Kitchen Project #163: Sussex Pond Pudding

Is this oldie still a goodie? An exploration by Camilla Wynne

Hello, and welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects.

I have been SO excited to share today’s edition of the newsletter with you. Camilla Wynne is taking us on a ride through dessert history with this deep dive (appropriate) into Sussex Pond Pudding.

Never heard of it? Well strap in, because it’s a real journey. Over on KP+, Camilla is sharing another peak citrus dessert - a Double Rye Lemon Shaker Pie. Definitely one for the lemon lovers. Click here for the recipe.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the writers), join a growing community, access extra content (inc., the entire archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £6 per month or £50 for the whole year. Why not give it a go? Come and join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

What on earth is Sussex Pond Pudding?

by

If you’ve never had the privilege of trying Sussex Pond Pudding, imagine, if you will, an obscene amount of butter and sugar tucked inside a suet crust. At the very center? A whole entire lemon. Steamed for 4 hours, the pudding emerges a burnished golden brown, shaped rather like a tall bowl set on its head. The pastry is soft, but sturdy, and the lemon is tender - a little chewy and sugar-saturated-- like marmalade. Upon serving it disgorges a great pool of lemon-scented toffee sauce that earned it its name.

Laurie Colwin, one of the great food writers of the last century, wrote about Sussex Pond Pudding in the chapter of her book titled Kitchen Horrors—but not because she didn’t like it. “My greatest [kitchen] horror was a culinary triumph, in my opinion. In my opinion are the crucial words… Suffolk [Sussex] Pond Pudding, although something of a curiosity, sounded perfectly splendid… It never occurred to me that nobody might want to eat it.” Her guests told her it looked like both a baked hat and the Alien, and that it tasted like lemon-flavored bacon fat. Colwin devoured it herself nonetheless, while her undistinguished guests had ice cream.

What I’m trying to say is that Sussex Pond Pudding might not be for everyone. Gird your loins. Adjust your expectations.

It should perhaps have been a red flag when lauded recipe developer Nicola Lamb assigned me this topic after striking out herself. But she doesn’t like mincemeat or Christmas pudding either, so I chalked it up to her British culinary blind spots. And I admit that I am rather known for enjoying flavours to which many others object—marmalade, liquorice, fruitcake and durian, to name a few. Sussex Pond Pudding has been around for hundreds of years. I felt sure I could see what’s to love.

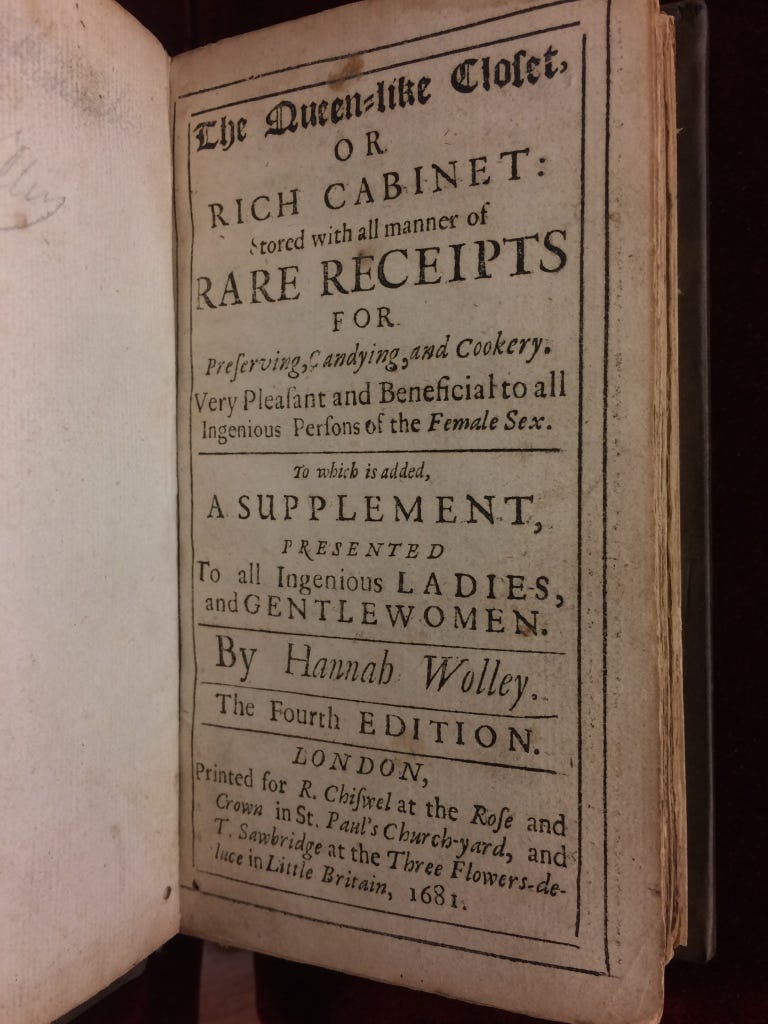

A Very Old Pudding

If you put me in a time machine and sent me to the 17th century, however, I’m not convinced I could be seduced by the original recipe. Sussex Pond Pudding is related to the unsweetened sponge puddings served in place of bread to accompany meat. According to Regula Ysewijn, author of Pride and Pudding, the oldest recipe for it appears in 1672 in Hannah Wolley’s The Queen-like Closet, though it was filled with apples or gooseberries rather than a whole lemon and garnished with barberries. One might mistake it for Kentish Well Pudding, seeing as they’re basically the same—no surprise since Sussex and Kent are neighbors. In the Kent version, however, a handful of dried currants takes the place of the lemon. The lemon doesn’t actually appear in a published recipe until the 1970s in Jane Grigson’s English Food, although it doesn’t seem to have been her invention and is reported by some to have been customary since at least the 1950s.

Grigson called Sussex Pond Pudding “the best of all English boiled suet puddings,” while Delia Smith laments it as “one of the truly great English puddings, which has, sadly, fallen victim to the health lobby.” Even in the 18th century, however, some were complaining about the intense richness of the dish, Sussex shopkeeper and diarist Thomas Turner disapprovingly calling it “butter pond pudding.”

To Suet.. Or Not to Suet?

Sussex Pond falls under the umbrella of sweet suet puddings, alongside Spotted Dick, Jam Roly-Poly, Clootie Dumpling and, of course, Christmas pudding. Suet puddings became common in the 17th century when pudding-cloth was invented, making it possible to steam or boil large puddings (rather than cooking them in animal organs or skins). They reached the height of their popularity during the Victorian era—George I was also known as Pudding George! From there, however, their popularity began to wane.

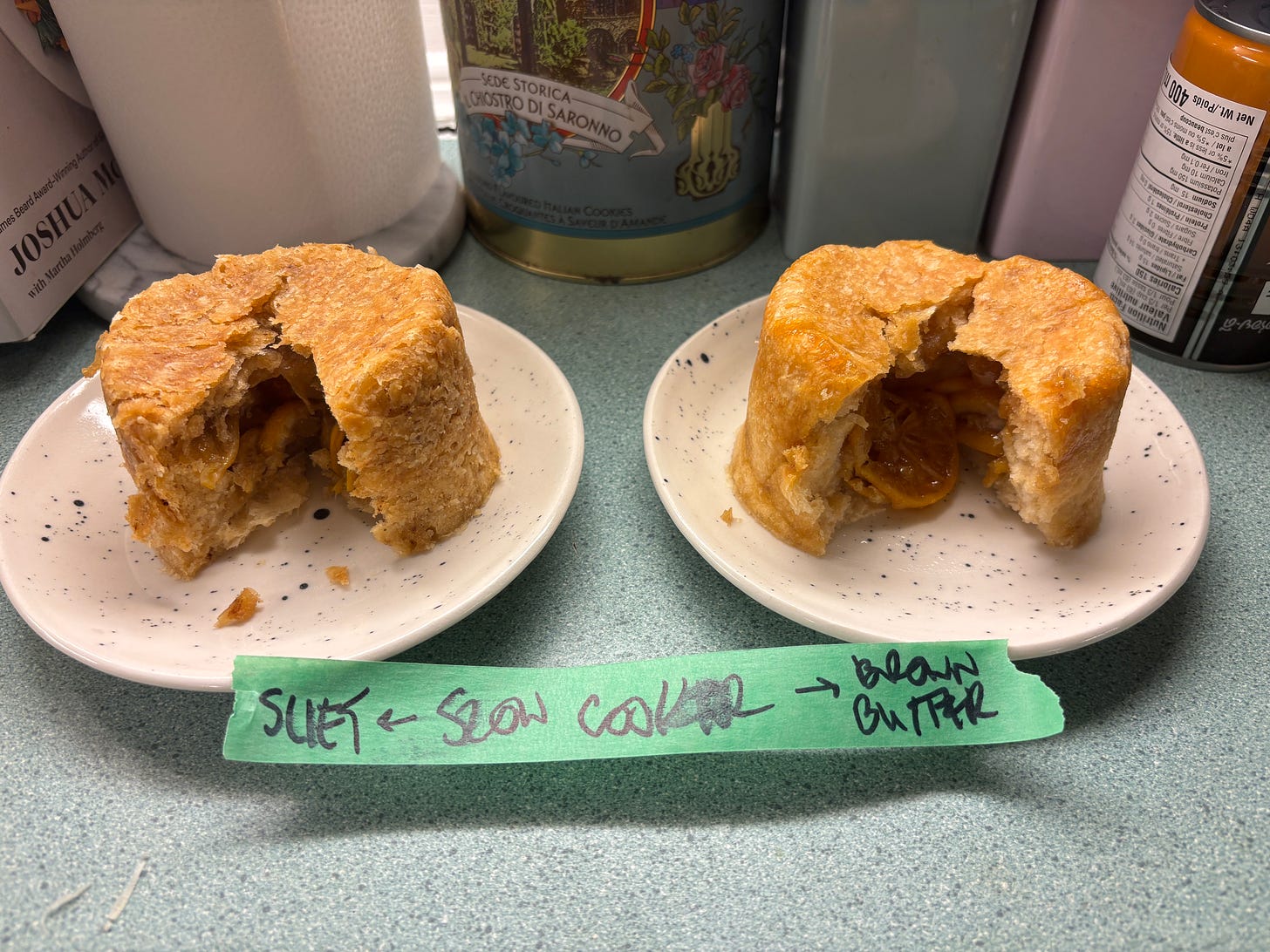

Suet’s high melting point makes for a pastry with a lightness you can’t achieve with other fats. Unfortunately, it’s not vegetarian, being the hard fat from around beef and lamb kidneys. Nor is it easy to find outside of the UK—here in Toronto I got hold of a single carton of frozen beef suet no doubt leftover from a special holiday order. I don’t expect to see it for sale again until next November. Of course, your local butcher might oblige, but having once cleaned a mass of suet of its blood-tinged membranes to make old-fashioned mincemeat, I can assure you I won’t be repeating the task.

In the UK, suet is so embedded in the cuisine that they even make a vegetarian version, but I’ve never gotten my hands on any to try. Instead, I used the same trick I do in my mincemeat, subbing in cold, grated brown butter, which has the benefit of a lower water content as well as some more depth of flavor. You won’t, of course, get that flavor that Colwin’s guest described as “lemon-flavored bacon fat” (which I think is off the mark anyway), but it does make for a nice pastry that handles about as well and almost achieves the same deep shade of burnished brown.

If you can find suet and aren’t vegetarian, I do recommend trying it, as long as it’s good quality fresh or frozen suet. (If Nigel Slater won’t bother with the shelf stable stuff at the shop then neither would I.) Certainly the flavour isn’t for everyone, but I like its unique, ever-so-slight beefiness. Someone once commented that it tastes like proper chips!

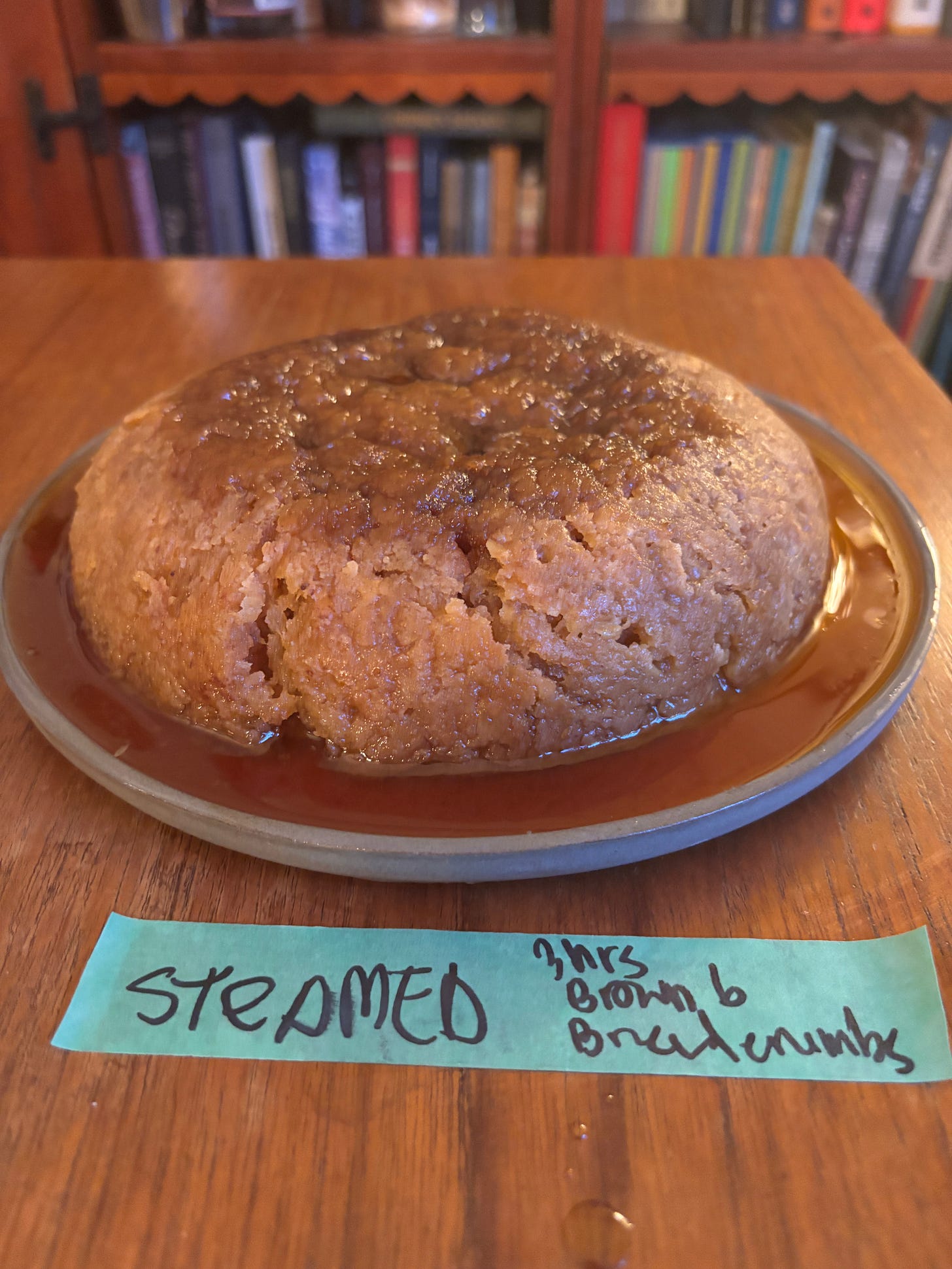

Hydration

Nearly every recipe you’ll find for suet crust uses roughly the same 2:1 ratio for flour to fat. Some use breadcrumbs in place of some flour, which likely started as a way to use them up but is supposed to create a lighter crust, since they don’t develop gluten. In the one test in which I employed them I didn’t see much difference. The baking powder I was employing was already contributing lightness, an addition probably made just after its invention in 1843 (though I found I had to reduce the initial 2 tsp I employed, as the dough puffing up prodigiously can blow off the top and squeeze out the filling.) I also added a little sugar to my dough to help get a more attractive burnished colour. Perhaps because I didn’t grow up with steamed puddings, I find a really pale one somewhat repulsive.

Test after test, however, I struggled to get the eponymous pond. It seemed the dough was just absorbing all the melted butter and sugar. Nice to some degree, that saturated pastry, but lacking the big reveal that seems to be the main attraction of the pudding. When I finally got my hands on Jane Grigson’s original recipe from English Food, I was surprised to find how much liquid she used in the pastry—65% more than what I’d been using. Her instruction was that the dough be very soft, just not too soft to roll. I’d been foolishly making a sturdy pastry with low hydration, eager to suck up all that toffee sauce. It made sense to me that a softer dough might better withstand the advances of the melting filling, leaving it to pour forth when cut.

Filling

As a pastry person, I don’t think of myself as ever being squeamish about large quantities of butter and sugar—that’s basically what I’m made of. However, there was something about just cramming a pastry case full of diced butter and sugar that made me just a little skittish. This is a recipe where the gloves come off. There are no niceties. It’s fat and it’s sugar and that’s the joy of it. But I had to learn the hard way. Balking at the amount of butter and sugar, I dialed it back but ultimately found that if you want a pond, as well as to balance the bitterness of the lemon and the unsweetened crust, you need a great deal - I had reduced the sugar by 100 g compared to other same size recipes and ended up adding half of it back.

As far as the lemon is concerned, it’s non-negotiable. But don’t take my word for it—Jane Grigson said “the genius of the pudding is the lemon.” All that fat and sugar requires the bracing balance of citrus. Reading that it should be thin-skinned lemon (though given the ever changing anatomy of citrus over time, what might have been a ‘thin-skinned’ lemon once, might be an average lemon now), I began my tests using Meyers, the only reliably thin-skinned variety available to me. I was unsatisfied. Fortunately, my laziness got the better of me and I didn’t want to go to the specialty store again once I ran out of Meyers, so I tried a regular old Eureka lemon—and much preferred it! Meyers are a cross between a lemon and a mandarin, so are sweeter than the average lemon. I say the sourer the lemon the better to accomplish the job of balance, which also goes for the bitterness of the thicker skin. Even a thick skin succumbs to tenderness after 4 hours of steaming.

In the original recipe, the lemon is pricked all over with a larding needle (a long metal spike meant for kind of sewing lardons into raw roasts to baste them internally. A modern wooden skewer does the job!) so as to allow the juices to escape—and to prevent the lemon from exploding. A non-pricked lemon yields a pudding known as Lemon Bomb. While I love the drama of the whole lemon (short of it causing an explosion), the realities of serving the thing cause some difficulty.

Some choose to thinly slice the lemon, but I wanted something more akin to the big chunks of lemon you’d get from the original, without having to wrestle with a thick skin and a serving spoon. I top and tail my fruit, cut it into eighths lengthwise, remove the seeds, then cut the eights into four chunks or so to make 1-inch pieces.

It occurred to me as well that marmalade might pose a handy shortcut. I only had Seville on hand, but subbing out the sugar and lemon for the same quantity of thin cut marmalade is not a bad plan in the least.

Mini Vs. Maxi

But should the pudding be large (and potentially look like a baked hat), or should I follow in the steps of Delia Smith and Prue Leith, opting for a daintier duo or quartet of small puddings, individual or to be shared between two? After my first attempt at a large pudding, I decided all subsequent tests should be miniaturized to avoid throwing away the equivalent of my rent in butter.

While I certainly know a few people with pudding molds, I don’t know that I’ve ever even met anyone who owns mini pudding molds (between 180-285ml). Fortunately, they can be MacGuyvered. Just as, in the days before I became the proud owner of a pudding mold, I used a stainless steel bowl with much success, I found 250 mL-capacity wide-mouth jars worked well for mini pudding molds. One must be careful not to overfill, however, as their bounds are quite necessary for containing all of that lovely butter. I learned this on my first mini test, which I pulled from the water bath now quite greasy with a yellow film.

Ultimately, however, I preferred the maxi pudding, mostly for the proportion of crust to filling, but also for its conviviality (sharing!) and commanding presence on the serving platter.

Cooking Methods

Suet puddings are typically steamed, a holdover from the days of their great popularity when most people didn’t have ovens in which to bake puddings. Steamed puddings tend to be rare outside the UK, however, not least because they take hours to cook. During one test I shocked another parent at the park by telling him I’d left a pudding steaming on the stove by its lonesome. I wouldn’t have done it if I did feel totally confident the pot wouldn’t boil dry (and if my toddler wasn’t going to go nuts staying indoors all afternoon)!

I was fascinated to find, however, that lovers of steamed pudding have found all sorts of alternative cooking methods, whether to shorten cook time or to free up a burner. I tried them all… and am afraid I must report that I still prefer to steam! The other methods are all options, however, if you simply cannot abide it.

Oven Steaming: In my experience when hosting a dinner, I’m more likely to lament the lack of oven space than of burners, but perhaps that’s not you. A viable alternative to steaming is cooking the pudding(s) in a water bath in the oven. It does the job at 180°C/350°F in 4 hours (and perhaps you feel better leaving the house with the oven on than with a burner going?). But because the oven doesn’t fill with steam in the same way that a covered, simmering pot does, I found the top got quite crisp and a little tough where it was poking out of the water bath. I’d fill the bath nearly to the rim next time.

Slow Cooker: Placing the pudding(s) in a slow cooker on high filled ¾ up the sides with water is a good trick to free up your entire stove, if indeed you own a slow cooker. The only downside in my opinion was that it took about double the time that it would on the stovetop or in the oven. But if you’d like to get ahead and put your pudding to cook in the morning and forget about it until dinner time (the whole point of a slow cooker, I guess!), this method fits the bill.

Pressure Cooker: We were gifted an Instant Pot by my partner’s uncle at the height of its popularity. After making brown rice in it one time and finding I’d just about saved no time at all faffing around with buttons and instructions, I promptly gave it away. Fortunately, I gave it to my friend downstairs, so I could borrow it back years later for this test. It certainly does the job quickly (if you don’t count reading the instruction manual)! My mini pudding was ready in 35 minutes, which means a full-size pudding would take about an hour. The crust browned admirably but the pastry lid did detach, likely on account of the heightened pressure.

Microwave: I had the least faith in this method and, perhaps unsurprisingly, the least success. Following instructions from (red flag) the comments section of an online newspaper, I covered my mini pudding with plastic wrap instead of the metal lid I’d been using otherwise and cooked it on medium for 5 minutes. Two words: butter everywhere. Reading elsewhere I got the idea this could be mitigated by cooking incrementally—say 1.5 minutes, then a minute’s rest before cooking again, and so on—but I didn’t care enough to try. This might work well for a sponge pudding, but with a pastry base the result was tough. And while I saw my pastry school teachers put stainless steel bowls in the microwave many times (apparently it’s fine as long as they don’t touch the sides), I’ve never been able to bring myself to do it, so testing in my metal pudding mold was out of the question.

A Little Extra Flavour

While I like a piece of Scottish tablet quite a bit, I admit that old fashioned desserts whose main flavors are that of butter and sugar are often not as intriguing to modern palates. For my Sussex Pond Pudding, I decided to add a little intrigue without really modifying the basic structure. I subbed a little rye flour in for some of the all-purpose, upped the average salt measurement, and poured in a few tablespoons of rye whisky to add dimension and amplify the flavor. If you don’t like whisky, you can simply omit it. I used both demerara and light brown sugar for testing, slightly preferring the former. I think a little molasses flavor is nice since there's not a lot going on here.

But is it for everyone?

I ended up photographing my final Sussex Pond Pudding test in my child’s Peter Rabbit bowl because it was just giving such distinct nursery vibes—which I do think have a time and place! On a cold winter’s night, not only is it warming to have something fragrant simmering on the stove for 4 hours, but a heavy, rich dish shot through with pleasantly bitter lemon, is comforting and life-affirming. It definitely needs a bit of cream poured on to help lighten it up a little, a cool contrast to the steaming pudding (which does, by the way, reheat quite well in the microwave).

That said, I think it’s most appealing to people who grew up with it. I’m under no illusions that steaming a pudding for hours at a time is an easy sell.

Similar Vibes..

Test after test, my mind always discreetly trying to think of ways to make the recipe more accessible to most, I began to think of Sussex Pond Pudding as the original self-saucing pudding. You know, those seemingly magical recipes where you pour boiling water over a simple cake batter, which miraculously rises to the top as a thick, sweet, bubbling sauce forms underneath? They should really change their name to pond pudding cakes. In attempt to create something people might be more apt to try, I made two attempts at transforming butterscotch self-saucing pudding into a lemon-scented sibling of Sussex Pond. The scent of it cooking was incredibly similar, and it took only 40 minutes to bake, but I ultimately threw in the towel. The cakes were homely and lacked the insane richness I’d now come to expect from this concept. They lacked the important textural contrast of pastry, lemon chunks and sauce. Plus, if the whole pan wasn’t eaten at once, the cake had a tendency to soak up all the sauce.

Another place my mind was taking me, however, was to one of my favorite American creations, Shaker Lemon Pie—there’s one in my book Jam Bake! A crisp double-crusted pie is filled with sugar-macerated, thinly sliced lemons bound with butter and eggs to create a pudding-like consistency shot through with pleasantly bitter, slightly chewy peel. It’s got the same basic concept, except with more of the best part (the lemon!), only lacking the over-the-top pond aspect. Fortunately, a little toffee sauce took care of that.

The Recipe: Double Rye Sussex Pond Pudding

Serves 4-6

Pastry

150 g all-purpose flour

100 g rye flour

2 tsp sugar

1 ½ tsp baking powder

1 tsp kosher salt

Zest of ½ a lemon

130 g cold brown butter

About 75 g each whole milk and water

Filling

1 large lemon (170 g)

200 g demerara sugar

200 g unsalted butter, cubed

½ tsp flaky salt

2 Tbsp rye whisky

Plus: Cream, for serving

Method

In a medium bowl, combine all-purpose flour, rye flour, sugar, baking powder, salt and lemon zest. Mix well. Use the large holes on a box grater to grate the brown butter into the bowl. Mix to combine then add milk and water, mixing to make a soft (but not sticky) dough. Cut off ¼ of the dough for the lid and reserve.

Transfer the remaining dough to a lightly floured surface, dust with flour, and roll into a round 1 cm thick. Grease a 1.5 L pudding mold (lining the bottom with parchment if you know it to be sticky) and fit in the pastry round.

Cut the ends of the lemon, then cut lengthwise into eighths. Remove any seeds, then cut each piece into 1-inch chunks. In a medium bowl, combine the lemon chunks, sugar, butter and salt. Pack filling into the pastry lined pudding mold and sprinkle the whisky over top.

Roll out the reserved pastry, moisten the edges with cool water, and place over top of filling, pinching the pastry edges together to seal.

Cover, whether with the pudding mold lid or with a layer of baking paper then aluminum foil, and transfer to a large pot with a lid fitted with a rack on the bottom. Add water to come halfway up the side of the pudding mold, then cover and bring to a boil over high heat. Reduce heat to a gentle simmer, and simmer for 4 hours, topping up with boiling water if necessary.

Carefully remove the pudding from the pot, take off the lid, and invert onto a serving plate deep enough to contain a small pond. Serve immediately.

Psst: Want to bake with Camilla?

Camilla's upcoming online workshops will teach you to preserve the bounty of summer fruits both safely and creatively. On March 23rd it's all about pantry powerhouses canned fruits and compotes, while on April 6th she'll teach the art of making lower sugar, no added pectin jam that tastes like FRUIT. For more info, visit camillawynne.com/workshops

Dear Camilla (and Nicola, too, of course!)

Thank you so much for this piece! I will never make it but it was so much fun to read about it (that is, I *will* more than happily eat it if someone else makes it). I was feeling quite depressed (omg, these days the news is awful!) so I turned to something else. You made me laugh out loud! For me, the best part was:

“As a pastry person, I don’t think of myself as ever being squeamish about large quantities of butter and sugar—that’s basically what I’m made of. However, there was something about just cramming a pastry case full of diced butter and sugar that made me just a little skittish. This is a recipe where the gloves come off. There are no niceties. It’s fat and it’s sugar and that’s the joy of it. But I had to learn the hard way.”

I’m English so I love a steamed pudding but I spent many formative years in Vancouver where there is/was an amazing French patisserie called *The Bon Ton*. It was started in 1927 (don’t forget that Vancouver was only established in 1888!) and I knew the ‘daughter-in-law’, who must have been in her 50s when I was a child. She lived to 109 and, when she was 105, was interviewed and asked about her longevity (she was still going into the business and making sure that everything done correctly). She replied that her secret was a life filled with butter and sugar. So, Camilla, you go, girl!

Thank you so much for all your hard work and your humour! I look forward to reading more of your adventures!

I’d like to add, Camilla, that I love how ridiculously stuffed your kitchen is! I thought mine was a nightmare in which to cook — your’s, well, takes the cake! Fabulous.