the amount of sugar is.

Verdict: It turns out that a cake with 33% less sugar was very bland, leaving the cocoa flavour noticeably muted. The version with all dark brown sugar had a nice aftertaste, but the texture was more pasty/ doughy, definitely not worth an extra step.

Ratios of raising agents: This one I was most curious about. I’m always cautious about using baking soda to its fullest potential, afraid the cakes will taste soapy because my formulations aren’t acidic enough to fully react with the bicarb.

Verdict: Swapping the baking powder-to-bicarb ratio produced a cake that was crumbly and tasted a tad bland. I recommend sticking to the original ratio.Amount of cocoa: The base recipe calls for a generous amount of cocoa. I wondered whether it was too much of it, and a smaller amount might be sufficient.

Verdict: A cake made with 25% less cocoa still tasted rich and smooth, but the flavour was slightly muted. Next time you’re missing 5 or 10 grams, save yourself a trip to the shops and make the cake anyway!“Thick” liquid - crème fraîche/homemade buttermilk (9 & 11): The recipe I originally based my cake on used buttermilk; however, for convenience, I replaced it with yoghurt. I read The Pancake Princess’s ‘Guinness Chocolate bake off’ in which she mentions that cakes using sour cream were rated better than those using buttermilk. In my trials, I adjusted for extra fat to determine whether that was the only factor driving the difference. I also tried a homemade buttermilk substitute as a budget-friendly alternative.

Verdict: The version with creme fraiche definitely delivered on flavour- the cake tasted more of chocolate rather than cocoa. Texture was less fortunate; one of the words my tasters and I agreed on was “gluey”. Homemade buttermilk (milk + vinegar) provides a nice texture and a subtle change in flavour compared to the control sample; it's definitely an option to consider.12: All in blender: I wanted to see whether there is a way of simplifying this recipe even further, by putting all the ingredients into the blender at once - unfortunately, this test was a total failure in terms of texture- dense and unpleasantly chewy. I guess it is best to stick to a simple whisk! (Say goodbye to the idea of making this cake directly in a baking pan.)

The Results

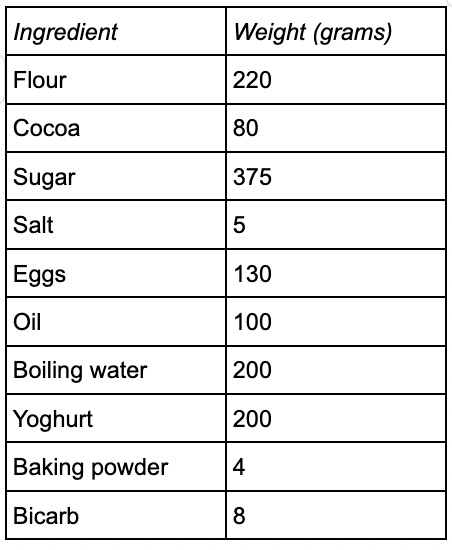

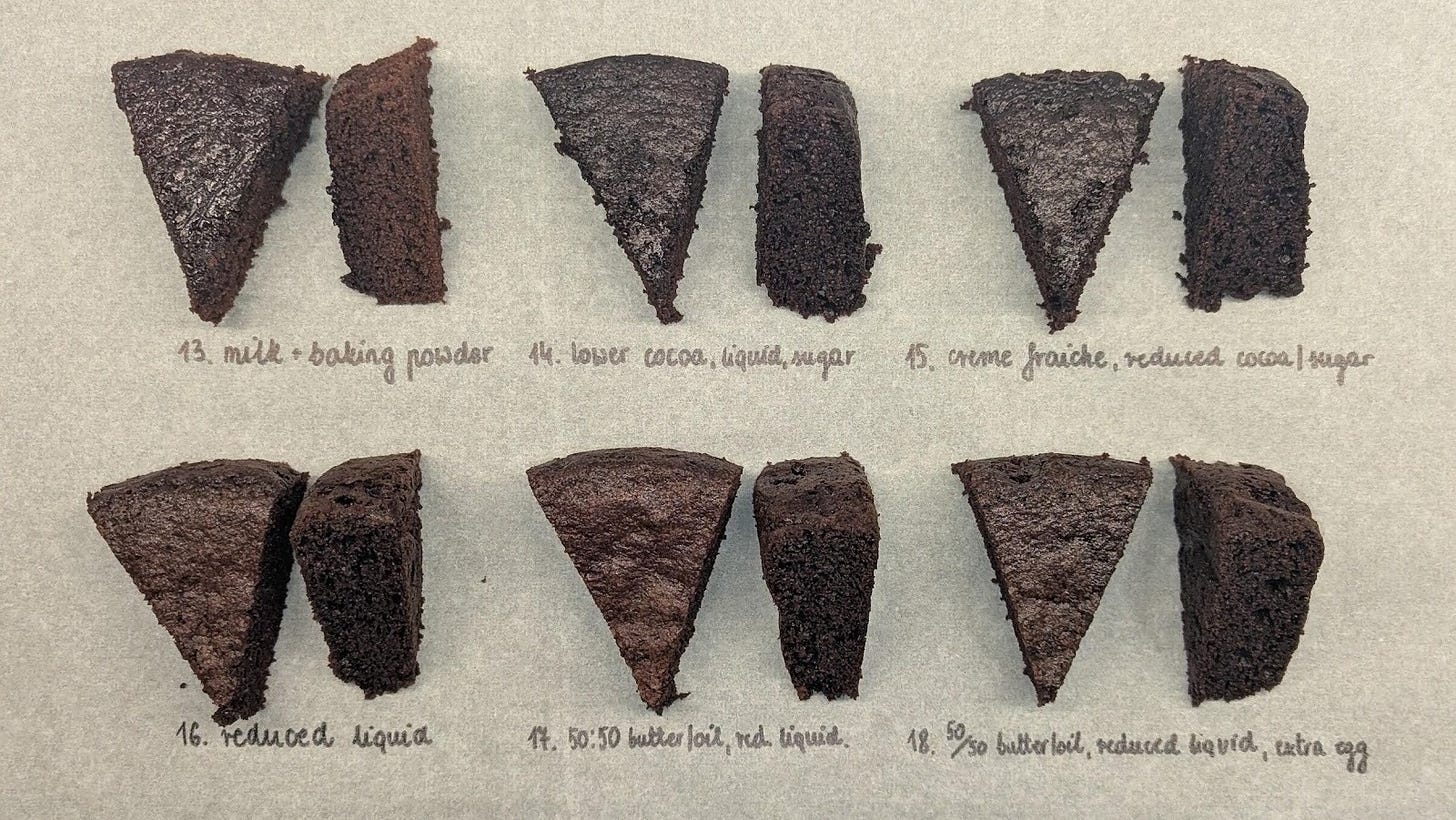

After these 12 trials and accounting for all the noted differences, it was time to consider this cake holistically. To make crumbs from the top of the cake to form our molehill, the base needed to be a fraction drier and more structured. Inspired by the promising texture of the cake made with homemade buttermilk, I tried replacing yoghurt with milk and using baking powder instead of bicarb. The resulting cake was drier, with a crumb that was too tight and not well risen. Another trial to lower multiple ingredients that affect structure- cocoa, liquid (goodbye stout!) and sugar also proved unsuccessful, delivering a less satisfying flavour.

My efforts to simply reduce the liquid resulted in a drier sponge, but with a less pronounced cocoa flavour. To rectify this, I tried replacing some of the oil with butter, which left the cake slightly sunken in the middle but had a good flavour. For the last trial, I added an extra egg to prevent the dent. The result is an evenly baked light sponge that is deliciously chocolatey and dry enough to crumb well (rather than turn into a paste).

The Bananas

A key component in the Molehill cake is sliced bananas. This sounded very unimaginative, so I set myself the challenge of elevating it. The cake’s flavour profile- chocolate, cream and bananas-is similar to Banoffee pie, created in the 70s by Ian Dowding at the Hungry Monk restaurant in Sussex. This iconic creation consists of a pastry shell filled with condensed milk caramel (dulce de leche) and bananas, topped with whipped cream and chocolate shavings. This gave me a clear vision- caramel was the way to go- so I set out to test ways of incorporating it into the recipe. Trials included:

Bananas fried in a pan with brown sugar and butter (Bananas Foster style),

Dry caramel de-glazed with mashed bananas to create a banana caramel sauce,

Bananas mashed and cooked out with dark brown sugar,

Caramel sauce (with butter and double cream) cooked with chopped bananas.

The first test had a really deep, concentrated banana flavour, the texture was unforgivable- soft and slightly slimy. Second try - banana caramel sauce was promising, but the bananas highlighted the wrong parts of the caramel; it was oddly fruity and bitter. The third trial was also disappointing; although it delivered on flavour, it had an unappealing colour and texture. Finally, making a caramel sauce and cooking bananas in it delivered in all categories- flavour, texture and appearance.

Later, I assembled a molehill cake with a banana-caramel filling and fresh bananas for added texture. Trying the new creation as a whole was a little bit disappointing. Punchy caramel flavours threw this cake off balance, stealing attention from the other components. The new addition also seemed at odds with this cake’s core premise - uncomplicated, comforting, easy to make. I whipped up another cake with sliced bananas and instantly realised that sometimes the simplest answer is the right one.

Of course, if bananas are not your thing, you could use other fruits. I think most soft fruits would make a great substitution, or for another 70s throwback, why not use lightly cooked syrupy cherries for a Black Forest-inspired molehill?

Cream

The final element of the Molehill cake is whipped cream with chocolate flakes. Having lived in England for the past decade, I’m very familiar and appreciative of double cream. Its extra high fat content is a great insurance policy when used in layer cakes. However, I wanted to stay closer to the original. In Poland, double cream doesn’t exist, and most whipping cream contains just 30%-36% fat. This less stable cousin of double cream is sold in the UK as “whipping cream”. What it lacks in stability, it definitely makes up for in texture- a lot lighter and airier, a dream! You can decide which you prefer - a lighter, airier version (go for whipping cream) or a more stable one (double cream)

The original Molehill cake box mix includes a packet of chocolate flakes to be folded into the whipped cream. The flakes are about halfway between chocolate chips and shavings. I find that either finely chopped or coarsely grated chocolate makes a great substitute. My recommendation is to use a chocolate that is neither too sweet nor too robust - 55-60% cocoa solids work well here, but feel free to use whatever you prefer.

How to adapt the Molehill Cake

Plain cream is a welcoming canvas for all additions and infusions. Introducing complementary flavour is a great way to add your personal touch and make the recipe “yours”. Why not try vanilla extract or a grating of tonka bean or nutmeg? If you like something bolder, try adding barley malt (5-10% of the cream’s weight will make it taste like a delicious cup of Ovaltine/Horlicks). If you want to give it a try, use about 60g of hazelnuts per 300 ml of cream. Lightly smash the hazelnuts, then toast them over low heat, then add the cream and bring to about 70 °C. Let cool to room temp, then refrigerate for at least 4 hours, or better, overnight, before straining and using in the recipe.

RECIPE: Molehill cake

Makes 1x 8-inch round cake, serves 8-10

Chocolate sponge:

110g Plain flour

40g Cocoa powder

2g Baking powder (about ⅓ - ½ tsp)

2g Bicarb

180g Caster sugar

2g Salt

75g Eggs (around 1.5 eggs))

35g Neutral oil, like vegetable oil

40g Unsalted butter- melted

55g Yoghurt

Filling

300g Double cream or Whipping Cream

30g Icing sugar

45g chocolate (min. 50% cocoa solids)

200g-250g bananas (around 2 medium bananas)

Method

For the sponge, pre-heat the oven to 160°C fan and line an 8-inch round cake tin with parchment paper.

Sift flour, cocoa powder, raising agents, caster sugar and salt into a bowl, then stir the dry ingredients using a whisk to evenly distribute the components.

In a separate bowl, whisk together melted butter and oil, followed by yoghurt and eggs.

Add dry ingredients to the wet mixture and mix until combined. Scrape the thick batter into the prepared tin and level with a spatula.

Bake for 30-35 minutes or until the centre of the cake springs back when touched. Leave to cool.

For the filling, finely chop or grate the chocolate and set aside.

To assemble, place the cake onto a serving plate. Form a well using a spoon to scoop out the inside of the cake (around 1.5-2cm deep), leaving a 1cm border around the circumference. Transfer the scooped out crumbs into a bowl and set aside. Create a rough texture to the outer wall of the cake using a fork or serrated knife.

For the fillings, slice the bananas into 0.5cm thick coins and set aside.

In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a whisk attachment (or a regular bowl if using a handheld mixer or whisking by hand), add the cream and sift in the icing sugar. Whisk the cream until it forms stiff peaks, then fold in the chopped/grated chocolate and set aside.

Arrange the sliced bananas over the base of the well, then layer the cream on top. Smooth it out with a palette knife (or a butter knife) to form a dome.

Cover the cream with cake crumbs (process a little with your finger tips if they are too big), gently pressing them into the cream.

Place the cake in the fridge for at least a couple of hours to set (keeping the cake covered in the fridge overnight will make it easier to slice) before slicing. Store leftovers in the fridge, covered, for several days.

Thank you for this great bit of Central European nostalgia!