Kitchen Project #111: Airy Glass Bread (100% Hydration)

The holiest of all breads aka 'Pan de Cristal' or 'glass bread'

Hello,

Welcome to today’s edition of Kitchen Projects. Thank you so much for being here.

I’m so excited about today’s newsletter because I get to dive back into one of my favourite subjects to talk about: BREAD. And not just any bread, the most outrageous of all the holey breads: 100% hydration bread aka ‘glass bread’ or pan de cristal. It’s a feat of dough engineering, honestly.

Over on KP+, I’m sharing a few of my favourite things to eat with this bread inc. crispy courgettes with ricotta, pickled fennel & mortadella sandwiches and the ultimate Pan Con Tomate by Jordon King. Click here to read it.

What’s KP+? Well, it’s the level-up version of this newsletter. By joining KP+, you will support the writing and research that goes into the newsletter (including the commissioning - and fair payment - of all the columnists), join a growing community, access extra content (inc. the full archive) and more. Subscribing is easy and only costs £5 per month. Why not give it a go? Come n join the gang!

Love,

Nicola

Holey Moley! It’s the bread of our dreams!

There are few things I love more than holey bread. I know, I know, we’ve been schooled in the past that it’s not the HOLES that give a loaf worth, but the bread structured AROUND those holes. Though you might think of these as airy breads, I’ve started to think of them as juicy breads, thanks to their unmatchable ability to hold all sorts of toppings. The honeycomb bread network, so tender it borders ontcustardy, acts as a gluten-weaved net, capturing olive oil runoff from pan con tomate or pesto. It acts honourably as a plinth for other superstar ingredients. This, ironically, actually makes it the star of the show.

I’ve been lucky to go to a lot of incredible bakeries and have enjoyed some extraordinary bread courses at fancy restaurants, but my best bread memory is one of the simplest ones.

A few years ago, I stayed in a small village in Southern Spain. The roads were impossibly narrow (we have the bill from SIXT car rental to prove it) and, though it was near a town, the village was sleepy, quiet, remote. But each morning, the collective slumber was broken at 8:30 AM by the sound of a tinny car horn and wheels careering around the treacherous corners with fast-&-furious-level ease. It was a noise we came to love because it was the sound of the baker arriving with a van full of freshly baked bread and pastries from the nearby town.

Each morning we would run downstairs into the streets in our pyjamas and queue up with the Abuelas for our daily bread. You had to be quick - the van driver did not suffer fools (or slow movers) and would drive off as quickly as he arrived if you weren’t careful. This van would arrive three or even four times a day, depending on the day of the week, each time the truck loaded with something slightly different. Our host warned us to avoid the 1pm delivery - never fresh (a fact also confirmed by the lack of wise Abuelas appearing for this van) - but by 3 pm, it was reloaded with newly baked loaves.

The bread, costing around 75 cents, was crispy and airy. We swiped it with garlic and loaded it with supermarket tomatoes, olive oil and vinegar, the holey interior greedily absorbing the melange. We’d sit on the roof terrace with our coffee and inhale the bread enthusiastically. We agreed it was the best thing we’d ever eaten. Five years later, I’m proud to be transporting myself back to that moment as best I can. And I’m so happy to be taking you all with me. I’m confident this is the ultimate late summer bread, perfect for sharing with friends. Pro tip: Invite some friends over + ask them to bring their ultimate holey bread topping. It’s a picnic-tinged potluck of dreams. I did precisely this and shared my dream toppings (along with a guest recipe from the wonderful Jordon) over on KP+:

You’ll know that I have a long love story with high-hydration breads. The 3-day focaccia is probably one of the recipes I see made most often from the newsletter, so it’s natural that this bread would evolve. What does it evolve to, though?

Before we get started… a shout to the authors of Modernist Bread for alerting me to this bread's existence, and for Martin Philip's work on King Arthur Baking who inspired me to give this bread another go! Big thanks.

Water, water, everywhere…

Once you pass floofy focaccia, you start to creep into ciabatta territory. Keep adding water and you’ll find yourself heading into even splashier territory. I’m sure there’s a world of poorly documented high-hydration breads out there, but the Spanish ‘Pan De Cristal’ or ‘glass bread’ is the most well known of these extremely high-hydration breads. Named in the early noughties, it was developed by Jordi Nomen, who now owns his own bakery ‘concept pa’ in Barcelona which specialises in this glassy bread. It is airy, crisp, and ideal for Pan Con Tomate and other Catalan classics.

Characterised by an extremely delicate crumb, it pushes the ciabatta to the absolute limit. Though these breads seem rustic, it may surprise you that these very aerated, high-hydration breads are relatively new inventions.

Ciabatta rose to popularity in the 80s in Italy, created by two bakers to ward off the interloping baguette from the West. So why didn’t these airy breads arrive sooner? To be honest, it probably wasn’t possible. To achieve these extremely hydrated breads, you need very strong flour, which was only accessible thanks to modern wheat production and a thriving trade between countries. Much of this super strong flour can be traced to Canada and Ukraine, which have very hardy wheat with high protein content. The harsher climate - more dramatic winters and summers - is perfect for this variety. You see, many heritage grains, which tend to be softer wheat, simply don’t have the strength to produce extreme crumbs. And for lofty loaves like focaccia, ciabatta or glass bread, we need to turn to hard wheat.

But what about durum wheat? Isn’t that hard wheat grown in Italy? If you’re asking that, the answer is YES. It is a very hard wheat. Although durum wheat is incredibly high in protein, it’s not the ‘right’ protein for making bread. You see, Flour contains proteins - Glutenin and Gliadin - that form gluten bonds in the presence of water. Gluten provides structure, shape and stretch to your dough. The presence of gluten allows the dough to be both elastic (holds its shape) and extensible (stretches). But it’s the particular balance between glutenin and gliadin that makes certain wheat effective for bread making and others not so much.

Durum wheat is high in gliadin but lacks glutenin. Gliadin is effective for extensibility, while glutenin excels in elasticity. This mismatch of skills means Durum wheat has limited use for bread (but makes fantastic for pasta), so it makes sense that the arrival of red wheat, with its ideal combination of proteins, across the world coincided with the (literal) expansion of “local” bread.

Hydration through history

If high-hydration doughs like ciabatta are relatively recent innovations, what was the standard for bread? Standard tin loaves you’ll enjoy today are around 60%-65% a slight increase on the typical 50% in the early 20th and late 19th century. But according to the Modernist Bread books, 19th-century bread was as low as 31% in France. Though we might be used to airy crumbed bread, these are a world away from the more typically dense bread of the past. This, as we’ve discussed, is thanks to modern farming techniques and a global trade market.

So what exactly is high hydration?

You might have run into videos on TikTok or online articles about 100% or 110% hydration bread. But what on earth does that even mean? How is that even possible? We’ve been through this before, but let’s do a little reminder session on baker’s percentages, which is a useful way of denoting and decoding recipes.

Bakers’ percentages refer to the % of an ingredient in proportion to the flour. In a recipe displayed in baker’s percentages, the flour will always be 100%. So, if flour is equal to water, then we say it is ‘100% hydration’.

As we get further into the territory of high-hydration bread, the natural question to ask is… what counts as high hydration? It depends on who you ask, but in my opinion:

55% – 64% - low hydration

65% – 74% - medium hydration

75%+ – high hydration

85%+ - very high hydration

95%+ - are you ok?

So what is the effect? Increasing the hydration results in an ultra-tender crumb that borders on custardy. Beyond 80%, the dough tends to have a free-form shape that needs gentle handling. It has a thin, brittle crust (which can also be a little chewy) that gives way to an irregular structure within. This beautiful structure is a collaborative effort from the yeast and water: The yeast is responsible for expanding the dough with carbon dioxide, which goes into overdrive as it hits the oven, while the water dissolved in the dough turns to steam. This expands the bread. Any thin or weaker spots in the gluten network may be busted open with this rapid expansion leading to irregular holes.

If we’re going by my scale above, today’s bread is in the ‘are you ok’ territory. Making this bread is very easy, but it takes patience and some focused attention to your environment and technique. But I know you can do it.

Building bread formulas

Today we are going to be making ‘lean’ bread. This means it only uses the simplest of ingredients: Flour, water, salt and yeast.

To get started, to make this kind of bread, you need strong, white flour. And I mean strong. If you can find ‘very strong’ bread flour, then you’ll make your life easier. The higher the protein content, the more water your flour can absorb - try adding 100% water to plain flour, and you’ll never achieve flexible greatness. I’ve tested this recipe with 12.5% protein flour (strong) and 14.9% protein flour (very strong), and both worked well. The ‘very strong’ flour allowed me to add up to 110% water, which resulted in an even glassier and custardy crumb. Some brands worked better than others - I have added those to my recipe notes.

Please be under no illusion that this bread is wholesome - it is pure pleasure! So, the most engineered, buff flour you can find will do the trick. If you’re seeking the strongest flour, the one that is in the high 14%s, you can get this from Waitrose (own brand), Matthews or Marriages.

The recipe

Bread recipes are no secret. Most breads share similar parameters for success; within these ‘rules’ we can explore how to build our own recipes. The ingredients are important, but making good bread is all about technique, especially when getting into the upper echelons of hydration. So when it comes to building a bread recipe, the ingredients fall into three categories: Things you can change a lot, things you can change a little, and things you should just leave alone.

Things you can change a lot: The hydration is probably the major defining factor of lean bread. It affects the crumb, the shape and the way you handle the dough. Today’s recipe will incorporate up to 110% hydration, which means 110g of water for every 100g of dough (very strong flour only).

Things you can change a little: Sourdough aside, the amount of yeast we use in a dough is very tactical. As well as this, how we deploy our yeast (through a preferment or directly into the dough) will make a difference in how the dough handles and bakes.

Things you just leave alone: The amount of salt in the dough tends to be pretty standard, around 2%. Salt has a role in controlling fermentation. Too much salt and it’ll dehydrate the yeast. Not enough, and the bread is hideously tasteless.

And beyond that, it’s all down to technique. Shall we dive in?

The Role of Yeast

When you add yeast to a mixture of flour and water, the dough rises and becomes filled with bubbles. This is known as fermentation. If you increase the temperature, the yeast activity ticks up, and fermentation speeds up.

Fermentation happens because yeast is a hungry, active microbe. It guzzles its way through the flour, breaks down the sugars and starch and produces CO2 as a by-product. This gas is captured by the gluten network, which causes the dough to rise. If the gluten is not developed, then there is nothing to capture the gas. A bread dough without strength is a sticky mess - the flour is fermented (“eaten”) and completely slack.

This is why the number one objective is to balance fermentation with gluten development.

To achieve this, we need to pay attention to the amount of yeast we introduce into a recipe. Commercial yeast is incredibly fervent, a single strain of yeast that has been isolated, laboratory grown and tailored over the years to be extremely efficient in raising bread. This means that dry yeast, compared to wild yeasts in sourdough, has a reasonably quick fermentation cycle. Using a relatively large amount of yeast means it would quickly eat through the dough. This will result in an underdeveloped crumb structure and overfed and exhausted yeasts by the time it gets to the oven.

Lowering the amount of yeast gives us more time to build structure and work with the gluten development of the dough. So, for incredibly hydrated doughs where the flour is already well diluted in water, reducing the yeast to lower than 0.75% of the flour weight is sensible to give yourself a better chance of developing the gluten.

So what is the right amount of yeast? The quantity will massively depend on the quality of your flour and your environment. In a cooler environment with very strong flour, or if you are using a mixer which means we get the gluten developed about five times quicker than doing it by hand, I’d suggest 0.75% flour. In a warmer environment, I’d suggest halving this to about 0.4% flour to give yourself the best chance of success.

Building strength

Anyone with a stand mixer may be happy to hear that making this bread is incredibly easy. With a bit of patience, a high-hydration dough does come together quite easily in a mixer. After this, we gently stretch the dough as it ferments to build further strength on this incredible head start given by the mixer. You can achieve great results by hand, but it is a little more hands-on; Rather than mixing the dough to full development right at the beginning of the process, you slowly add strength with a series of bowl mixes, stretches, and folds.

Learning to speak bread + what to do when it isn’t behaving

When you make bread, you must learn to become intuitive about the stage your bread is at since our environments are different. You're in trouble if you get to the stage where your dough is super active, but you’ve got zero gluten development. The dough will feel sticky and have very little structure - it will tear if you try and work with it. If baked, this bread will fall flat in the oven since there is no structure to capture the steam or gases released in the baking process.

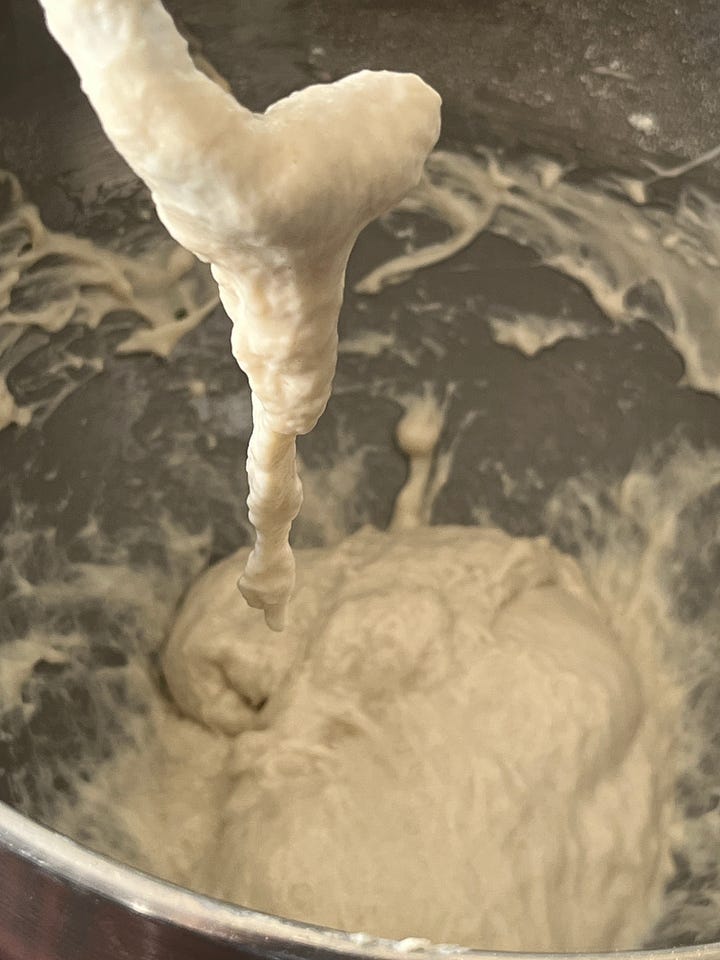

The best way to test gluten development is simply by stretching the dough. If it stretches a little without tearing but doesn't stretch very thin, then you are on your way to gluten development.

If you can perform the 'window pane' test (you can stretch it thin enough to see light through it, and it doesn't look like it's tearing at all), then you have achieved full gluten development This means you have a network that can hold all the gasses as well as being strong enough to withstand higher levels of hydration.

If you find yourself in a situation where you’ve been working on your dough, but it has no strength, get it in the fridge IMMEDIATELY. Remember, the only thing that really impacts the fermentation rate is temperature. While you’ll often hear recipes ask you to put your dough somewhere warm to help it rise, you can also go the other way. Cooling the bread down will calm the yeast activity and give you a better chance of developing gluten before it is too late. Just take it out of the fridge to perform your turns to build the gluten. Once it has strength, you can continue fermenting the dough.

But WHY does water make bread harder to work with? When you increase the hydration of your dough, you are diluting the gluten network. This has a weakening effect. Before the gluten network has developed, the dough will not be cohesive - it will tear if you try and move it. Since the dough is literally wetter, it is also sticky, making it hard to handle.

Finding the ultimate mixing and baking technique.

Working with high-hydration doughs, especially without a mixer, is no easy feat. So this week, I thought about the best way to mix this for 1) best results and 2) simplicity. And was there a way to sneak more water in there? From preferments to tangzhongs to autolyse, I wanted to compare to the standard all-in-one method (mix all the ingredients, add folds, ferment, bake!), so I gave it a go. Let’s dive in.

Test 1: Prolonged autolyse

As soon as you add water to flour, it hydrates the proteins, forming gluten bonds. Autolyse is when you mix your flour and water together and leave it alone to absorb fully.

Theory: The dough will be easier to work if it goes through a long autolyse period before adding the yeast, giving a huge head start to gluten development.

The test: To test this, I mixed flour and water and left for an hour before adding the yeast and salt.

The result: The dough was a bit easier to handle at first but not significantly for the extra steps - because the yeast isn’t added until an hour into the process, it just unnecessarily prolongs the process. The final crumb was not significantly different. Not really worth it

Test 2: Preferments

A pre-ferment is a mixture of flour/liquid/yeast from your recipe that you mix ahead of time. There are many names for pre-ferments - bigas, poolish, sponge, pate fermentee. There are two that I tend toward: The Biga and Poolish. The only difference is the amount of water. Biga tends to be drier (50% hydration), while Poolish is wet (100% hydration)

Biga is typically used in Italy and is the foundation for Neapolitan-style pizzas and ciabattas. It tends to have a lower amount of yeast and a longer fermentation time (at least 12h but up to 3-4 days in the fridge), while Poolish can be mixed 3-4 hours before baking. The acidity of these preferments bolsters gluten development, speeding up the process as well as adding much welcome flavour. 100% bread is great but isn’t the most complex in flavour. Preferments can help with that!

Theory: Bread made with preferments will have a headstart on gluten development and will be more flavourful.

The test: I mixed two doughs, one with a poolish base and one with a biga base.

The result: The already wet poolish was a total FLOP. I tried it twice (just in case I was imagining things), and I found the dough fermented way too quickly and was an utter mess. The biga, however, made a incredibly easy dough to work with and came together beautifully. It had a lot of strength and a more pronounced flavour. The structure of the dough was less erratic than the all-in-one dough. If you have time, I recommend the biga method 100% because the dough was SO easy to work with - and its overall yeast % is only 0.2%! If you want to know how to do it, comment on this week’s KP+ and I’ll share the recipe.

Test 3: What about Tangzhongs

‘Tangzhong’ is when we cook a portion of a recipe’s flour and water until it thickens (gelatinising it) before adding to the other ingredients’. The tangzhong technique was pioneered by Yvonne Chen in the 1990s in her book ‘The 65-degree bread doctor’. Here she found that using this technique could introduce a higher proportion of hydration into bakes. By pre-cooking the flour, we are essentially ‘trapping’ hydration by keeping moisture busy with starch, effectively binding the water. This means we can add more hydration whilst keeping the bread stable, as well as having the effect of improving oven spring and texture.

The smart idea of trying a tangzhong in this 100% bread was recommended by Teresa Müller on Instagram! Thank you, Teresa :)

Theory: By precooking some of the flour with water, we can sneak more hydration, making the dough easier to work with.

Test: I cooked 20g flour with 100g water, then added this to another 100g flour and 20g fresh water giving me a 100% dough

Result: Intriguingly, this technique did not work out as expected. The dough barely built any strength after 40 minutes of mixing in a stand mixer. I left it to ferment anyway and shaped and baked it - it rose to the occasion but was still relatively small compared to other tests. The structure was very bubbly, and the interior was incredibly moist, thanks to the tangzhong technique. Though it was an interesting experiment, I can’t recommend it for this type of bread. Though gelatinisation is great for squishy bread, heating the flour somewhat restricts its ability to form gluten bonds, which is essential for very hydrated bread.

Test 4: Adding folds

When I worked at a sourdough bakery, we fully developed our doughs in the mixer before transferring them into containers (in a warm room) for the bulk fermentation process. As the dough fermented, we would go in regularly to stretch and fold the dough. So, for the mixer version of this recipe where we develop the dough to full development in a stand mixer, I wanted to know if there was any benefit in adding additional folds during the bulk ferment process. Surely if the gluten was already developed… more folds can’t do *that* much?

Test: I mixed two doughs to full development in a mixer and then bulk-fermented them separately. I added folds to one and left the other one completely alone. I shaped and baked at the same time.

Result: The dough with folds expanded more in the oven and had more overall volume and structure. Definitely worth doing - not much extra work and much better bread overall. The folding process further strengthens the dough and reorganises the bubble structure. Admittedly, the dough without any extra folds was a bit wilder with larger bubbles but overall diminished from the lack of extra strength.

Test 5: Cold fermentation

Cold fermentation is a technique that we can apply to any dough. After the yeast is established, we can move the dough into the fridge and slow the yeast activity right down. When the yeast isn’t going absolutely nuts digesting sugar and producing CO2, it is really helpful in a flavour-creating process called the… wait for it… Alpha Amylase Reaction.

It’s not a catchy name, and you don’t need to remember it - all you need to know is that it’s an action where complex starches are further broken down into sugars, and flavours are made. Although this does happen if you just left flour and water on its own, yeast - when under control in a cold environment - can provide some useful enzyme action to coax those flavours out and offer new dimensions to your bread.

Result: Absolute flop. This dough is so sensitive to over-fermenting that even a cold fermentation is risky. That, or my fridge wasn’t cold enough. It had the most open wacky crumb, but it was incredibly flat. Not worth the extra time. If you’re going to spend any extra time on this bread, I'd spend it on a preferment rather than fermenting the entire dough.

The final proof

Once your gluten has developed and your bread is nicely fermented, it’s time to divide the bread. But should we proof it again before baking, or should we just bake it right away? I decided to find out.

The test: I halved a dough and left one to proof for one hour while I immediately baked the other.

Results: Both breads had fantastic interiors, but the volume on the proofed dough was much better. Pushing the proof for the final time was worth it, but if you are in a rush, you can go straight into the oven.

The bake

So, you’ve spent all this time making your dough and reached the point of pure puffy fluff. Now there’s just one last hurdle: The bake! This bread likes to be baked hot - you want to convert all that water into steam as quickly as possible. In addition, a steamy oven will help expansion by keeping the crust supple as it opens. I’ve shared a few steam tactics in the method. Loaves baked without steam may bust open as they bake and have a much thicker crust.

Because there is so much water in the bread, you do need to bake it for quite a long time on high heat. Otherwise, the interior will not be fully cooked. If you prefer less colour on the bread, add foil halfway through baking to prevent it from colouring as extremely in the last part of the bake. I personally LOVE a dark crust, though.

If you have a baking stone, I’d suggest using it. If you don’t, pre-heat a flat tray (or an upside-down tray, so you don’t have the lip in the way of sliding it in) to give the base of your bread the best chance of baking.

I tested a few methods, but preheating the oven to 250c fan, and then reducing it immediately to 200c worked well for me. After 20 minutes, I remove the steam source and bake for another 10 minutes. After that, I flip the bread over carefully and brown the base for another 5-10. Once removed from the oven, leave it to cool for 30 minutes before cracking in.

Alright, let’s make it.

100% hydration bread “glass bread”

The success of the bread is linked to the flour that you use. I had very good results with the Waitrose strong flours, and good results with Allison’s Bread Flour and Dove’s Strong Flour Any artisanal flour labelled ‘ciabatta’ flour should work well too. If you can find ‘very strong’ or Canadian flour, you’ll have a much easier time making this recipe. If you’re in the US, Martin Phillip developed a recipe using KA Bread flour, so I’m sure that’ll work great.

Please note, if you are new to making very wet, doughs, i’d suggest starting this recipe by trying 90% hydration (360g water per 400g flour)

100% dough - by hand

400g strong bread flour (over 12.5%)

400g Water

1.5-2g Dry yeast (about ½-2/3rd tsp)*

8g Fine Salt

*For the by-hand version of this recipe, we are reducing the yeast to approx 0.4% of the flour weight so we have more time to develop the gluten before fermentation takes over. If it is very cold where you are, you can increase this very slightly. The important thing is to keep it low!

Notes: Once you’ve made this bread a few times, you can introduce an additional 20-40g Water as directed in the recipe (optional, only for very strong flour 14%+)

100% dough - mixer

400g strong bread flour (over 12.5%)

400g Water

40g Water (optional)

3g Dry yeast

8g Fine Salt

*For the mixer version of this, we can increase the yeast because we are developing the gluten in the mixer and we don’t need the extra time to develop it before fermentation takes place. This is equal to 0.75% of the flour weight.

Directions by hand

Mix all the ingredients together. Cover and leave for 30 mins.

Wet hands then lift and stretch the dough 8-10 times to help develop the gluten.

Cover and rest for 15 minutes. Repeat the stretch and fold. Cover and rest for 15 minutes. Repeat the stretch and fold. Cover and rest for 15 minutes. Repeat the stretch and fold. Add a little olive oil around the edge of the bowl and help nudge it in with your hands. Cover and rest for 15 mins.

Wet hands and perform a coil foil. This is when you lift the dough up from the middle and place it back down on itself. You can repeat this as many times as possible to help build strength in the dough. Cover and rest for 30 mins.

Wet hands and perform a coil foil. This is when you lift the dough up from the middle and place it back down on itself. You can repeat this as many times as possible to help build strength in the dough.Cover and rest for 30 mins.

At this point, the dough should be much stronger. If it doesn’t “window pane” then perform another coil fold and rest for another 30 minutes before checking again.

Once it has reached the window pane stage, leave to get super puffy for about 1.5-2hr. The dough will wobble a lot when you move the bowl and be at least twice as big as when you started mixing it.

Directions in mixer

Add all the ingredients into the mixer. Mix with paddle on medium speed for 2 mins. Change to Hook and mix for 3 mins.

Rest the dough for 3 mins then mix on medium high speed for 3 mins.

If using the extra water, add half then mix the dough for 5 mins on medium high speed then rest for 3 minutes.

Add the rest of the water, if using, then mix on high speed for 5 mins. At this point the dough should be fully developed and smooth and can be pulled into a thin windowpane. If not, continue resting and mixing in a similar schedule to the above.

Move into a lightly oiled bowl. Rest for 1 hour then perform a coil fold. 1h rest (10:30)

Perform a coil fold. Rest for 30 minutes. Perform another coil fold then rest for 30 minutes. Perform one more coil fold then rest for 1.5-2 hour until very very puffy.

Shaping and baking

Heavily flour a clean kitchen worktop and flour the top of the bread. Use a dough scraper to release the dough from the sides of the bowl then carefully tip it onto the floured worktop. It will be so puffy and aerated. You need to treat it gently. I like to give it a little bit of a tidy up by gently pulling the skin of an edge to cover any flabby bits - this tightens up the shape slightly. Flour the top and then divide as desired. I prefer two larger loaves, but you could split into 3 or 4. You could even bake it as one large loaf.

Prepare greaseproof paper cut into squares / rectangles large enough to home your dough. Flour your hands then gently, with the help of a dough scraper if you like, pick the dough up and place it on the paper. The key here is to be confident and to use as much flour as you need!

Leave the dough to proof for 1 hour. It will spread out a little and be very wobbly and flubby.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 250c fan with a baking stone or flat tray in the oven if you have one, along with a small heatproof dish (I use a enamel dish) which we will add ice into.

To prepare a steam tray, roll up a kitchen towel and put it into a small tray and set aside on your kitchen counter. When you are ready to bake, boil some water and pour onto the towel. It should absorb well. Put this into the oven.

To load your breads into the oven, move your breads carefully onto a flat tray or chopping board. Slide the breads, on their paper, into the oven. Add ice to the pre-heated tray then shut the door.

Turn the oven down to 200c fan. After 20 minutes, remove the steam sources. Bake for a further 10 minutes. After this, I like to turn the bread over carefully and brown the bases a little more, but this isn’t essential.

Leave to cool on a rack for 30 minutes - 1h. Enjoy! The bread will get chewy and soft after a while at room temp, but slice in half and toast.

For a few of my favourite ways to enjoy this bread, check out this week’s KP+, ft. courgettes & ricotta, pan con tomate by Jordon King and a mortadella sandwich with a quick pickle.

yummmmmmm!!!!!! Def need to make this...

Omg I can’t wait to make this!! Is this bread okay the next day? I’m having people over for dinner on Tuesday and wondering if it’ll still be good if I make it on Monday?